Books

A house divided

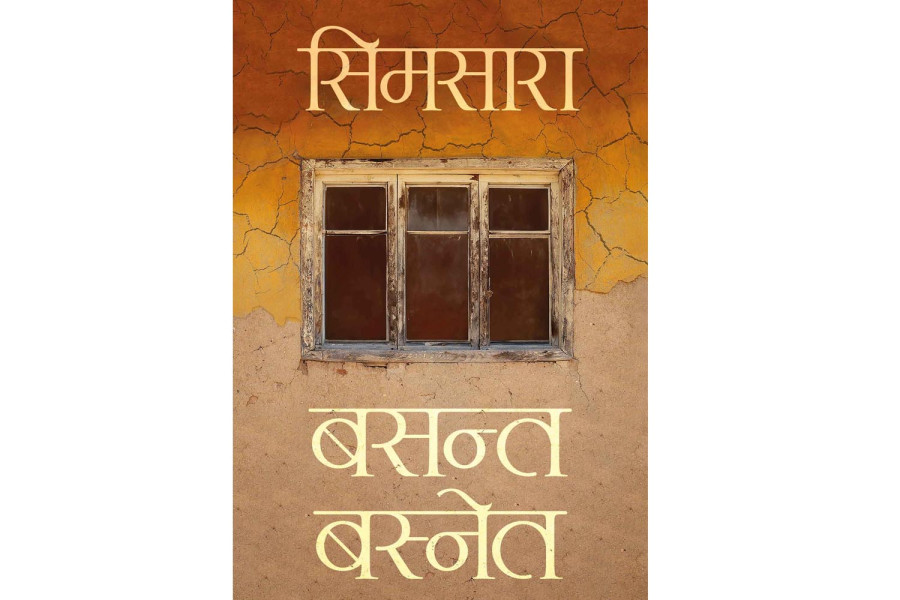

A family’s unravelling told through a teenage son’s eyes, Basanta Basnet’s ‘Simsara’ is a haunting tale of love, loss, and resilience.

Deepak Adhikari

Leo Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’, a romantic tragedy set in 19th-century tsarist Russia, opens with a timeless declaration: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” This sentiment encapsulates the central theme of Basanta Basnet’s Nepali novel, ‘Simsara’, which explores the emotional turmoil of a dysfunctional family in Nepal’s eastern hills.

Set in the misty mountain village of Khawa in an unnamed eastern district (possibly Panchthar or Ilam), ‘Simsara’ revolves around a troubled household. The father, Dhanrup, a postman nearing retirement, is often absent from their newly built home near a graveyard. His wife, Mandakranta, an unlettered yet formidable woman, shoulders the family’s burdens. Their son, 13-year-old Sambat, narrates the story, grappling with his parents’ growing estrangement and his father’s emotional detachment and eventual abandonment.

As Dhanrup drifts away physically and emotionally, he becomes involved with Chhaya Devi, a woman half his age. Meanwhile, Sambat harbours feelings for Iswi, who, in a twist of fate, turns out to be his stepmother’s younger sister. Basnet weaves a narrative rich with themes of infidelity, longing, and familial discord.

Family sagas have been a staple of the novel genre since its emergence in the 18th century, coinciding with the rise of the middle class in Europe. The novel’s expansive form allows for deep psychological exploration and socio-political commentary, making it a dominant literary genre even in the 21st century.

In ‘Simsara’, Basnet deftly unpacks the layered tensions within a fractured household. Mandakranta, estranged from her husband, seeks both love and justice. She turns to the Maoist rebels’ kangaroo courts and later to the government’s legal system. When the court official visits her, she offers him a delicious local chicken curry. Meanwhile, Sambat, caught in the family tragedy, is a teenager torn between confusion and anger. He, however, has fleeting moments of tenderness—particularly towards Iswi, a symbol of hope that ultimately fades.

Sambat and Mandakranta emerge as compelling characters, while Dhanrup typifies the archetypal Nepali man who shirks domestic responsibilities under the guise of being a breadwinner. Sambat’s internal turmoil—his lost childhood, his liminal state between boyhood and adulthood—is portrayed with emotional intensity, evoking readers’ empathy. Yet, the author allows him to use complex, philosophical musings, which feels incongruous for a school-going teenager.

Basnet’s linguistic dexterity is evident throughout the novel as he plays with words to uncover deeper meanings. However, his stylistic flourishes can sometimes feel excessive and repetitive.

Some transitions in the narrative, such as Sambat’s turning to alcohol, feel abrupt. In addition to Sambat, the novel also voices Dhanrup and an unexpected narrator—a wooden pillar (Khamboko Bayan). The pillar bears silent witness to the family’s rise and fall. This creative storytelling device, while innovative, sometimes blurs narrative clarity, making it difficult to distinguish the pillar’s voice from Sambat’s. Nevertheless, it suggests that there are multiple truths even within a house.

The novel is rich with marginal characters who play significant roles in helping troubled families navigate complex and turbulent society. Among them is the jogi (ascetic), who follows an ancient tradition of visiting houses at night, blowing an antelope horn to ward off evil spirits. Another is Pandit (described as Bhimkaya for his burly figure), who performs a Puja at Mandakranta’s request to protect the house from misfortune.

They all suggest the house was improperly built, with major flaws in its foundation that were overlooked during the design process. As a result, misery has plagued the family, giving rise to its haunted reputation. The author deepens this eerie atmosphere through chilling descriptions and the haunting presence of the nearby cemetery, reinforcing a sense of gloom. The narrative also explores the contrast between a house and a home, echoing the adage: “Home is where the heart is.” The house becomes a powerful metaphor for their circumstances, much like the marriage itself.

Compared to his debut novel, ‘Mahabhara’, which tackles broader themes of religion, the Maoist insurgency, and love, ‘Simsara’ is a tightly woven domestic drama. Growing up in Phidim, the district headquarters of Panchthar, I found the novel’s rural setting intimately familiar, much like ‘Mahabhara’, which evoked my childhood memories of Dhan Nach, Palam, and Melas.

While reading ‘Simsara’, BP Koirala’s ‘Babu Aama Ra Chhora’ came to mind. Set in the 1960s, it explores a love triangle in which a son’s lover ultimately marries his father. While Koirala introduced psychoanalysis in Nepali fiction, drawing a direct parallel between his work and Basnet’s would be a stretch. However, both authors share a common strength: portraying strong female characters. With Mandakranta as the unwavering pillar of a crumbling household, Basnet crafts a powerful narrative of female resilience in ‘Simsara’.

The book succeeds in its primary aim of creating a compelling portrait of a family in crisis. Through Mandakranta’s unwavering pursuit of justice and eventual forgiveness of her sauta (her husband's second wife), Sambat’s loss of innocence, and Dhanrup’s emotional isolation, Basnet reveals the intricate connection between personal struggles and societal dynamics in modern Nepal.

While not without its flaws, ‘Simsara’ is a valuable contribution to Nepali literature. It offers a riveting narrative of family dynamics that resonates well beyond its cultural context.

Adhikari is a freelance journalist based in Kathmandu.

___

Simsara

Author: Basanta Basnet

Publisher: FinePrint

Year: 2024

21.13°C Kathmandu

21.13°C Kathmandu