Books

Correcting the historical narrative

‘The Public Life of Women’ is built on the archival memories of the collective struggle of Nepali women to be seen and heard.

Amish Raj Mulmi

The history of Nepal, like most histories of nations and states, is a history of its men, with little attention paid to archival and narrative research on the role of women in Nepali history. As such, our historical narratives present an incomplete picture of our past, a deviation that suggests women had no role to play in Nepal’s past. Such exclusion and invisibility continue to shape our attitudes even today, as seen in how the state emphasises discrimination between its male and female citizens.

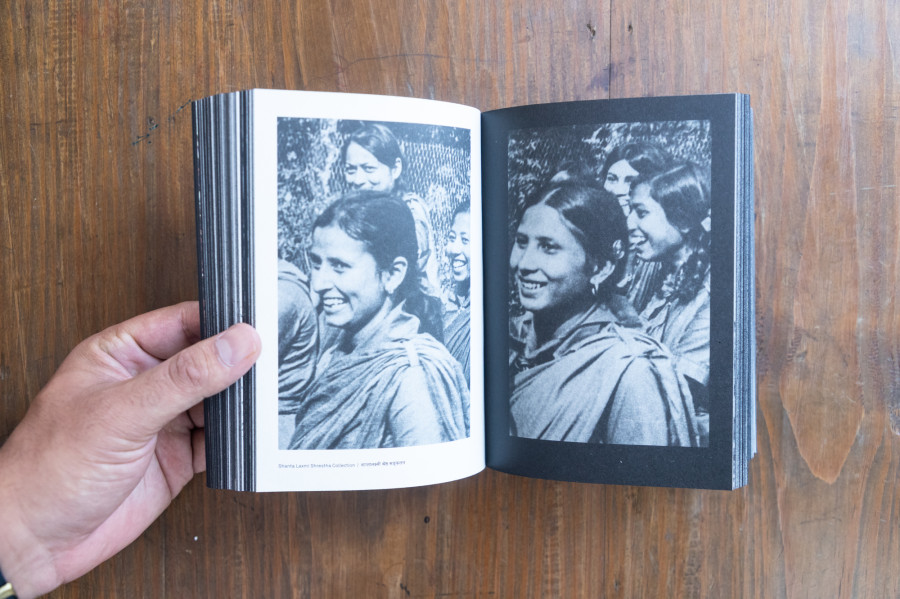

Nepal Picture Library’s ‘The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project’ corrects this narrative of maleness. Conceived as a public exhibition of photo archives nearly five years ago, ‘The Public Life of Women’ “grants us the ability to create other genealogies for our present and our future”, as its curators Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati and Diwas Raja KC surmise. It does this through a collection of photographic memories that emphasise, through material histories, Nepali women’s presence in the public sphere.

The result is a volume that cuts across generations and is built on the archival memories of the collective struggle of Nepali women to be seen and heard. Because it is primarily built on photographic archives from more than a hundred contributors, both the exhibition and the book are dependent on the medium of the photo itself to recreate such histories. The earliest photo dates back to 1935, where a group of women and girls, with pioneering educator Chandra Kanta Devi Malla in the centre, sit around a framed photograph with open books, marking the beginnings of girls’ education in Nepal through a school in Makhantole, Kathmandu. As such, the book is not just a visual history of Nepali women but also the story of modern Nepal itself.

Divided into five sections that broadly encapsulate the experiences of Nepali women in the political sphere, education, arts and literature, feminism and public awareness, and during their travels abroad, ‘The Public Life of Women’ forces us to reckon with the struggles of Nepali women to assert themselves by way of material histories. It begins with a grainy image from 1947, in which we can see mothers holding their children while coming together to form the Nepal Women’s Association against the Ranas, an extraordinary moment in Nepal’s political history that is also tinged with the private lives of women.

The history of women in democratic politics in Nepal is often reduced to a few names, most of whom are represented in the collection. But so are Prem Kumari Tamang of Nuwakot and Lal Maya Tamang of Dhading, who were imprisoned in 1961 for protesting Panchayat rule; ‘Mechi ki Didi’ Saraswati Rai, who was forced to withdraw her name from the 1959 elections after men told her “the timing was not right”; and Uma Devi Badi, who protested against caste-based discrimination against Badi women in 2007.

Some remain unnamed even in this recollection, such as the district heads of women’s class organisations during the Panchayat and the Tharu women from Dang who led a revolt against landlords in 1980. The latter portraits reveal a different kind of resolve, one heightened by the fact that they wear fabulous ethnic jewellery and massive silver earrings while staring at the camera in defiance. In an era where the mugshot has become a viral sensation, their portraits can be seen as emphatic defiance in the face of generational discrimination and marginalisation.

That the political sphere is the first step towards assertion for Nepali women is never too far away. The collection moves from different moments where women have organised themselves, such as in 1981 after the rapes and murders of Namita and Sunita Bhandari in Pokhara and during the Maoist civil war. This reiterates the contributions of Nepali women to democracy and civil rights in the country, although whether Nepal’s political parties themselves have succeeded in overcoming their patriarchal mindset remains to be seen.

The collection thereafter recreates Nepali women’s struggles towards education, a struggle that also pushed the women into public life ‘through the pursuits of study and learning’. The rest of the archive then flows into the creative life of Nepali women through women’s writings, magazines and print culture; the participation of women in NGOs and grassroots organisations that worked on gender issues; and finally, ‘Out in the World’, a section that ‘attempts to capture the wanderlust of Nepali women’. While the focus on NGOs and grassroots organisation is commendable, such an emphasis on aid-driven collectivisation also shifts the lens away from the enterprising Nepali woman—such as those who run the neighbourhood kirana pasal (grocery store), start home-based industries or pre-internet-era entrepreneurs. But then, readers are bound to demand more from any archival collection such as this despite the limitations of its sources of history.

What emerges from the collection is an archival repository that is not a telling of history ‘beholden to the logics of progress’, as curator KC says at the end, but a counterpoint that allows everyday histories to emerge from the dogma of feminism. It is an eye-opening historical text that stands out for the efforts of the curators.

That such a collection is dependent on photographs in the recreation of history results in an urban-rural hierarchy, both through the accessibility of the camera or the photo studio, and because it is primarily the urban woman’s perspective of the world. One could also argue such a hierarchy results in the under-representation of memories and archives from both the Himalaya and the Madhes, which have experienced different trajectories of both women’s history and feminism. Could the gender inequality of the 2015 constitution—and the resultant protests after its promulgation—have been included as archival history? Perhaps. But these are minor quibbles in what is a seminal text, one that reminds us that ‘The Public Life of Women’ is only the beginning of an attempt to correct the narratives of the past.

—

The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project

Curators: Diwas Raja Kc, NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati

Publisher: photo.circle

Year: 2023

12.62°C Kathmandu

12.62°C Kathmandu