Books

Women in South Korea Show Up, Speak Up

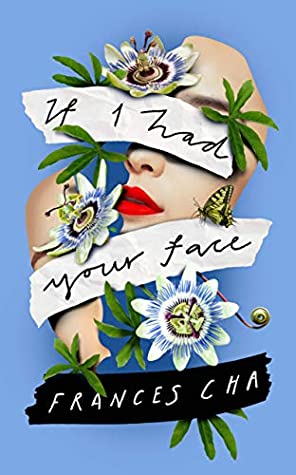

In Frances Cha’s If I Had Your Face the truths of the country are revealed thick and fast, and reiterated through characters and tropes.

Richa Bhattarai

You want to beautify yourself, look a little more presentable, appear hip and professional—what do you invest in? An outfit, perhaps. Accessories, a trip to the salon, a day at the spa. Would you go for permanent microblading of the eyebrows? How much would you spend; what limit would you set? Would you consider botox, a nose job, breast enhancement?

Plastic surgery is not usually a casual conversational topic, even in an appearance-focused society. But in South Korea, it is apparently fodder for chit-chat. In the very second page of Frances Cha’s debut novel ‘If I Had Your Face’, room-salon aspirant Sujin asks beautiful Kyuri where she got her eyes done. Out pour experiences of asymmetrical eyelids and aligned jawlines. Later, Kyuri confesses, “I really don’t understand ugly people. Especially if they have money. Are they stupid? Are they perverted?” Issues camouflaged under wraps of popular culture are laid bare in Cha’s novel.

Even the title lusts for another person’s face, and this wistfulness for perfection pervades the entire work. The four women narrators, each aiming for their version of perfection or at least stability, are grappling with challenges of their own. Ara, already saddled with a poverty-stricken background, has been rendered mute after an accident, and her only solace is a K-pop star. Her roommate, Sujin, wants to make it big in a “top ten-percent room salon”, an euphemism for sex work. Their neighbour Kyuri is already deep into this service, having loaned herself out to pay for her facial reconstruction. Meanwhile, in another flat, claustrophobic Wonna is worried about having a baby while her husband has been laid off. Then we have glamorous Miho who struggles in her artistic endeavors even as her fiancé cheats on her.

As readers we slide right into the midst of the characters, learning about their pasts that are all sad in their own way, their dreams for the future, the residue of hope they cling on to. The novel takes us from the bustling city of Seoul to the placid alleys of Cheongju, tracing the backstory of three of the girls that reveals so much about the aspirations and mentality of the Korean youth. It is a pleasure to journey alongside these young women as each of them struggle to find a niche, to propel themselves forward, to rise out of ashes. It is a reminder of the sameness that exists in all humans, no matter their heritage or nationality.

Cha, who reported for CNN in South Korea for a number of years, has revealed that she is quite adept in “writing for clueless Americans”, by which she means foreigners who need every bit of context and detail. She has managed to do that very well, ensuring the essence, the Korean-ness of her characters while also making the language and connotations accessible to the most blasé of readers. Deciphering the rich tapestry of Korean terms like chaebol and yoohaksang, sunbaenim and nunchi is exciting.

Even more alluring is this chance to gauge the intricacies of the sociology of Korea, with many superlatives to its credit that the author keeps referring to: the fastest growing economy, the highest suicide rates, and the sharpest declining birth rates in the world. The novel succeeds in putting names and faces to the Korean women (and men) that merely lurk within news stories, it humanises their problems and ushers readers into a culture that is so far from the ones depicted in mainstream Korean dramas, K-pop, and 10-step skin care routines.

The truths of this country are revealed thick and fast, and reiterated through characters and tropes: the plastic surgery industry, class divide, the highly competitive and nepotistic job market decrying maternity leave, infidelity and subterfuge, sexism and misogyny—even the naivete of Korean wives who pretend their husbands aren’t the ones keeping the room salons aflush. The narrators’ relationships are critically analysed, too, to unravel a spool of lies and half-truths hidden underneath a relatively smooth exterior.

In situations that are reminiscent of the movie ‘Parasite,’ visible parallels are drawn between the lives of the wealthy and the poor. It will strike readers how the rich population in all countries are so different in their obsessions and plundering, and yet how similar the poor – when Miho mentions the ‘Adidis’ slippers in her parental home, it could so easily be a scene of Nepal or really, any other country in the world.

Cha’s command over the English language and her sharp observational skills are discernible, that comes perhaps from her chequered background leading her from the States to Hong Kong and South Korea and back to the States. Her journalistic training is also evident in the research that has gone into the plastic surgery business, from the medical to the monetary.

And yet, after an introduction to strong, diverse and interesting women and a host of issues ranging from mental health and victim-blaming to personal space and infidelity, the storyline fizzles out, after only having superficially dabbled in them but not quite making an indentation. The women sometimes merge into each other, making it difficult for the reader to distinguish between them. The great friendship and empathising that is supposed to hold the story together never makes a satisfactory entrance. At the end, there is neither a fitting resolution nor a particular revelation. Perhaps this is just a reflection of the modern way of life: there is no closure. But mostly, the novel seems unable to reach the tall promises it makes when starting out.

‘If I Had a Face’ is readable, and enjoyable, and more importantly, it attempts to recreate a portion of contemporary South Korean life out of the burgeoning suicides and plummeting marriages that we read about only in pie charts and data graphs tucked away in a corner of the newspaper. For the diverse setting and freshness it brings, it deserves a chance on our bookshelves.

If I Had Your Face

Author: Frances Cha

Pages: 272

Publisher: Ballantine Books (Random House)

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu