Books

In Nepali literature, constructive criticism is rare

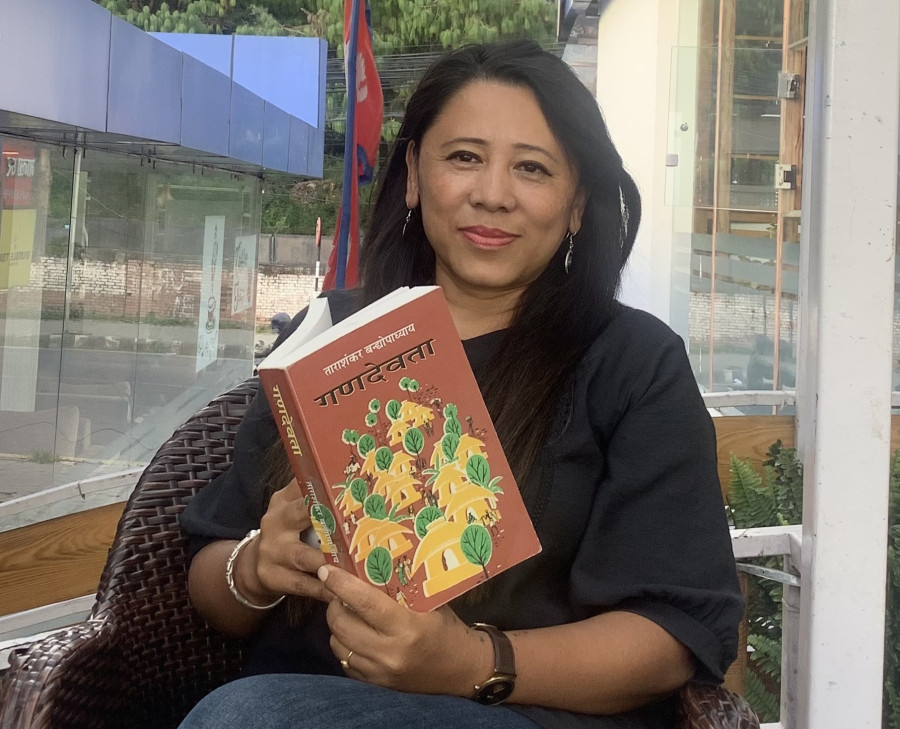

Bina Theeng Tamang talks about literature and her struggles within the literary community.

Manushree Mahat

Bina Theeng Tamang is refreshingly straightforward. Sitting on her scooter, the whooshing sound of the wind holds no candle to her loud and bold voice. She talks about her role as a teacher and vice-principal at a government school, her background in health studies despite her desire to study Nepali literature, and her 28 years living in Budanilkantha. Our conversation flowed effortlessly, even before we had reached the cafe.

Tamang is both an author and a teacher. She teaches multiple subjects at her school, although Nepali and health is her forte. She prides herself as an educator, but it is writing and literature that has carved her name in the literary spheres. She has published three books: a short story collection titled ‘Chuki’, ‘Rato Ghar’, which is a poetry collection, and ‘Yambunera’, her second short story collection.

When did books and reading first enter your life?

Books and reading became a part of my life in Hetauda, where there was a variety of literature available. Although there weren’t many books in the market back then, comics were a common sight. In today’s world, phones, televisions, and the Internet offer endless entertainment options. But during my childhood, things were different. We would spend hours playing and talking with friends and neighbours, or we would read. For me, books held a special appeal.

Our school had a library where I would borrow and read books. I remember feeling a bit overwhelmed by thick books, so I opted for the smaller, thinner ones. Two books, ‘Sumnima’ and ‘Basanti’, left a lasting impression on me. I confess, I miss the books from the old days. It seems that modern literature lacks the same depth and impact it once had.

Why do you feel that literature these days is lacklustre?

I believe modern literature often falls short because its characters are forgettable. When I reflect on the books I’ve read over the years, it’s the characters from early literary works that have stayed with me. For instance, Sakambari from ‘Sirish Ko Phool’ remains vivid in my memory due to her defiance of societal norms. The way these characters were crafted makes me wish I had written them myself. Sadly, such memorable characterisations are scarce in today’s literature.

Additionally, I think literature could flourish in a more intricate way through critique. In Nepali literature, meaningful criticism is rare. However, it's a critique that provides writers with a nuanced understanding of their work. The challenge lies in finding a balance between praising an author and harshly criticising their work. If we create an environment that supports writers while encouraging them to acknowledge the flaws in their writing, we can certainly expect better, more relatable literary works.

