Books

Nepali literature is progressing, albeit slowly

Richa Bhattarai talks about the reading culture in Nepal and the growing representation of all sections of the society in its literary scene over the years.

Manushree Mahat

There are hobbies, and then there are professions, and Richa Bhattarai adeptly balances these two aspects of her life through her love for books. As the executive member and communications officer of Nepal Literature Festival, she channels her passion for literature by uniting voices from various art and literary spheres onto a single platform. Bhattarai is also the external affairs associate at the World Bank and currently resides in Washington DC, USA. She has authored ‘15 and three-quarters’, an anthology of short stories.

In this interview with the Post’s Manushree Mahat, she delves into her journey as a lifelong reader and shares her insights as an active contributor to Nepal’s book community.

How did you start reading? How has your taste evolved over the years?

I grew up around books and between people who held literature in the highest regard. Both my parents were enthusiastic readers, so they always encouraged me and my sister to spend leisure time reading. Finding age-appropriate books back then wasn’t easy, but my father made sure to regularly discover and buy books for us. In my early years, I was introduced to Nepali literature, and I remember spending a lot of time engrossed in magazines like ‘Muna’ and ‘Chature ra Likhure’. I also explored Hindi literature, and one that particularly fills me with warmth as I think about it is reading the Indian monthly magazine ‘Chandamama’. Our home gradually became a delightful mess of magazines and novels scattered around.

As time went on, my reading preferences grew. In my early 20s, I was drawn to fiction—young adult fiction and fantasy novels like Harry Potter and The Hunger Games filled me with joy in a way that still makes me smile when I think about those books. And fiction has remained constant for me over the years.

These days, I find myself reading more contemporary, realistic, and historical fiction than I used to. Among them, I relate to books written by female authors—their experiences and depictions speak to me.

How has the portrayal of women and marginalised groups changed in literature?

When I was young, most of the authors I noticed in the market were men. Reading books featuring female characters written under the patriarchal lens of the olden days feels disappointing and limiting now. Even when I joined the Nepal Literature Festival team about a decade ago, the books I saw mostly represented men and the dominant castes of our society.

But what brought me immense relief and joy was witnessing the expanding representation in the literature landscape over the years. In the following three to four years, our literature community visibly grew and diversified, offering a platform for marginalised groups and female voices to share their stories. Books like ‘The Woman Who Climbed Trees’ by Smriti Ravindra, written by a woman, depicting women’s issues and psyche, make me believe that literature has made strides in embracing a broad range of ideas, experiences and expressions.

Books depicting the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community are being talked about more these days. Niranjan Kunwar’s ‘Between Queens and Cities’ is an example of the increasing adaptability of our reading market. Although diversity and inclusivity are expanding, there is room further to highlight the voices yet unheard in the literary arena.

To what extent do you think reading is a privilege?

In our society, reading is definitely a privilege. The way I had almost unlimited access to books all my life is also a privilege. Since both of my parents were teachers, they understood the importance of reading and literature and instilled those values in me.

Despite coming from a middle-class family, my parents consistently bought me books because they considered reading to be the best kind of investment. But many don’t have the monetary resources for such literary privileges.

Nowadays, having time to read feels like a privilege, too. Being a new mother, reading has slipped down my list of priorities. I used to proudly tell my mother that I could finish novels in a day while she took weeks. Life has a funny way of balancing things; now I’m the one who hasn’t completed a book in the past few weeks.

What are some differences you’ve noticed between Nepali and English Literature?

The main difference is that in comparison to Nepali literature, the English counterpart is incredibly rich and vast. There is far greater exploration and experimentation with styles, themes and stories there. Nepali literature, on the other hand, is still growing—slowly trying to keep up with the changing winds.

As someone who reads a lot of English-language books, I can understand their attraction—they are very diverse in terms of themes, voices, and experiences they portray. Nepal is a small country, and a lot of our literature is still limited to a particular set of ideas. Catering to a large audience by producing and encouraging authors and artists with divergent perspectives and experiences can go a long way in ensuring diversity in our literature and greater engagement from the audiences.

Do you believe there is such a thing as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ literature?

