Culture & Lifestyle

Ghosts of violence

The Skin of Chitwan highlights the ‘erasure’ of the Tharu community’s indigenous practices.

Sarah Shamim

A brief walk from Patan Darbar Square brings one to the historic Bahadur Shah Baithak. The Baithak’s walls will narrate some previously unheard stories of Nepal’s Chitwan district for the next few weeks. Many sights and sounds of the region are presented in the space, ranging from microscopes that zoom into the region’s soil to photos and audio recordings collected from the residents.

Visual projects about rebuilding relationships with land constitute a significant aspect of photo.circle’s fifth edition of PhotoKTM. The Skin of Chitwan is one such project, subject to particular anticipation. This is developed by photo.circle’s own digital picture archive, Nepal Picture Library (NPL). The Skin of Chitwan aims ‘to reframe our relationship with a place like Chitwan’, according to NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati, the co-founder of photo.circle and director of PhotoKTM.

The PhotoKTM team and participants visited Chitwan in the first week of March 2023. This trip involved a jungle walk guided by a resident of Chitwan who enlightened the team with stories about the trees and temples of the region.

This assessment of anthropogenic activities in Chitwan is transcending the online realm for the first time at PhotoKTM 5. The project stems from a combination of efforts, including research, curation, archiving, and digital development. Several members of NPL and external bodies have worked on this.

Yutsha Dahal joined NPL in 2018 and was involved in the research for the Chitwan project. Her interest in assessing climate change and the Anthropocene as cultural phenomena brought her to Chitwan with the NPL team in 2019.

“You feel a sense of discomfort when you enter the forest because you know of the atrocities that have happened,” said Dahal. She was uncomfortable because the reality of Chitwan differed significantly from what she had grown up believing about the region. She explained that the media and everyday language further some preconceived notions about the region.

For someone who grew up in Nepal, Chitwan is “a tourist destination slash a National Park slash jungle safaris,” said Dahal. In fact, Chitwan is viewed as a good example of wildlife conservation efforts. This narrative overlooks the region’s recent history of deforestation, extinction of species, and displacement of indigenous people. “Chitwan is more than just a place of leisure for the wealthy. Chitwan has a lot of stories that we perhaps haven’t paid attention to,” added Kakshapati.

The project seeks to highlight that the development of Nepal has come with the cost of the lives and health of Chitwan’s original indigenous inhabitants, the Tharu people. Dozers have not only destroyed forested land for modernisation projects but have furthered a harmful erasure of the Tharu community. Traditional knowledge systems and indigenous ideas of the future are neglected. The project highlights that the region’s original inhabitants are not actively consulted when decisions are made about the use of the space.

