Books

Uncovering the life of Bishwambher Pyakuryal

The autobiography portrays the author's rather arduous journey from belonging to a small village in Bardiya to becoming a respectable name in academia in the heart of Kathmandu.

Madan Kumar Bhattarai

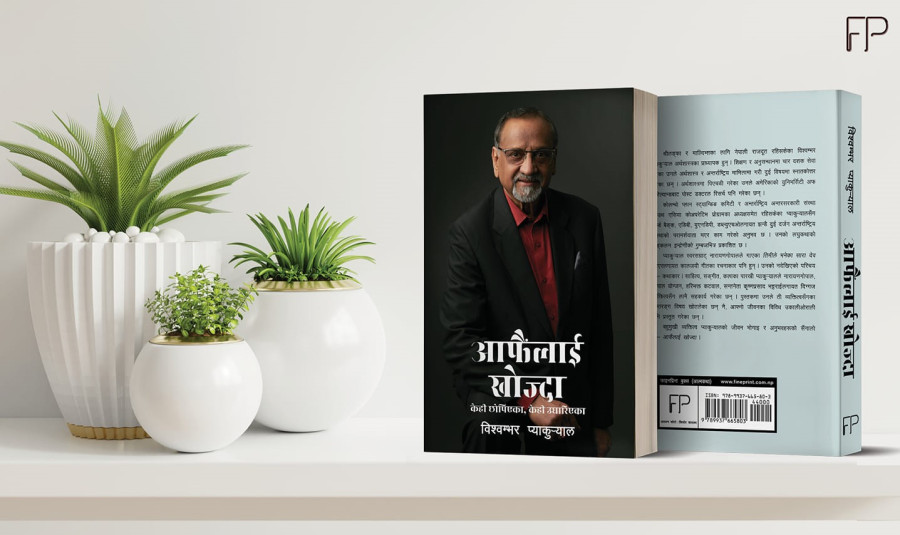

Bishwambher Pyakuryal, a noted economist, prolific writer, economic and development consultant, and litterateur, has added a new feather to his hat by bringing out an autobiography. Published only recently, on September 20, the very title of the book, Aaphainlai Khojda—Kehi Chhopiyeka, Kehi Ughariyeka (which could be loosely translated to English as Searching Oneself—Somethings Veiled, Somethings Uncovered) promises to uncover many things that he has faced and confronted in his decades-long career in the country's academia.

The book portrays a painful odyssey that took him from his place of birth, Guleria, Bardiya, to Kathmandu for education and his persistent struggles as an ‘outsider’ and finally as one of the well-known names in the faculty of Economics at Tribhuvan University. For those unfamiliar with his work, Pyakhurel has interacted with a number of leading stars of literature, culture, music, journalism and other creative aspects of life, besides his innumerable write-ups in national and international journals of repute and publication of around one and half dozen books that he has written, co-authored or edited.

Pyakhurel has undergone tumultuous experiences of encounters during his long career. These include an arduous struggle against poverty since childhood and difficulties he faced in the United States while working for his second Master's degree, his fifteen year-long legal battle with the Commission for Inquiry against Abuse of Authority, the hurdles he faced in getting a job in the only university of his time and trials and tribulations in terms of denial of promotion despite all attributes required for the position, and a nearly fatal episode that kept him confined at Norvic Hospital under ventilator support for 21 days. All these traumas have probably forced him to confess that human beings die several times in their life, maybe another reflection of his literary bent of mind.

Pyakhurel’s life is dominated by teaching and research as he put in 39 years at university and 6 years at school earlier. He has undergone several interactions and contacts with international agencies and established a solid reputation as a cerebral economist. Though a student activist sympathetic to Nepali Congress, he confesses that he never aspired to become a full-blown politician. He is also meticulous in laying down that politicisation of education has become the perpetual bane of our system irrespective of changes in its mode and appearance.

In the autobiography, he laments how the premier institute of higher education, Tribhuvan University, conceived with the noble idea of making it a centre of excellence, has turned worse and degenerated in recent decades. As his forte is economics, his observations that Nepal’s current status is on a rapid decline compared to the situation 44 years ago reflect a deep malaise in our system of governance and pursuance of policies.

For someone who has spent almost four decades in diplomacy and knowing him from close quarters for a long time, I was more interested in the 20th of the 22 chapters of the book that focuses on his stay in Colombo as Nepal’s ambassador to Sri Lanka. His strong-worded reading that one has to become ambassador simply for being insulted is rather a sweeping remark but deserves to be analysed for its perspective.

While we may have different arguments on his conclusion that the higher management in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was not at all responsive to his frequent reports, letters and other means of communication for getting instructions, there is no doubt that the chapter calls for some introspection on the ways and means of diplomacy including the system of appointing so-called cabinet-level ambassadors that Bishwambher has questioned both in its merit and practice.

While the book makes an interesting reading given the author’s wide spectrum of public relations that he has so painstakingly earned, it may be pertinent to also dwell with the downsides of the otherwise good autobiography.

First, despite claims that he was going to uncover many things, it seems Pyakhurel seems rather hesitant to pinpoint the names of exact persons and the modality of problems he faced and confronted as ambassador before he laid down his office after a little over two years. Probably, he may have taken some tips of being more diplomatic in this aspect.

Some chapters are repetitive, and that becomes evident when one goes through chapters 1st, 18th and 22nd. There is also no synchronisation between chapters 17 (which tends to give the impression that he was still in Colombo despite expressing scepticism of his stay) and 20 (which gives his rather horrible assessment of Foreign Ministry of Nepal after one year of his ambassadorship alleging that it had become a pawn of a handful of bureaucrats.)

Third and last, after reading the book, readers don’t find plausible answers on what we should do to reform the working mechanism in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, apart from the larger questions of making our economic policy serve the crying needs of our people and turning universities into a fertile area of teaching and learning, and research and development.

However, despite some of these obvious lacunas, there is absolutely no doubt that the book has added a new chapter in the annals of writing autobiography.

—————————————————————————————————————

Aaphainlai Khojda – Kehi Chhopiyeka, Kehi Ughariyeka

Bishwambher Pyakuryal

Publisher: Fineprint Books, Kathmandu, 2020

Pages 242

Price: Rs 700

22.11°C Kathmandu

22.11°C Kathmandu