Brunch with the Post

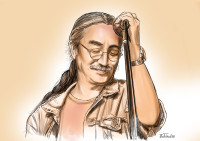

Ghanshyam Bhusal: The prime minister needs to realise his style is not working

The Nepal Communist Party ideologue evaluates his party’s performance in government and talks about the relevance of Marxism today.

Pranaya SJB Rana

It’s been over a year and a half since the government of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli came to power—the first government in the history of modern Nepal to have a comfortable two-thirds majority in Parliament, especially after the merger of Oli’s CPN-UML party with the Maoist party of Pushpa Kamal Dahal. After decades of political instability, here was a government that had a clear and stable mandate for the next five years. This stability had given people hope, but so far, little has come of it.

Unpopular bills and attempts to stifle dissent both in government and within the ruling Nepal Communist Party have been roundly criticised by the breadth of the political spectrum, from the opposition Nepali Congress to dissenting leaders within the ruling party itself. Ghanshyam Bhusal has often been at the forefront of the internal criticism, not afraid to speak out against the strongman tactics of his party co-chairs. So when we meet at the Bricks Cafe in Kupondole, naturally, the first question I ask him is how he evaluates his party’s year-and-a-half in office.

Bhusal is circumspect, but not overtly critical.

“Let’s look at both what happened and what didn’t happen,” he says. “We made laws as directed by the constitution, and our foreign relations are balanced, especially when we look at them in comparison to previous administrations. Of course, a small country like ours could always do better but the country's agendas are on the right track. There are also more activities at the local level, especially with regards to roads, water, electricity. I believe that the people feel that there is a government all the way down to the lowest level.”

Bhusal calls these positives, but not everyone would agree. This government’s laws have been heavily criticised. The Guthi Bill saw one of the largest ever public turnouts in recent history against an unpopular law. The Media Council Bill has been opposed by the media fraternity for attempting to impose restrictions on freedom of the press, and many see the IT Bill too as an attempt to curtail freedom of expression.

Bhusal sees negatives, too.

“The government has focused on large projects, dream projects that have been promised to the people. I believe that focus wasn’t prudent and those projects aren’t possible,” he says matter-of-factly. “We’re too focused on ships and railways.”

Bhusal is an old political hand, part of what has been called the ‘third current’ within the former UML that sought to reorient that party’s ideology away from the dogma of Marxism-Leninism and towards a more contemporary Marxism, one that takes into account Nepal’s evolution from a largely feudal society into a capitalist one. Bhusal is the consummate communist—academic, intellectual and prone to wearing drab grey clothing.

But Bhusal is not a young man anymore. His triglycerides are high and he orders himself smoked chicken pasta with a black tea to start. He’s been working out and running on a treadmill at home. And his criticism, while vocal, is no longer fiery; it is rather academic.

While many might call Nepal a crony capitalist state, Bhusal prefers to call the current political economy ‘comprador capitalism’ (or in Nepali, dalal punjibad), a slight variance in terms. Comprador capitalism is largely Latin American in origin and it identifies a kind of capitalism that acts on behalf of others, primarily foreign interests, whether they be political or capitalist. Crony capitalism, on the other hand, is more about ruling elites and their nexus with the political class.

“Many of our leaders still believe that we are a feudal society but we’ve already become capitalist. This is what Chaitanya Mishra has also been saying,” he says. “We are a capitalist society but what kind of capitalist society? There are two types of capitalist societies—one is a dependent capitalism that does not create any employment, it simply does trade and business; the other is a productive, nationalist capitalism that creates jobs.”

According to Bhusal, comprador capitalism first destroys governance by facilitating corruption. Then, it infiltrates the political parties and buys the security forces so that it can punish those that are against its interests. After that, it finds judges that it can put into pocket so the judiciary can make decisions on its behalf. In this way, he says, it completely captures the state machinery.

“The first step towards turning this comprador capitalism into a natonalist productive capitalism is to recognise that we are a capitalist society,” Bhusal says. “This is the point that all the Maoists, including [Mohan] Baidya and [Netra Bikram Chand] Biplab, have come to, but one that Oli still hasn’t recognised.”

Perhaps many in the ruling party don’t recognise this because they don’t want to, as they themselves have been coopted by the kind of comprador capitalism that Bhusal is alluding to. Bishnu Poudel, party general secretary, has been implicated in the Baluwatar land scam and Bhusal says that the matter should be discussed openly in the party, instead of pretending like nothing is the matter.