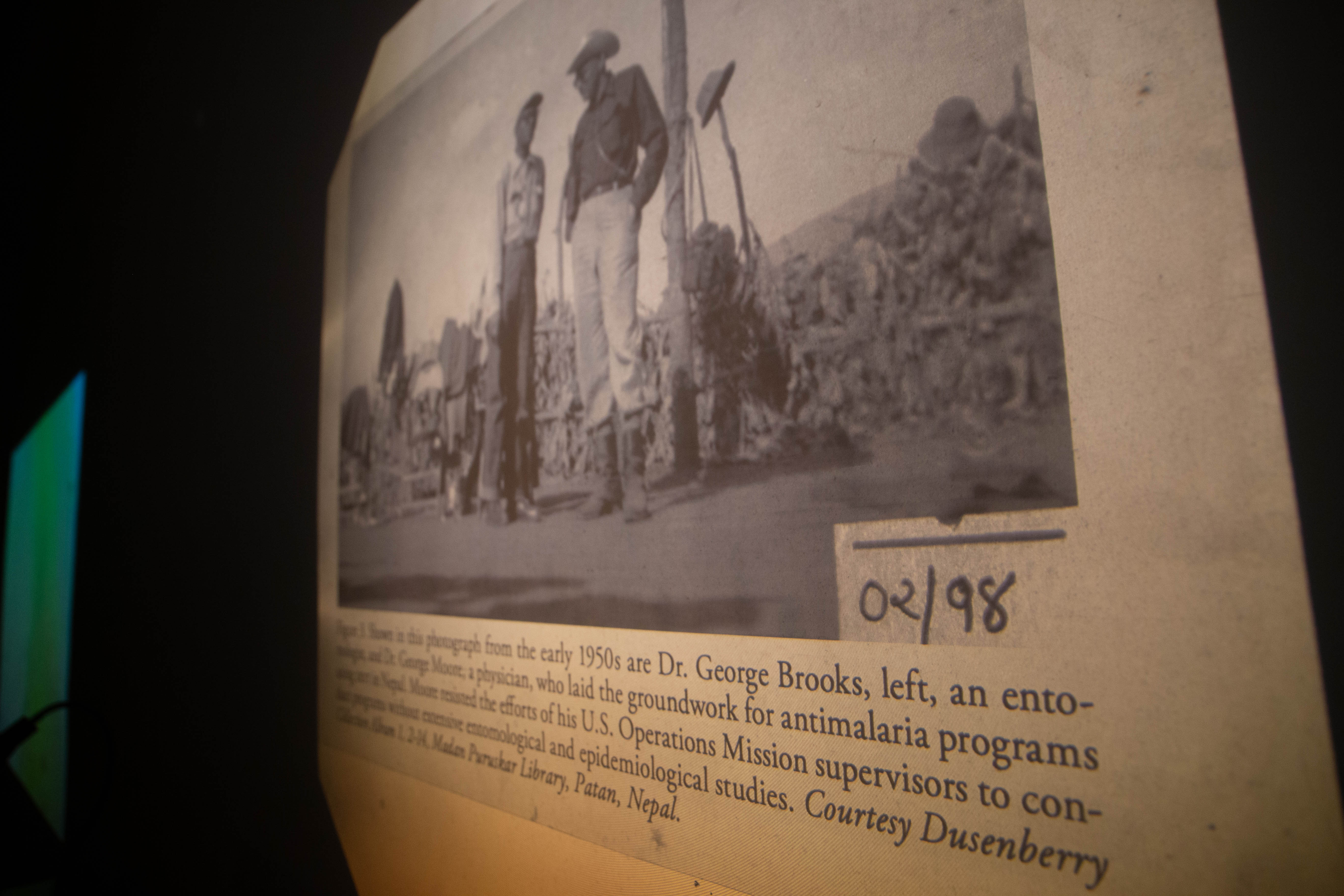

An example of the harm caused to Chitwan and its indigenous inhabitants was the use of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), which according to Dahal, was introduced into the region by US development agencies to combat malaria. This introduction was a product of foreigners seeing Chitwan’s potential for development through an American lens. The Tharus had acquired immunity to malaria in the region, according to Environmental Historian Tom Robertson. Through DDT, malaria was eradicated, and Chitwan’s resources were harnessed for the economic development of Nepal. The chemical did more harm than good for the Tharus as it damaged their health and the environment. Furthermore, because malaria was eradicated and the land was now suitable for being used for agriculture, the upper-caste residents of the hills migrated to Chitwan, displacing the indigenous folks. What started as an anti-malaria campaign escalated into the erasure of the indigenous Tharus.

Dahal mentioned that the NPL team has often referred to the discomfort experienced in Chitwan as “ghosts of violence.” The legacy of injustice lingers in the environment even if the violence is not taking place in the present day. The idea of ghosts is additionally important because the Tharus navigated the landscape by using stories and shrines of gods and ghosts to make sense of their space. The motif of these ghosts is recurrent in the interactive website that keeps The Skin of Chitwan constantly accessible online. Upon scrolling, images and videos of Simal trees accompany the sounds of Chitwan’s gushing wind. The project was not intended to take the form of this website initially. Exhibition Curator Diwas Raja KC explained that it was originally meant to be a physical, sensorial exhibition in 2020. However, coronavirus hit in the middle of the process, and the project materialised as the website, which turned out to be successful.

This website eased the process of curating the physical presentation of The Skin of Chitwan for PhotoKTM 5. The focus of the project has also shifted over the past three years. “The presentation and the choices we made for the website altered the direction of the exhibition. It has become the context and the blueprint,” explained KC. Since the audio and video accompaniments were already created for the website, the process of executing the physical exhibit spanned over 20 days of designing and 12 days of fabrication. The focus of this production involved managing physical screens.

Creating awareness and beginning to reimagine the region is part of NPL’s larger project called Indigenous Pasts, Sustainable Futures. Dahal believes that current science and geography box concepts such as climate change into homogenous categories. However, to truly understand the situation in the future, climate change needs to be reimaged keeping politics in mind. The reorientation of space is easier said than done, according to KC. “Getting the guides in Chitwan to tell stories about the region differently requires a lot of time, patience, and attention. But our minds are on it,” said KC.

The Skin of Chitwan is on display at Bahadur Shah Baithak every day from 11am to 7pm until March 31.

22.12°C Kathmandu

22.12°C Kathmandu