Arts

Encounters with beauty and loss

PhotoKTM 5 asks us to engage—to stop, think, change our way of life, and reboot entirely, in the face of a looming climate catastrophe.

Sophia L Pandé

Today, more than ever, we stand at the threshold of an apocalypse. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report last week that gives us a decade (maybe) before the planet warms 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, bringing about extreme changes in weather patterns, precipitating natural disasters that would render the Earth close to unlivable. This unfolding scenario is quite literally on our doorstep. A decade can flash by in the blink of an eye, just as decades have passed as the world has largely ignored increasingly desperate calls for reducing carbon emissions.

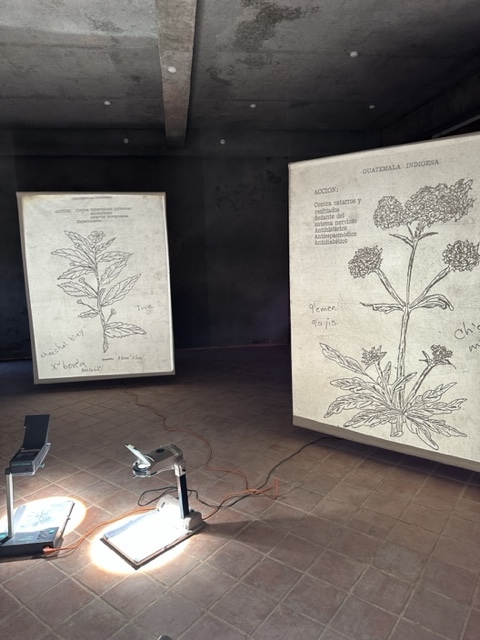

The fifth edition of Photo Kathmandu asks us to engage; to stop, think, change our way of life, and reboot entirely, in the face of this looming catastrophe. It is not didactic, it poses questions, provides both general and specific examples, giving visitors a chance to re-experience slices of the natural world in the heart of a bustling mediaeval city, and a rare opportunity to immerse themselves in alternative futures, some radical, others more pragmatic, a few made particularly beautiful by their compassion and nuanced world view.

The festival uses videos and photography, the chosen medium of documentarians, to highlight the plight of the planet, showcasing poignant vignettes of both the humans and non-humans who inhabit it. Working at a sophisticated nexus of botany, ornithology, technology, anthropology, photography, and methodical research, the exhibits portray the stark realities of the loss of ur-seeds and traditional farming methods due to scientific and technological advances in agriculture (at Gallery MCube), and the devastating impact of treating cattle with Diclofenac, an NSAID used to reduce pain and inflammation in people as well, resulting in a mass poisoning of the vultures or Jatayu, that feed on them (at Namkha). There is a silver lining here, but you must go to the exhibition to properly experience it.

With ‘Chhimeki Chara’ we learn about the enchanting plumage and characteristic trills of our neighbourhood birds, the Black Bulbul, the Alexandrine Parakeet, the little Brown Shrike, most of which are fast losing their habitats as humans displace animals, birds, plants, and trees (in Chyasal but also spread out across the festival routes). At the Aakash Bhairav Temple Exhibition, in Khapinchhen, we are taught, aurally, how to name avians in various languages, to deepen our connection to the environments we live in, and we get a chance to watch people across Nepal speak intimately about the uses of the indigenous plants that grow in their areas. At Patan House, in the Dhaugal neighbourhood, we come face to face with the artefacts of progress that scar our natural landscapes, not always bringing the benefits they promise, a stark contrast to the images of stunning endangered orchids, pinned onto a wall on the street itself, providing an unexpected but welcome burst of marvellous flora against a bleak backdrop of brick and cement.

Changing behaviour takes generations. If we are going to evolve to respect the planet and everything that lives on it and survive climate change, it needs to be now, yesterday even, not in a few years’ time, and it needs to happen en masse, from grassroots to policy level. People have always turned away from the truth when it is too difficult to face, we see it in our government but also in our own civic behaviour as we continue to buy new mobile phones, purchase new vehicles, buy synthetic clothing, build our houses without any attention to the carbon footprint we are creating, or the trail of effluence we are leaving behind.

Nepal may not contribute much to global carbon emissions, but putting out a bonfire fed by wood and plastic today, whatever our traditions, composting our waste, trying to live a life with attention to the community, making way for those who do not have agency, human and non-human, and opening our minds to thought-streams and points of view that are different from our own, are all specific and general ways that we can start bringing about meaningful change from within. Art may be the only vehicle that can truly provide an outlet and platform for conversation that might address all our anger, fears, hopes, and dreams.

The Skin of Chitwan, the biggest exhibit at Photo Kathmandu (at Bahadur Shah Baithak) seeks to do this. It is an immersive, tactile experience that brings the viewer into a space where we experience the degradation of the very soil of a celebrated national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site. With ambient sounds and voices, images and microscopes, the curators and researchers have brought us an unconventional archive from a place of loss and flux—we can make of it what we may, be moved by the violence to nature, the uprooting of the indigenous Tharu people, dismayed that progress has wrought irreparable damage on a way of life, even while bringing relief from endemic diseases like malaria, and providing employment other than back-breaking subsistence agriculture.

Can we build an alternative future that incorporates the magic of science and technology while turning back to our roots and opening ourselves to the wisdom of indigenous knowledge? Can we move away from broad, generalised, mainstream notions of development, forging a unique, rigorous path that incorporates a vertically integrated, grassroots-based sustainability without becoming Luddites and railing against all progress?

The answers are in our own hands, maybe even in our dreams, as long as we stop to think, listen, and above all, to pay attention.

PhotoKTM 5 is on till March 31.

15.12°C Kathmandu

15.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)