Books

Government should support translation of Nepali literature

The shortlisting of ‘Song of the Soil’ will hopefully make international publishers cast about for books coming out from our part of the world.

Aarati Baral

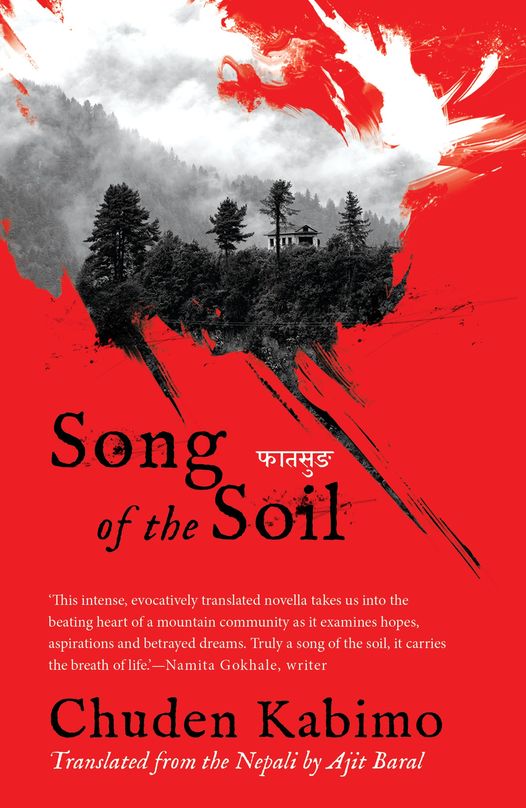

‘Faatsung’, a Nepali-language novel written by Chuden Kabimo and translated into English as ‘Song of the Soil’ by Ajit Baral, has been shortlisted for this year's JCB Prize for Literature. The INR2.5 million (NRS4 million) prize is awarded annually to an outstanding work of fiction by an Indian author. Authors shortlisted for the prize receive INR100,000 and their translators 50,000. If the winning work is a translation, the translator receives an additional INR1 million. All five books shortlisted for this year's award are translations—a watershed moment for Indian literature.

Apart from ‘Song of the Soil’, the shortlist includes Khalid Jawed's ‘The Paradise of Food’, translated from Urdu by Baran Farooqi; Geetanjali Shree's ‘Tomb of Sand’, translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell; Sheela Tomy's ‘Valli’, translated from Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil; and Manoranjan Byapari's ‘Imaan’, translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha.

Baral, a co-founder of FinePrint Books and the director of Nepal Literature Festival, spoke with the Post's Aarati Baral about his craft and the future of Nepali literature in translation.

‘Song of the Soil’, your translation of the novel ‘Faatsung’ has been shortlisted for the JCB Prize. How do you feel? What significance does this achievement hold for Nepali literature?

I am thrilled beyond belief. I could have never imagined ‘Song of the Soil’ being in the reckoning for a major literary prize when I first decided to translate ‘Faatsung’. Now that it has made it to the shortlist, it feels surreal.

When Geetanjali Shree won the International Booker Prize earlier this year for ‘Ret Samadhi’, many said it would do a world of good to the literature from the subcontinent. I agree with this view. A prestigious prize puts the spotlight on not just the winning book but also the literature of the region.

The shortlisting of ‘Song of the Soil’ will hopefully make international publishers and literary agencies cast about for books coming out from our part of the world.

How did you come up with the idea of translating ‘Faatsung’? What about the book piqued your interest, and what do you think drew the attention of the jury?

I first read the novel in manuscript form when Chuden Kabimo sent it to us for consideration. I fell for it and decided in no time to publish it. But the idea of translating it came much later when I edited it, coming to appreciate the novel better in the process.

The lyricism of Kabimo's writing, and perhaps the piquancy of the Darjeeling dialect, sealed it for me. Its story of the struggle for the identity of Nepali-speaking people in Darjeeling, popularly known as the Gorkhaland movement, resonated with me. This movement is not unlike the Maoist movement in Nepal, which started with lofty hopes for the country but ended up, after ten years of bloodbath, in a compromise benefiting only a few.

The jury liked how Kabimo wrote about a violent movement without resorting to violence. The book, in their own words, "[made] poetry out of brutal situations, but with honesty, humor, and gentleness."

What was your biggest challenge while translating the book?

