Entertainment

A Ladakhi in the trans-Himalayan nexus

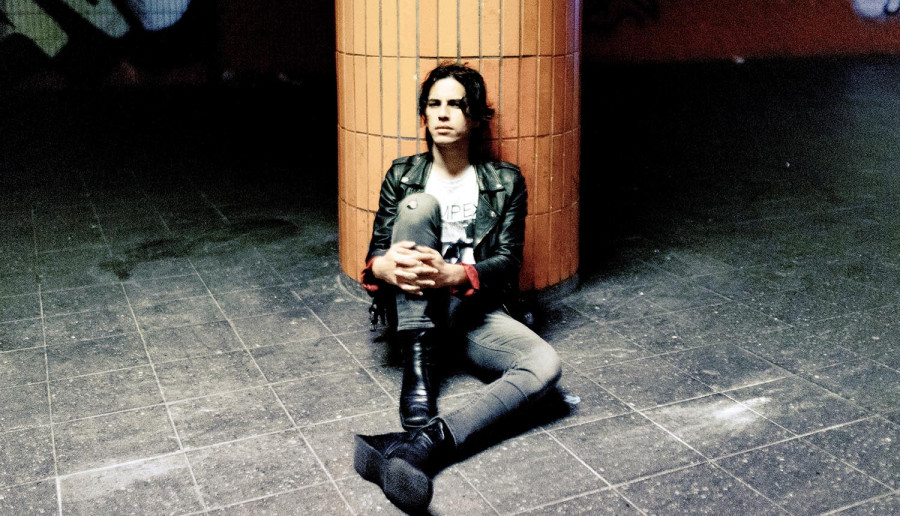

Ruhail Qaisar, a noise musician from Ladakh, draws from intergenerational trauma and the ravages of late-stage capitalism.

Sarah Shamim

Sitting on the balcony of a cafe in Thamel, Ruhail Qaisar deconstructed the abstruseness of handmade instruments. “You get Piezo mics, best for metal surfaces,” he said as he knocked on the cafe’s metal balustrade with his ring, briefly clanging through the metal. “They pick up the sound from the inside.”

This deconstruction soon veered into a conversation about the history of noise music. Qaisar talked about how the Berlin-based band Einstürzende Neubauten began making instruments by hand in the 1980s using stolen construction materials. He explained that this was due to their lack of means to buy instruments. Born in a lower-middle-class house in Ladakh, Qaisar, 28, has related to this struggle, relying on instruments made from found objects as a self-taught noise musician.

His music is a manifestation of personal and political catastrophe. The decay of Ladakh caused by late capitalism, coupled with the trials of intergenerational trauma constitute his defiant sonic performance. On March 11, Qaisar presented his work in Lalitpur with noise musicians from Nepal and the United States.

Qaiser was born to Muslim parents, the first educated generation in Leh, the largest city of India’s union territory, Ladakh. The region’s geography, at the helm of borders with Pakistan and China and has yielded a historical legacy of land disputes and encroachments.

Qaisar did not see a whole lot of technology during his early childhood. He did not grow up seeing many educational institutions. He explains that there was a trend where parents sent their kids abroad to study. Consistent with this, he was sent to a boarding school in Delhi. Around 2010, flash floods hit Ladakh. These floods were destructive to the point where they were considered extreme geologic events in the Himalayan region. After this, he began to see Ladakh transform into a tourist town. During Qaisar’s time as a University student in Delhi, he lost his aunt, Fatima. The loss of an integral community member coupled with the decay in his hometown informed his second album, which he named Fatima. A “requiem for a dead future,” Fatima was released in January 2023. Confusion and chaos translate into the album through a diverse array of tracks, each one so sonically distinct yet thematically interconnected.

Qaisar takes found footage from Ladakh and mutates it using electronic frays and sounds. This is part of Qaiser’s efforts to preserve and repurpose totems that uphold memories of what Ladakh used to be. As the album opens with ‘Fatima’s Poplar’, it is particularly intriguing how Qaisar borrows from English philosopher Nick Land, contextualising and transforming Land’s words based on his own experiences. Another track, ‘The Abandoned Hotels of Zangsti’, relies less on words and philosophy, and more on the chirping of Choglamsar village’s birds that reach a calming yet cautionary crescendo before they quiet down.

Qaiser’s journey as a noise musician was a subversive attempt to break away from the stasis and polished over-curation within the music scene in India’s elite circles. To Qaiser, “mess ups, mistakes, and aberrations hold more power than anything that exists on more commercial terms”. Therefore, he began to connect more with the organic music scenes in Lahore, Bangladesh, and Kathmandu. “I felt like the music there was emerging from a community level rather than through daddy’s studio,” Qaisar said, putting out a cigarette before lighting another.

Through these links, he released his album under Aisha Devi’s Berlin-based record label, Danse Noire. Devi, whose paternal lineage comes from Kathmandu, liaised between Qaisar and Nischal Khadka, who works on curating and combining different audio and visual media within the Himalayan region. “He has been trying to form this trans-Himalayan nexus of artists and I resonated strongly with the idea and motivations. I wanted to do something in Nepal,” said Qaiser.

This resonance brought him to Beers N’ Cheers in Jhamsikhel for an event called ‘Noise Trepanation’. The event’s name was inspired by one of Qaisar’s favourite Concrete Winds songs of the same name. Alternating red and blue lights illuminated the dark space as a niche group of people gathered for the event.

After the event, Qaisar spent the remainder of his time in the valley exploring junkyards and post-earthquake ruins. This is not the first time the artist has been interested in exploring the concept of earthquakes through his art. Last year, he was involved with an industrial band called Xalxala (from the Urdu word ‘Zalzala’ meaning earthquake) where Ladakhi lyrics formed a conjecture with industrial music. This was Qaisar’s segue into noise music. “The idea of that was to try to make music and not make music at the same time. Keep anti-music and music going on at the same time. Like a double mirror expression.”

Qaisar’s time in Kathmandu enabled him to draw a juxtaposition between Kathmandu and Ladakh. Walking through Thamel, a spot curated for tourism, strikes a chord of familiarity within him because it reminds him of home. Both regions once ravaged by natural disasters, were rebuilt on the promise of a blossoming tourism industry. Resultingly, buildings of concrete cement replaced the old architecture in both regions. Qaisar goes as far as to deem the two eras of architecture opposites of one another.

While Qaisar observed Kathmandu’s post-earthquake commercial rebuilding during his visit, he witnessed this process firsthand in Ladakh at the age of ten. He saw the mental headspace of his community deteriorate as commercial tourism rose. Qaisar holds the memory of the phasphun tradition, an old Ladakhi practice where communities took care of each other irrespective of religion. He also recalled the anthropogenic damage done to the region, reminiscing how “things were much purer” during his early childhood. “Rivers weren’t tainted and mountains were clean.”

With his work, Qaisar does not only write an elegy to what Ladakh used to be, but strives to preserve its memory. He is now exploring this in mediums beyond sound. In the past year, he has worked on compiling old home videos into a 30-minute montage. This brings his aspirations of simultaneously preserving and mourning Ladakh into the visual realm.

17.1°C Kathmandu

17.1°C Kathmandu