Books

Home and the world

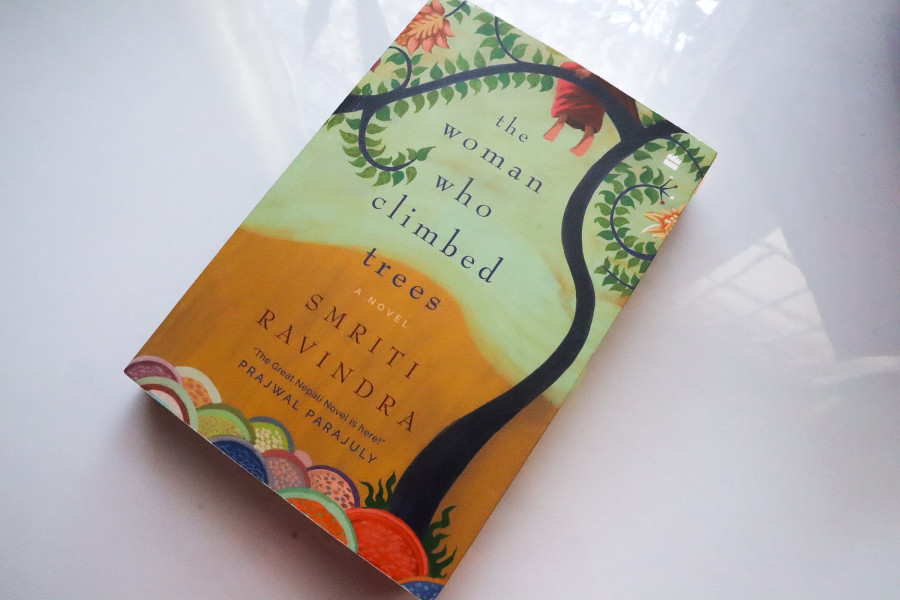

Smriti Ravindra’s debut novel explores a woman’s tumultuous journey between her inner self and an outer world in search of a home.

Deepali Shrestha

As a child, when I heard stories from my mother and grandmothers about their marriage, I would ask how somebody could easily leave their home and live with strangers. It was as if the concept of a home always eluded women in my family. Today, as I have grown into a woman, I have patiently peeled various layers of the question and perhaps reached its core: More than how they do it, it is about what it means. Knowing what home means to a woman is at the heart of ‘The Woman Who Climbed Trees’, Smriti Ravindra’s debut novel, which recently won the 2023 TATA Literature Live awards for First Book.

The novel plunges into the vast sea of womanhood and sheds light on the story of Meena and her daughter, Preeti, who are making sense of the placelessness they find themselves in: The former in her traditional marriage and the latter in her coming-of-age. The essence of mother and motherland to a woman is best explained by a woman applying mehandi on Meena’s hands at her wedding: “They are impermanent dreams.”

At 14, Meena marries Manmohan and leaves her family in Darbhanga, Bihar, for a place similar yet different in many ways from her home. In Sabaila, Janakpur, she despises her lonely marital life in the presence of her stout, not-so-motherly mother-in-law. Manmohan, who goes to Kathmandu for work, cannot fulfil her longing for a loving companion. He feels the sentiments of oppressed Madheshis and is keen to fulfil his political ambitions, but he has no time to think about his wife’s feelings. At best, he is a ceremonial husband in a traditional marriage reeking with patriarchy. Meanwhile, what keeps Meena going is a special bond with Kumud, her sister-in-law. Kumud provides Meena with a sense of love and tenderness, but this bond, too, is broken after Manmohan takes Meena to Kathmandu.

Between Kathmandu’s hills, temples, stupas, fables and the watchful eyes of the late 20th-century kingdom, Meena is alone even with Manmohan under the same roof. When she visits Darbhanga during her pregnancy, the pictures of Krishna, Ganesh and other deities in her room fail to guard her against subsequent miscarriages. “My body is a graveyard,” Meena once tells her daughter, Preeti, recounting the foetuses she lost.