Kabimo writes in short, simple sentences. So it was not that difficult to carry their essences across in English. But retaining the lyricism of the writing and the tenor of the dialogues was difficult. So was finding the English equivalents of regional words such as sikuwa, jhyampal, etc. In such cases, I had to opt for the most approximate terms.

What do we need to do to increase Nepal’s presence in the literary world outside Nepal? What about books written in languages other than Nepali?

There is no other way than to write more books. And not just any book, but great books. We need to give impetus to translation and encourage people with literary skills to take up translation too. The time is also right for carrying out translations. Publishing houses worldwide are now more open to publishing translations to diversify their lists.

I might sound pessimistic, but I don't see much hope for local languages. They are dying out, and very little is being written in languages other than Nepali and English. There is no market for books written in the local languages for publishing houses to be interested in either. Reviving local languages, I am afraid, is a lost cause.

As a publisher, what have you been doing to enhance the quality and quantity of translation in Nepal? What do we need to do to create a suitable environment for translators?

A publisher can only do so much. We can, however, play our part by being judicious about the books we translate, finding the right persons to translate them and rigorously vetting the translations, as a lack of vetting mars most translations. We have been doing just that over the years. Some of our translations—such as ‘Microsoft dekhi Bahundandasamma’ and ‘Khabuj’—have been well appreciated for the quality of translation.

I see hope for translation in Nepali writers writing in English. Manjushree Thapa, Muna Gurung, Prawin Adhikari, etc., have translated works of Nepali literature into English admirably. I have heard a score of other writers in English—with an MFA in Creative writing to boot—are showing interest in translation. If they could be encouraged to undertake translations with a little incentive, things would look up for translations.

However, we need concerted governmental and institutional support for translation to bring significant changes to the translation scene in Nepal. There is no incentive for translators, so we need to set up grants and residencies to inspire them to devote themselves to translation.

What skills do people need to have to become good translators? When and how did you start translating texts?

You cannot hope to be a good translator without a flawless understanding of the source language and a perfect command of the target language. If you have an ear for the rhythm of the original language and the writer's style, that's even better.

It helps to have patience and restraint too. After all, translation is a time-consuming and tiring job, and you cannot stray away from the text.

Apart from being a writer and translator, you are also an avid reader. What kind of books do you love the most? What are your favourites?

Although big into travel writing, I read books across genres. I particularly like long-sweeping novels about people in the throes of political churnings, like ‘A Fine Balance’ by Rohinton Mistry. I am a huge fan of VS Naipaul and Paul Theroux. I have read all of Naipaul's books except the last one, ‘The Masque of Africa’, which I found difficult to plough through. I have read most of Theroux’s books, including ‘The Great Railway Bazaar’, which, along with ‘An Area of Darkness’ by Naipaul, deepened my interest in travelogues.

The most recent books I have liked immensely are ‘Men in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker’ by Thomas Kunkel, ‘A Swim in the Pond in the Rain’ by George Saunders, and ‘Washingtonian Black’ by Esi Edugyan.

Many books in Nepal are awaiting translation. Which books would you like to translate in the future or want to see being translated?

Very few works of Nepali literature have been translated into English. So a translator working from Nepali to English has the luxury to pick and choose—from BP Koirala to Bhupi to Buddhisagar. I would like to see someone well-tuned to poetry taking up Bhupi's poetry. An iconic poet, he needs to be read outside Nepal. I would like to see some of BP Koirala's books in English too.

We need to translate books by younger, contemporary writers like Nayan Raj Pandey, Upendra Subba and Amar Nyaupane. I would love to translate ‘Kathmanduma Ek Din’ by Shivani Singh Tharu. Though stiff in places, it is one of the most rigorously written novels to have come out of Nepal.

What message would you like to convey to young people who love reading and writing?

Read everything you can lay your hands on—newspapers, magazines, guilty pleasures, serious fiction and non-fiction. You will find your way around books sooner or later and eventually develop a taste for a certain kind. If not, even better, you would have developed an eclectic taste! And write as much as you can. Start a journal. Always carry a notebook. Jot down ideas and impressions you have of people and places. Study people, note how they speak and look, and describe features that stick out. Read closely for the writer’s style. And be a part of the reading and writing community.

12.32°C Kathmandu

12.32°C Kathmandu