Arts

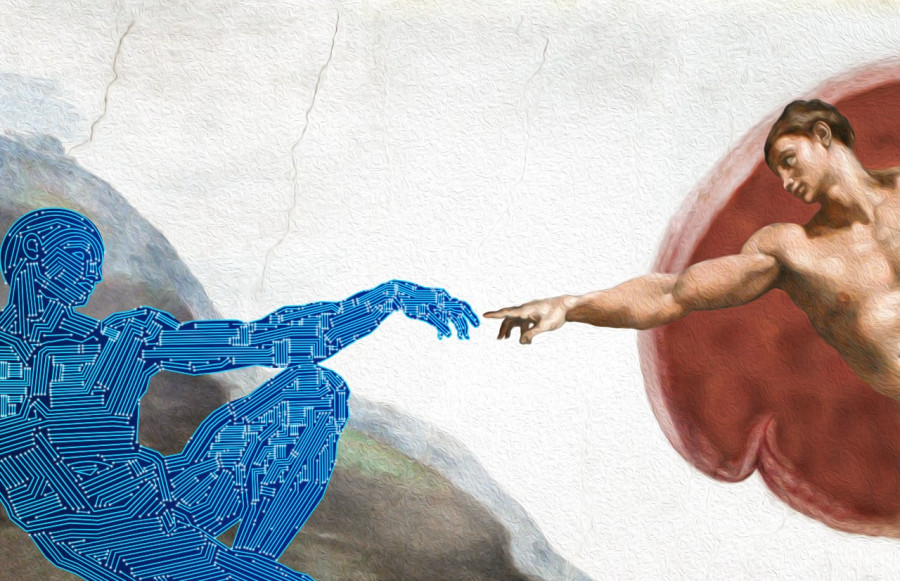

If AI paints a masterpiece, is it still art?

While some see AI as a powerful tool for artistic expression, others argue it lacks originality and emotional depth.

Anish Ghimire

Art is an important form of human expression. For centuries, it has evoked emotions and helped us understand the human psyche in a way no other form of expression has done. In my many conversations with artists, I understand less about their art and more about their minds and the high tide of passion surging in their hearts. If art is so intimate and only draws from personal experiences, can we call AI art real art? Without the most essential ingredient of emotional appeal, will we ever visit an exhibit where only AI art is displayed? The debate goes on.

Pooja Duwal, a visual artist based in Bhaktapur, believes art is a medium through which we communicate our deepest values and aspirations. “Humans are the soul of art,” she says. “Whether the cave paintings of the Stone Age, body art of tribal communities, traditional practices or contemporary style, the common thread is that it exists to bind humans together beyond individual experiences.”

Like Duwal, who cannot imagine art without human intervention, novelist and short-story writer Daphne Kalotay told The Harvard Gazette that AI lacks two main things: insight and experience. These two elements have been specialities of art for centuries.

However, some believe AI and human touch can blend, elevating the art landscape. Architect, photographer and director Pranab Joshi has been working on reviving Nepal’s historical figures and mythical stories through digital art and AI. He believes today's art is all about ideas, concepts, context and impact. “Art has evolved beyond technicality and personal expression,” he says.

Maurizio Cattelan’s famous ‘Banana on a duct tape’, which sold for $6.24 million, is a good example of how concept matters over execution in contemporary art. “The banana alone didn’t sell for millions; it was the idea, the statement and the cultural impact behind it,” he says.

In a similar vein, Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Urinal’ (1917)—a standard porcelain urinal signed ‘R Mutt’ now considered one of the most influential works of modern art, was once shocking and controversial. “Duchamp didn’t paint anything. He simply took a urinal from a hardware shop,” says Joshi. “It became popular because it challenged traditional notions of authorship, creativity, and artistic intent.”