What feedback did you get from your audience after your works were published?

I noticed a lack of constructive criticism in the feedback for my own work. Those closest to me praised my writing, which made me feel happy, but there were a few instances where someone delved into the intricacies of my writing, pointing out its flaws. Looking back at my earlier works, I now see deficiencies in my writing and characterisation. There's also a segment of my readership that doesn't accept me as a Nepali author.

I believe writers and readers can create a space where they appreciate and critique written words without being too extreme.

Do you think writers with different values can find common ground in expressing their opinions on each other’s works?

Certainly. Unfortunately, this isn't often practised in our society.

Anton Chekov and Maxim Gorky, for example, critiqued each other’s works yet maintained a strong friendship. However, finding such balance is challenging in our circles. The world is diverse, and differing opinions shouldn't lead to personal attacks. It's as if we fear each other's opinions to the extent that honesty and sincerity are sidelined.

Writers benefit from unbiased opinions and constructive criticism. Genuine friendships with authors who offer honest feedback, rather than just praise, are valuable and sincere relationships worth cherishing.

You talked about the lack of critique in Nepali literature. What role do you think the media plays in providing a platform for authors?

The media plays a crucial role in promoting authors, especially in launching their careers. I remember when I started writing, authors featured in newspapers would create a buzz. Sometimes, people didn't even know what they had written; their photo was just there.

I too hoped to see my stories in newspapers, but it was tough, especially initially. Media often favours established authors and hesitates to support new writers. Once you've published your first work and received positive feedback, navigating the publishing industry becomes easier. But finding a platform for that debut, the first piece is challenging.

What challenges have you observed in the literary community?

Being a writer isn't the most stable job. We constantly learn, enhance our writing skills, and explore new topics and themes. There isn't much money in writing, making it nearly impossible to rely solely on it for a living.

I'm a teacher, which provides stability. However, in my decade-long writing career, my mind is always occupied. Characters and words from my stories linger, even when I'm at home. I don't just unwind; my thoughts are filled with my literary creations.

That's why I believe being a writer requires a strong heart and a genuine passion for the craft.

What motivates you to keep writing despite the challenges faced by the writing community?

It’s my identity. I want to leave my mark on the world, and writing is my means to achieve that. Once I began writing, there was no turning back. My books reflect this; I embed a part of myself in my stories.

Why did you choose to name your collection ‘Yambunera’?

This choice is deeply connected to my identity. I believe writers, much like politicians, engage in politics, but our power lies in our pen, not politics. I use language to delve into identity politics, and that's where ‘Yambuneru’ comes in. ‘Yambu’ means Kathmandu, and I want people to recognise that. Yambu is my foundation; it’s my home. I want this intrinsic part of me to hold value for others too. Some people don't see me merely as a Nepali language writer; they label me as a Tamang writer. I am both—a Tamang and a Nepalese woman and writer. I want my stories to echo that truth.

Bina Theeng Tamang’s book recommendations:

Grapes of Wrath

Author: John Steinback

Year: 1939

Publisher: The Viking Press

Set in Oklahoma in the 1960s, Grapes of Wrath is a story about the economic struggles of farmers whose cropshave been destroyed by a dust bowl. The first line of this book is captivating and sets up the story about the dark life of the people desperately seeking a better life.

Crime and Punishment

Author: Fyodor Dostoevsky

Year: 1866

Publisher: The Russian Messenger

This is a fascinating story about Raskolnikov, who commits a heinous act of murder. I think it’s a testament to Dostoevsky’s writing that we sympathise so much with Raskolnikov’s character despite what he’s done.

Autobiographies of Maxim Gorky

Author: Maxim Gorky

Year: 1913-1923

Publisher: Citadel Press

The book delves into the life of the author Maxim Gorky in a way that evokes despair at the difficult life Gorky had to live. Reading Gorky’s novels and being privy to the person that he was, was interesting and saddening.

The Vegetarian

Author: Han Kang

Year: 2007

Publisher: Portobello Books (English)

The Vegetarian tells the story of a woman who decides to stop eating meat and the tragic events that follow through the perspectives of her husband, brother-in-law and sister. I was captivated by the beautiful writing, which skillfully highlighted the importance of feminism.

Ganadevta

Author: Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay

Year: 1942

Publisher: Bharatiya Jnanpith

Ganadevta portrays the challenges faced by Indian villagers. Its realistic and detailed writing vividly captures the characters’ dimensions and struggles, unfolding their stories in a deliberate and moving manner

23.39°C Kathmandu

23.39°C Kathmandu