Books

A daughter’s tribute

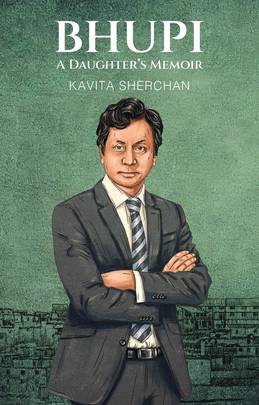

Kavita Sherchan paints an intimate portrait of her father, Bhupi Sherchan, in an upcoming memoir.

Manushree Mahat

Kavita Sherchan welcomes me with a warm smile at the doors of Bhupi Kanti Niwas. As I enter the house, I’m greeted with framed photos of the beloved poet Bhupi Sherchan and his family. As we walk the short distance between the door and the living room, I can’t take my eyes off an ambiguous painting displayed against the walls. Kavita enthusiastically tells me it is based on her father’s poem ‘Hami’, painted and gifted by Uttam Nepali. Her appreciation for her father’s work is apparent.

Her eyes twinkle as she talks. There is excitement in her eyes as she tells me about her life, her book, and her beloved father, Bhupi Sherchan.

Kavita grew up in a lively house. Poets and writers used to drop by for an occasional chat and immerse themselves in her father’s singing and poetry recitation. Even now, when she hears Nepali folk songs and melodious jazz tunes, she is transported back into the warm, musical soirées her parents held. Growing up around people who held literature in the highest regard and listening to them discuss the intricacies and beauty of art shaped her career in writing and literature.

Books came into her life quite early. She states, she was intrinsically pulled towards her father’s library, often swept away by the fantastical comforts of reading. She was an ardent follower of Jane Austen’s works; she had found herself flipping through the pages of Elizabeth and Darcy’s story on more than one occasion. At the time, she mostly read stories written in English, and it wasn’t until much later that she started enjoying Nepali literature too.

“My father never forced us to read anything we didn’t want to. He didn’t want us to feel suffocated by his views. This allowed me to explore and experiment with all kinds of literature,” she recalls.

Kavita is no stranger to rumours. Artists and authors were judged through the narrow lens of prejudice back then. She often found it hard to escape from the cruelty of these whispers and the murky light writers were painted in. The love that people had for Bhupi Sherchan was immeasurable, but some of the rumours about her father’s bachelor lifestyle were hard to shake off.

Her mother, Kanti Sherchan, always told her to ignore such rumours. Kanti was headstrong, and smart in handling people’s judgements. She was also deeply dedicated to her husband and his work. Kavita fondly recalls the joy on her parents’ faces as her father gleefully recited his poetry to her mother. She also remembers the days when her mother, with little to no regard for her own health, would spend days with her father at the hospital when he was unwell. They had an unwavering commitment to each other.

Kavita didn’t think she would pursue a career in writing. As someone who loved math and science as a teenager, she began dreaming of becoming a doctor. She received a scholarship to study medicine in China but returned back after realising that the frantic lifestyle (of a doctor) wasn’t what she wanted. She finished her bachelor’s in Psychology and English Literature. Later, she did her master’s degree in English literature and soon began working as a journalist.

Years passed, and between them, she encountered people who asked her if she would ever write a book about her father. “I didn’t think I would do justice to his life. A biographer should be objective when it comes to their work. As his daughter, I wasn’t sure if I could separate my personal feelings,” she says.

Nepal was dear to her; Kavita had spent her whole life tucked safely in her country’s embrace. She never imagined leaving Nepal, but the Maoist insurgency brought a drastic change in her worldview. On the day she had given birth to her son, the government announced a curfew that got them shut in Patan Hospital. A couple of days later, rumours of the ban being lifted were spreading, so Kavita and her family decided to leave the hospital.

However, on their way home, a mob surrounded their cars and started banging on the windows. She was terrified, cradling her newborn son in the backseat. The mob was threatening to burn their car. They lived nearby, and some people in the mob recognised her aunt and finally let them through.

At the time, Kavita didn’t think the political climate of Nepal was suitable for raising a son. She thought herself lucky to escape that mob, but anything could’ve happened then. Her son’s future was her priority now. After some discussions and planning, she and her husband moved to the Philippines, where she began working as a communications consultant at Asian Development Bank.

In December 2019, a friend contacted her to write a memoir about her father. At that point, she was still in the Philippines. “I denied the request then, but the guilt started eating me alive. This person was a complete stranger to my father, yet he asked me to write about him,” she says.

But between her job and making time for her family, she didn’t have the time to do much else. Then, the Covid-19 pandemic began, and the lockdown brought ample leisure time, so Kavita finally began writing the memoir.

She finished her first draft quite early, although going down memory lane was difficult. There would be times when her mind would feel like it was missing an entire chunk of memory—the niggling frustration of something missing wouldn’t leave her alone.

However, there is a chapter in which the words spewed from her pen to the paper without any struggle. The memory of a loved one’s death is painfully vivid, and Kavita could never possibly forget the sorrow that had consumed her on the day of her father’s death.

“It was the first chapter in my book that I could write with total clarity. Words and emotions hit me like an avalanche as I wrote about his death. I poured all my emotions into writing it, and this chapter was hardly changed during the editing, too,” she says.

Kavita realised that although she found it easy to analyse and critique others’ works, evaluating her own was challenging. She also found it much easier to write about Bhupi, the poet, than about Bhupi, the person. Reading about her father’s struggles and his past, and giving her fuzzy memories a life, was both tough and rewarding. But she didn’t stop writing, and after almost three years of work, ‘Bhupi: A Daughter’s Memoir’ was ready to be published.

“Every Nepali knows Bhupi, the poet. But not many people know him as a person. I hope that my honest words about my father, his life, and his poetry speaks to the people who already know about him,” says Kavita.

‘Bhupi: A Daughter’s Memoir’ releases on August 8.

10.63°C Kathmandu

10.63°C Kathmandu