Books

Exploring the duality of tradition and modernity

Kishor Sharma’s ‘Living in the Mist’ explores how the Rautes resist new ways of life, highlighting the complex relationship between photography, culture and the evolving socio-political landscape of Nepal.

Niranjan Kunwar

We know that discourse around art practice is influenced by technological advances. Photography is no different. More than other forms, this medium straddles a liminal space between art and science, its value and utility a topic of criticism as well as fascination, ever since its invention in France in the 1820s. At its advent, the required bulky tools were accessible to only a few. Those involved were mainly attempting to figure out its social purpose. Many of these early practitioners sought to capture painterly images influenced by the dominant art form of the era. In the 1870s, France began using photographs for surveillance and as a source of evidence in criminal courts. By that point, the technology had already evolved; cameras were more readily available and photographs became coveted artifacts useful for recording memories.

Yet, in a 1931 essay, Walter Benjamin lamented the industrialisation of photography, nostalgic for the 1840s when the field was ultra-niche. He was reacting to photography’s mass use, recoiling from the documentation of grotesque images of wars, famines and human ugliness. Photography was rapidly decoupling from its closest cousin, painting, the realm of delicate minds and beautiful things. Ironically, in a 1973 article, Susan Sontag refers to Benjamin’s lamentation, claiming that it was only with “industrialisation that photography became an art”, a reaction against the utilitarians by those concerned with style, taste and conscience. And in 2023, this writer wonders how Sontag would respond to the expeditious technological inventions of the past three decades—the creation of the Internet and the proliferation of digital images via smartphones and social media. We are at a precipice, caught up in intergenerational culture wars and anticipating a future dominated by Artificial Intelligence.

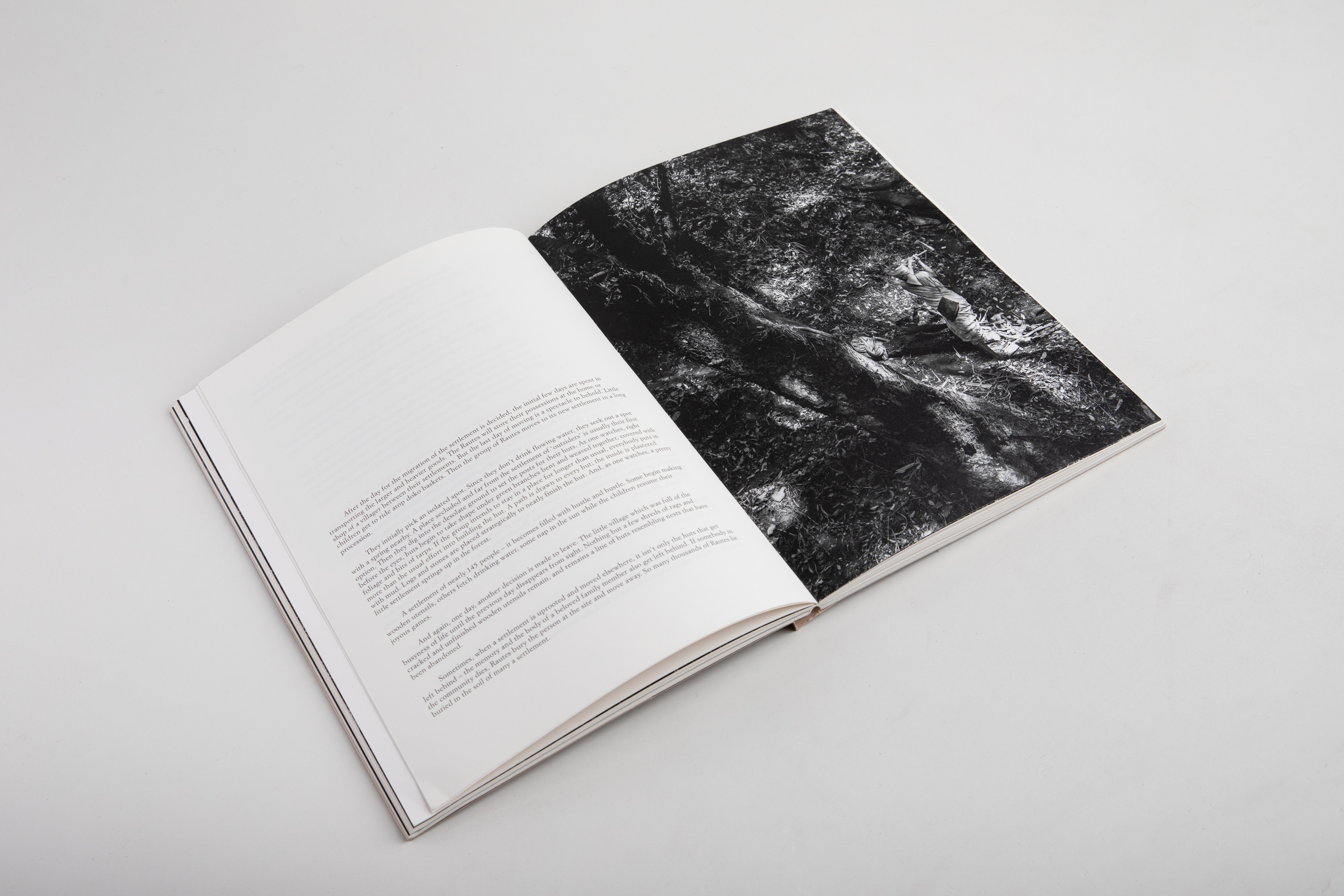

With this in mind, I entered Patan House, a small building on a long-term lease by photo.circle, to check out an exhibition by Kishor Sharma, ‘Living in the Mist’. It’s a small show contained inside a small room. The work itself is not new. Sharma’s larger exhibition with a longer title, ‘Living in the Mist—The Last Nomads of Nepal’, was one of several attractions of Photo Kathmandu in 2015. The current show, on display at Patan House until the end of November, features similar photographs, similarly rendered in black and white. The nomads from the 2015 subhead refer to the Raute people of Nepal, who still adhere to their nomadic lifestyle in the western districts of Nepal.