“Everyone says there’s corruption in the bureaucracy but that’s a few rupees here and a few rupees there,” he says. “Large-scale corruption is happening in politics, corruption in the millions. A good party will put an end to this. If a party wants to get rid of corruption, then it needs to start with itself.”

The Nepal Communist Party, the largest ever communist force in the country’s history, is a behemoth, the combination of the two largest parties in the country. It has combined the UML’s organisational strength with the Maoists’ once-progressive ideological bent. Or so it would seem on paper. But the party does not appear united. Even to an outsider, there are fissures throughout the party, especially when it comes to the top leadership of Pushpa Kamal Dahal and KP Sharma Oli.

“The two co-chairs have come to believe that party unity happened because of their prudence and their far-sightedness. They believe that they played a historic role in this historic unity,” says Bhusal. “But the party does not see it that way, and neither do the people.”

Bhusal says there’s a growing voice within the party that wants the group to move ahead collectively, both in the party and in government. “But the problem is that the two leaders are more concerned with each other,” he says, “rather than the party as a whole.”

So is it true that the Oli and Dahal don’t trust each other, I ask.

“Yes, and I don’t see any basis for them to trust each other,” he replies. “Trust requires a shared agenda or a shared principle, which they don’t have.”

Nepali politics can be Byzantine in its workings, where political leaders are constantly maneuvering to outplay each other. Dahal has long felt slighted by Oli, who has dominated both government and party. A few months ago, Dahal brought up a gentleman’s agreement between the two, which had said that the two co-chairs would split the party’s governmental mandate. Then, all seemed well when Oli and Dahal came together to appoint leadership to the party’s various departments and elevated Bamdev Gautam to vice-chair. But when Oli was most recently in Singapore for medical treatment, Dahal was making moves, meeting leaders and ministers.

All of this has largely to do with the prime minister. Many party insiders say that Oli works alone, surrounded by a close coterie of advisors. He rarely consults with his party and takes decisions unilaterally.

“Oli wants to act like an American president, where he doesn’t need the permission of the party to do anything,” says Bhusal. “But we function in the British style where the prime minister is beholden to the party and if he does something wrong, then the party can recall him.”

Bhusal said Oli’s style of approaching things single-handedly in the past year-and-a-half shows that his style of governance has largely failed.

When it comes to his health, Oli is not well, no matter how much bravado he might try to project through teleconferences from Singapore. He’s had his kidney replaced and there are rumours he might need another transplant. But he has refused to budge, showing no signs of letting Dahal or anyone else take over, whether in party or in government.

But Bhusal is optimistic.

“Oli needs to realise that his style is not working. And given his history and the burden of responsibility he shoulders, I am hopeful that he will realise it,” he says.

Much remains to be done, within the party and in government. More than three years remain in the party’s mandate but the party itself needs to complete its unification. Leaders, particularly Madhav Kumar Nepal, are disgruntled and even the rank-and-file is not happy.

And amidst all this, Dahal and Oli have consistently made ominous remarks, pointing to vague “threats” and “dangers” to the current republican order. I ask Bhusal if there is any substance to this.

“The old guard will always pose a threat, even if it can never return fully. It might disturb or attempt to derail the new system,” he says. “The only real threat can arise if either the Communists or the Congress decides to backtrack as these were the primary forces of the new changes. I don’t see that happening anytime soon.”

Maybe Oli and Dahal both want to remind us of what is at stake, he says. But are they? Our political leaders have always been more Machiavellian than we realise.

We’ve finished our meals and over black coffee, we start venturing into how Marx’s alienation could apply to someone who works away from home in Gulf. Bhusal believes that the truly alienated are those who are at home, not working but receiving remittances. But that is a conversation for another day.

I ask him about the relevance of Marxism today, when the world has gone capitalist and many consider Nepal’s political parties as post-political, or even neoliberal. But Bhusal, despite his elevated triglycerides, believes Marxism can still provide a critical way of looking at society.

“As a method, Marxism is as relevant as ever. It is a multidimensional lens through which we can look at society,” says Bhusal. “Marxism is not a dogma, it needs evolution and change.”

ON THE MENU

Bricks Cafe, Kupondole

Americano X2: Rs 260

Mineral Water: Rs 130

Cappuccino: Rs 180

Black Tea: Rs 75

Grilled Fish: Rs 650

Smoked Chicken Pasta X2: Rs 980

8.79°C Kathmandu

8.79°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)