We see the same with AI today. While it may be perceived as a threat to original art, it can be a transformative tool in the art world, enabling artists to explore new creative avenues and redefine traditional artistic processes. “AI and humans together can generate unique visuals, music and narratives. If AI is limited to being used as a tool, then, yes, I would consider AI art to be real art,” says Joshi.

The other issue of discussion is ‘originality’. Can AI generate original content? Based in Parsa, artist Manu Kumar Chaudhary, who reflects cultural aspects from the Tharu community in his works, says AI creates art from existing data. “Unlike humans, AI has no independent thought, emotions or sense of purpose,” he says. Currently, AI cannot be commanded to create something of its own. Duwal also agrees with this.

Since it cannot think independently and relies on sources available on the internet, another issue of ‘copyright’ arises. Duwal raises the issue that although AI can be a tool, it plagiarises artists’ works without due permission, credit or compensation while being presented as an original creative work. “I think the premise of AI as an original creator is dangerous,” she adds. She also says that after a while, AI art can get repetitive as it only builds on existing images.

An example is Kelly McKernan, an American artist, who found their artwork used without permission to train AI models like Stable Diffusion. According to The New Yorker, they noticed AI-generated images mimicking their style and joined a lawsuit against AI companies for using artist’s work without consent. In August 2024, a US District Judge allowed the artists’ copyright claims to proceed, rejecting the defendants’ motions to dismiss. As of February 2025, the case is still ongoing.

Even in such a twisted scenario, Duwal still thinks that AI encourages novice enthusiasts. Someone with a concept can use AI tools to turn vague imaginations into creative visual outputs. “Even so, nothing can beat the human feeling of picking up a brush, mixing colours, and learning through trial and error,” she says. “AI lacks that aspect of human vulnerability.”

Joshi counters this by giving an example of a 2008 sci-fi movie called ‘Wall-E’. In it, we see a very ‘human-like robot’ with emotions who falls in love with another robot. “That robot made us emotional, proving that even something mechanical can evoke deep human feelings if crafted with care. The same applies to AI art,” he says, adding that it’s the artist’s role to infuse meaning, emotions, vulnerability and soul into their work, regardless of the medium they use. For Joshi, AI is just another tool, much like a paintbrush or a camera.

He is also optimistic about the wide usage of AI, as it will likely increase the value of traditional, hand-painted artworks rather than replace them. “When photography was first introduced, many feared it would make portrait painters obsolete. Instead, portrait artists adapted, and their work became more valuable because it carried something photography could not replicate: the human touch, interpretation, and depth of an artist’s perspective,” says Joshi.

Although Chaudhary is sceptical about AI as a sole creator, he says it can save time, boost productivity, and improve artists’ skills. He reminds us that everything has pros and cons, and in this fast-moving age, we need to move according to technology.

The other question that arises is of ‘hard work’. Every artist goes through a painstaking process of mastering their craft—practising for years. Aside from practice, they study and experiment until they reach a point where they are proud of the output. This is one of art’s speciality—the hours and hours of toil behind it. But AI changes all of that. With a few quick prompts, you have yourself an art in front of you. This can be a major challenge for traditional artists to survive in the market.

When asked if AI is a threat to artists, Joshi says, “It can be a threat to those whose work is solely about replicating art styles that are available elsewhere.” He declares unique and one-of-a-kind art styles aren’t endangered. “Copying Picasso’s style won’t make you a Picasso—it would only add more value to Picasso’s legacy. Just like the invention of fire, its impact depends on how we choose to utilise it,” he says.

The debate over AI-generated art is unlikely to reach a definitive conclusion anytime soon. While traditionalists argue that art’s essence lies in human emotion, experience and effort, others see AI as an innovative tool that expands creative possibilities. History is our tutor, showing us that new technologies often challenge existing norms but rarely erase them. Instead, they force artists to adapt and evolve.

Perhaps the question is not whether AI can create art but how artists and audiences engage with it. Will AI remain a mere tool, or will it redefine the very meaning of creativity? Time will tell.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)