Sharma, who grew up in the eastern region of Nepal, first encountered the Rautes in 2011 as part of an assignment for a workshop. That time, he took a few photos, which were subsequently published. Sharma mentioned this during a panel discussion on October 11—the day of the show’s opening—explaining that since he was trained in Communications and Journalism, his focus in 2011 was more straightforward and goal-oriented. Soon after, in 2012, during his time at the Danish School of Journalism, he received proper encouragement to follow up with the Rautes. He also began thinking more deeply and broadly, not just about this particular project but about the scope and impacts of photography in general.

Sontag put forward the idea that to photograph is inherently an aggressive act. “To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have. To photograph is to turn people into objects that can be symbolically possessed (New York Review of Books, October 18, 1973).” Sontag does acknowledge the various uses of photography in the modern world as “a social rite, a tool of power, a defense against anxiety.” The stakes continue to get complicated as the world gets more digital and images become more ubiquitous.

photo.circle was founded in Nepal in 2007 as a platform for diverse photographers, but its vision is unambiguous. The founders intend to “nurture unique voices that document and engage with social change in Nepal.” This intention provides further clues to Sharma’s ongoing exhibition—the photos of Rautes were not propped up solely for our aesthetic pleasures, nor are we meant to simply comment on the quality of light, the scale of the images, or to get sentimental about the past. In fact, one could argue that in terms of artistic innovation, the exhibition does not offer much. This century is distinguished not by the kind of images found in Sharma’s collection (painterly retrospectives evoking the early 20th century) but by the “poor image”—low-res compressed pictures like memes, thumbnails, screenshots—whose meanings arise from being modified and circulated. (Farago, NYT, October 10, 2023)

So what’s the value of ‘Living in the Mist’? The organisers have unfurled multi-layered options for engagement—the exhibition is only a small doorway to Sharma’s evolving journey that spans over a dozen years. Be sure to delve into the accompanying book, also published by photo.circle, which includes Sharma’s personal narratives and notes. These reflections are a testament that attempts to counter Sontag’s charge. The words reveal a Nepali trying to understand Nepal and its people. Together, the words and images begin to address and resolve the many purposes of photography—Is It art? Is it documentation? Or is it more about the process, which encapsulates individual growth and leads everyone towards a shared understanding?

Since his first encounter, Sharma has travelled to the western districts numerous times to find the Rautes and commune with them. He wasn’t interested solely in capturing their portraits and outfits. He began getting interested in how they were perceived by the villagers they passed by. He felt the need to slow down to read instructive anthropological texts. At one point, the Rautes might have numbered in the thousands in Nepal, but these days, their population has dwindled to about a hundred. They mainly barter to survive, receiving grains from the community in exchange for pots and pans they make. As Nepal modernised, there have been consistent attempts to “civilise” the Rautes and bring them into the spheres of “development”. The state wants to provide citizenship cards to them, even land, and to send their children to schools. These markers would bolster government data and please Western donors concerned with education and economic productivity.

Yet, this kind of simplistic framework shirks larger ideas and deeper concerns. ‘Living in the Mist’ could be viewed as a troubling metaphor for the postmodern, globalised world that tugs at individual concerns (career, home ownership) and poses pertinent questions to politicians, media professionals and Instagram influencers seeking likes.

To do justice to this project, one must situate it in the context of Nepal’s socio-political landscape, which is still nursing a hangover as a result of the exclusionary Panchayat era policies. One must also remember that Nepal’s economy is largely dependent on foreign aid and remittance from migrant labour. “Development” has been a buzzword since the early nineties when the population embraced democracy and the state freed the market. During that chaotic decade, when these dynamic forces crashed head-on with the Internet and swathes of Nepalis began migrating to various countries, it was easy to forget our Eastern culture and indigenous roots. Even today, mainstream newspaper headlines describe the Rautes as “the ones who don’t know” and “who are from the jungle”, among other things. Viewed from a capitalistic, industrial lens, they appear as ignorant fools without skills. Yet, Sharma wondered, “What could we learn from them?”

During the panel discussion, Dhirendra Nalbo, a co-founder of the Open Institute of Social Science, mentioned that since he is properly integrated into modern society, he can’t afford not to send his children to school. He doesn’t even have the luxury of entertaining that option. For the Rautes, that question is still alive, profound and loaded with meaning. Many of them openly question our modern values—Why send children to schools? Why get citizenship cards? We have been living like this for generations and we like it this way. To that end, the Rautes might be more liberated than us, more courageous, more in tune with nature and less anxious; their lifestyle a successful resistance against social conformity and modernism.

17.9°C Kathmandu

17.9°C Kathmandu