Preeti’s first-person narrative occupies much of the book’s eight parts. Preeti’s relationship with her friend Sachi and her longings mirror what Meena feels for Kumud, depicting their intense sexual and emotional yearning for their female companions. The story captures the different shades of female sexuality and friendship, exploring female pleasure and homoeroticism, where women and young girls secretly fulfil their desires and uncover warmth within one another’s touch. “Girls always love girls before they love anyone else, isn’t it true?” Meena asks Preeti.

Ravindra’s writing is simple yet elegant, without any literary complexities left for readers to ponder. Although her prose is straightforward and seamless, there are surprises between the lines, making you stop and admire the beauty of her imagination. “Home had taken on wheels and was about to roll away,” says Preeti when Meena is about to leave for Darbhanga. Ravindra’s literary flair is also evident when Kaveri tells Meena, “A bride’s mehendi is how her mother’s house sits within the bride’s heart, first burning inside her, then lingering as a memory.” The beginning does a satisfactory job of portraying the nitty-gritty of village life and Meena’s early marital years, but the plot progressively metamorphoses with Preeti’s perspective. When Meena’s mental health starts crumbling, Ravindra’s prose and imagination become vibrant, gripping the readers with every page.

Folklore and myths have always been an indispensable part of oral storytelling in South Asian families for generations. Kathmandu and Janakpur, being ancient cities with abundant monumental art, encompass rich myths connected to almost every historical element. Whether it be the tales of the barber’s wife, Manmohan’s babysitter, or Kaveri, Meena’s mother, folklore and myths embellish the story, incorporating a jarring predictability and foreshadowing. They add an extra layer to the character’s inner world, connecting them with a fibre, transcending time, borders and generations.

The deep scars inflicted upon one’s psychology through discrimination, borderland issues and separation are lucidly expressed in the novel. In the capital, the family experiences frequent situations where they are seen more as an Indian than a Nepali just because they are Madheshis. Derogatory terms towards these communities slip from people’s mouths through microaggression. After India’s economic blockade during 1989-90, a boiling resentment towards the country landed on Kathmandu’s streets, making such offensive terms ubiquitous. This issue is also relevant today as many Madheshis still feel discriminated against by other ethnicities and through policies. Portraying such complexities is deeply personal to Ravindra, a Madhesi Nepali woman who spent much of her formative years in Kathmandu. Through the story—primarily from Preeti’s experience—an evocation unfolds, making us deeply empathise with her circumstances.

Ravindra has dedicated a significant amount of pages to portraying the vignettes of women’s mental health and psychology in a society that prioritises men’s needs, especially in marital roles. The female characters’ affinity towards “madness” reveals the disturbing yet honest reality of the women in patriarchy’s shackles. Madness results as a by-product in women who aren't allowed to have a mind. “She was not mad, though she longed for madness,” reads one of the lines describing Meena.

‘The Woman Who Climbed Trees’ symbolises trees as a place akin to a home for the women who release themselves, unbothered by societal norms, amid misery and pain. It’s a magical world where women can be anything they want—eccentric, angry, hysterical, slutty, happy, indecent or powerful—without any men pouring cement over the saplings of their desires. Ravindra’s pain and frustration with a society that still disregards women’s aspirations is palpable as she creates a world of trees devoid of men and functioning solely through women’s minds. This book is a much-needed blow to the dominant paradigm that perceives female friendships as a recipe for jealousy and failure set by those in power.

In the shallow pool of Nepali novelists who write in English, writers like Manjushree Thapa, Samrat Upadhyay, Shradha Ghale and Prajjwal Parajuly, with their internationally acclaimed books, paved the way for emerging literature in English. Ravindra’s debut novel has added a new milestone on the road inaugurated by her predecessors. She gives a bold, independent voice to the women who are mostly only victimised and pitied. By representing Madheshi female protagonists, Ravindra has shown her readers the side of Nepal that Nepali writing, especially Anglophone Nepali writing, has long ignored. ‘The Woman Who Climbed Trees’ is a valiant ode to womanhood’s spirit and a heart-wrenching tale of the conflict between the inner and outer world in search of a home.

The Woman Who Climbed Trees

Author: Smriti Ravindra

Year: 2023

Publisher: HarperCollins India

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu.jpg)