I absolutely loathe the separation of books into ‘high’ and ‘low’ literature.

Using such terms can make writers and readers feel ashamed of their preferences. Romance, for example, often faces this kind of bias. It’s unfair for people to have to explain why they like certain genres. We should remember that we can critique writing without attacking entire genres.

Of course, the discourse around the contents of certain books—especially if they promote harmful ideas—is important. This is also more than valid when it comes to work targeted at younger readers who are easily influenced.

Richa Bhattarai's book recommendations:

Americanah

Author: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Publisher: Alfred A Knopf

Year: 2013

A beautiful book by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, ‘Americanah’ is a treatise on culture, history and lifestyle, and it explores the themes of race, language and migration. I first came to this book while trying to assimilate into my life in the US.

The House in the Cerulean Sea

Author: TJ Klune

Publisher: Tor Books

Year: 2020

TJ Klune’s book is deceptively simple; it looks like a children’s novel, but the diverse set of characters and the heartfelt message of belonging, friendships and respect it delivers makes it an enjoyable read for all ages.

Sister of my Heart

Author: Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Publisher: Doubleday Books

Year: 1999

Divakaruni’s book delves into two girls whose lives have been intertwined since birth; they are sisters in all the ways that matter. Friendship is one of the major themes of the book–it is both beautiful and heartbreaking seeing them navigate their complicated lives together.

A Little Life

Author: Hanya Yanagihara

Publisher: Doubleday Books

Year: 2015

This is a difficult book to read–topics of childhood trauma, rape, and sexual abuse take up a significant portion of the novel. Yanagihara delves into the themes of friendships and tragedy in a devastating story that will make anyone think about this book for a long time.

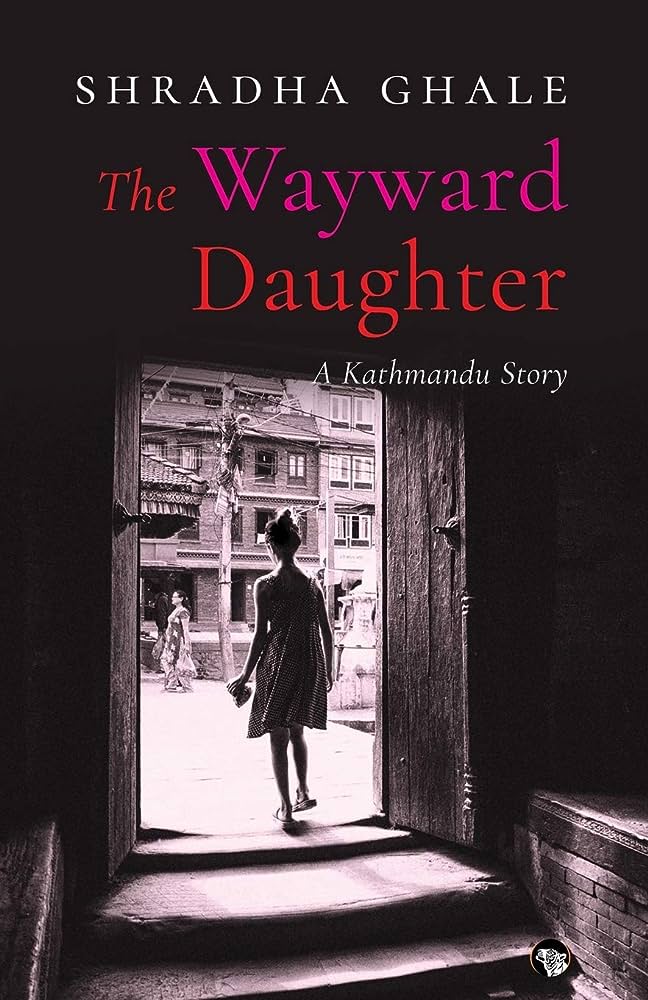

The Wayward Daughter

Author: Shradha Ghale

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Year: 2018

The Wayward Daughter is a relatable story for many of us born during the Maoist Civil War. The book is a moving exploration of class, caste and gender norms through the perspective of a young girl.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu