Books

Humour beyond being funny

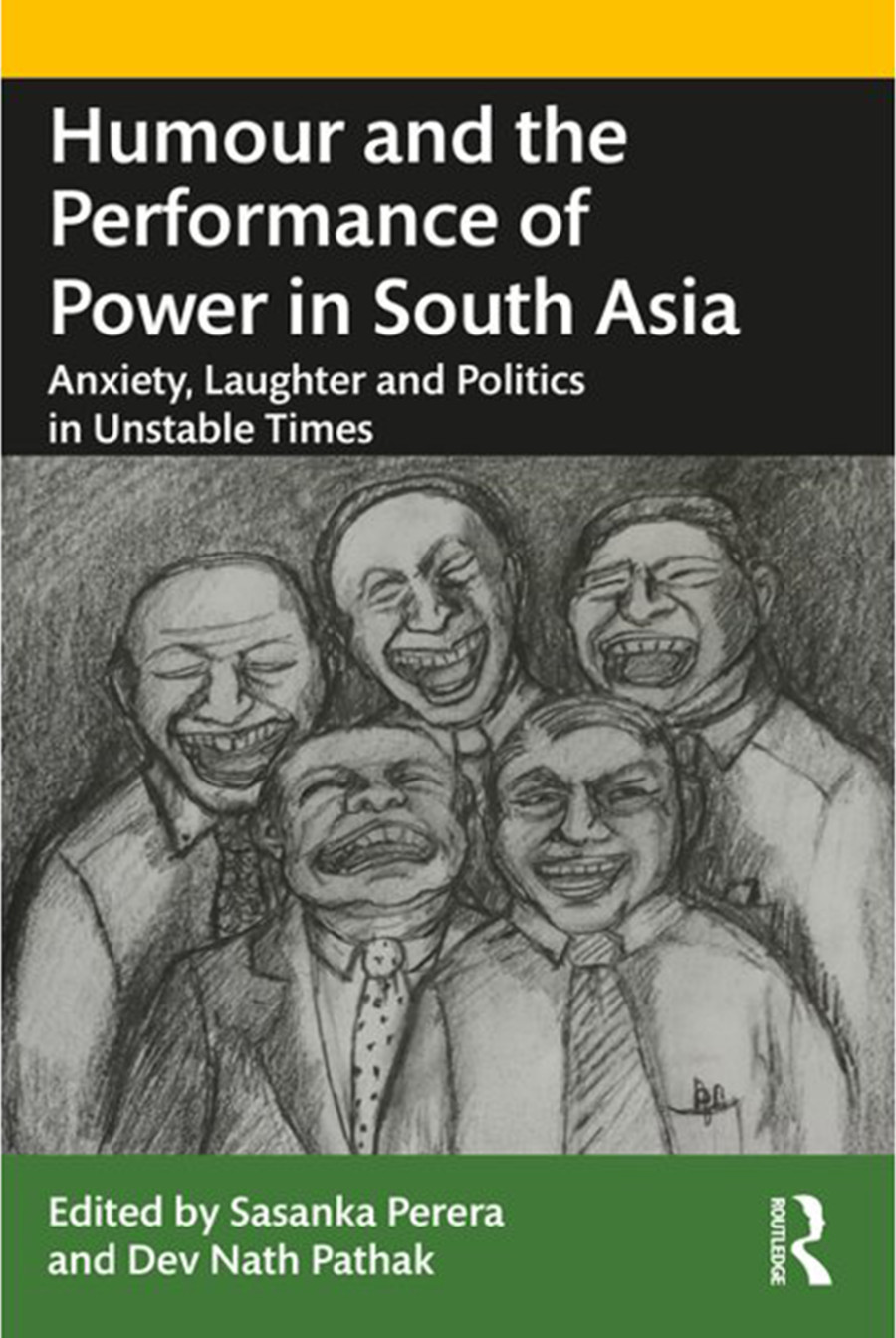

‘Humour and the Performance of Power in South Asia: Anxiety, Laughter and Politics in Unstable Times’ comprehensively captures the multiple discourses of social and political levity beyond its normative epistemologies.

Magna Mohapatra

The ‘serious’ study of humour and the enjoyment of humour is often considered to be parallax. But as Sasanka Perera and Dev Nath Pathak state, these two phenomena—if performed simultaneously—are not necessarily an obstacle to fathoming the cultural politics in South Asia, particularly in these troubling times (Perera and Pathak 2022: 2). Humour is well-known to portray the discontents of civilisation, often camouflaged in its own manifestation, and ‘Humour and the Performance of Power in South Asia: Anxiety, Laughter and Politics in Unstable Times' allow us to peek through the jokes into these discontents. The essence of what is funny is traversed by different stakeholders — the author themselves, the ones who produce the humour and the people targeted by the joke. One can expect a comprehensive understanding of the myriad meanings—beyond singular theorisations—of humour and its anxieties.

The book consists of ten chapters, with the first chapter elaborately introducing not just the scholarly contributions of all the authors towards comprehending political humour but also its interdisciplinary anxieties, namely, what humour signifies in its historical etymology, its contemporary role in cultural politics of South Asia, and its epistemological horizons within the disciplines of Sociology and Anthropology. Sasanka Perera and Dev Nath Pathak succinctly unpack the causal conditions of political humour and the often morally ambiguous connotations of laughter across ethnicity, religion, economic conditions, political affiliations, and everyday social relations. As they note, “The comic comes into existence when flexibility, spontaneity, agility and creativity are hindered. In this sense, in the context of the political upheavals and disruptions, which mark much of South Asia, it is no accident that political humour emerges, when democratic rights and personal freedoms are most seriously curtailed” (Perera and Pathak 2022: 6).

The complexities of tragicomic realities abound in their coherent as well as incoherent significations in the politics of South Asia. When is something considered funny? In what circumstances is a joke deemed hurtful? When is it racism and when is it an example of political satire? When is it a case of harmless and trivial banter and when can it be considered a source of serious rumination? When do jokes become subversive—a ‘weapon of the weak’(Scott, James C. 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. Yale University Press). How does humour manifest during political crises? When can humour attack the status quo and liberate the tortured soul? The authors in this book tackle some of these questions and more related to the manifestation of political humour across three thematic sections.

Under the first sub-theme titled, ‘Humour in Literary and Visual Subversions,’ chapters 2 and 3 broadly engage in historical, literary, and visual discourse of humour. In chapter 2, the author Divyendu Jha introduces us to distinctly Indian ways of thinking and laughing about colonial politics through satirical cartoons published in the English-language magazine called ‘Punch’ and other local Indian vernacular magazines. In chapter 3, Dev Nath Pathak analyses the literary fictional character called Khattar Kaka, who engages with Hinduism and its scriptural discourses in an irreverent tone. In this essay, critical humour questions the normative idea of religiosity and evokes self-criticism of Hindus’ practice of their religion and the contemporary religiopolitical intolerance in the country.

The presentations under the second sub-theme, titled ‘Folkloric Worldviews: Laughter as Performed Narratives’, comprises three chapters that engage in performative humour. In chapter 4, Prithiraj Borah gives us an insight into the work culture of tea gardens in India’s Assam state, and the subjective experiences of the Adivasi (tribal) plantation labourers who use strategic oral performances as a form of (in)visible resistance against their everyday oppressive work conditions. In chapter 5, Monica Yadav explores the subversive performances of jakari and ragni in the Indian state of Haryana, where dance-drama inverses gendered relations and counters the normative patriarchal relations in the North-Indian family structure. In chapter 6, Lal Medawattegedara tells us how the modern Sri Lankan folklore counters the normative idea of nation and symbolise a pluralistic narrative of ethnonational identities.

The third sub-theme, titled ‘Mediated Messages for Laughing and Thinking’, expands into four essays that focus on the mediated interpretations of humour through analysis of memes, jokes, and stand-up comedies. Chapter 7 explores the critical thought and political power located in internet memes. Here, Sasanka Perera argues that such humorous mediations are a form of anonymous political power that define and redefine political discourse in contemporary crisis-ridden Sri Lanka. In chapter 8, Sandhya A S and Chitra Adkar highlight the discursive feminisation of Nepali men through stereotypical narratives by the hegemonic Indian male gaze. In chapter 9, Sukrity Gogoi and Simona Sarma introduce us to the politics of performative humour through stand-up comedies that theatrically enact and portray satirical narratives in the context of Indian politics. In the final chapter, Ratan Kumar Roy analyses political jokes used in television news and digital platforms and their formation into a powerful discourse of politics embedded in the conceptual category of the ‘public’ in Bangladesh.

Taken together, the book comprehensively captures the multiple discourses of social and political levity beyond its normative epistemologies. Levity has historically been studied more by philosophy, psychology, and literature through vastly varying frameworks but has often been neglected in sociology and anthropology, especially within South Asian knowledge production. The present intellectual endeavour is also an effort by the editors to radically redraw the boundaries of sociology and social anthropology in South Asia beyond its geopolitics and invite scholars and scholarship to tread out of the fossilised and taken-for-granted comfort zones. One can also note the sly wit and sardonic tenor in their analysis of the cultural politics of humour that make the book an engaging read and, to an extent, enable the reader to both ‘seriously’ study as well as light-heartedly consume the discourse of humour— dismantling its inherent parallax. Definitely, Perera and Pathak, in studying humour, do not lack a sense of humour!

Mohapatra is a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Name of the book: Humour and the Performance of Power in South Asia Anxiety, Laughter and Politics in Unstable Times

Edited by: Sasanka Perera, Dev Nath Pathak

Published by: Routledge India

Hardback: Rs 1592 (approx)

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)