Entertainment

Verses on vehicles—art or annoyance?

Truck sahitya means different things to different people—some see it as a break to the monotony of long journeys but for others, it’s a nuisance.

Timothy Aryal

Bharat Chalise is a bus driver but he’s better known among his peers as a connoisseur of shayaris—those rhyming couplets in Hindi, Urdu or Nepali that elicit ‘wah wahs’ in response from the audience. In fact, he is something of a anshukavi, able to produce poetry as spontaneously as if they were tears streaming down his face. This is why Chalise is beloved by crew of drivers and conductors.

On a recent afternoon, Chalise sat surrounded by friends, as the bus he drives underwent a facelift at a Jadibuti workshop. When the topic of ‘truck sahitya’ came up, Chalise lit up, then zoned out for an instant and recited these verses: “Gaadi number paisatthi athhasi/ Bharat driver, Saney khalasi,” which translates essentially to: “65-88 is the vehicle number/ Bharat is the driver, and Saney, conductor.” And then one more: “Car car motor car/ dhani bhaye dinthhe haar/ garib chhu didaichhu postcard,” meaning Car car motor car/ if I were rich I’d give you a necklace/ but I’m poor, so I’m giving you a postcard in its place.

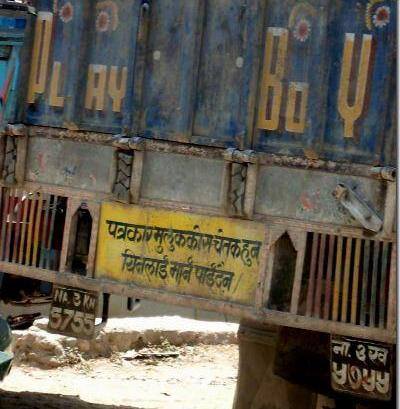

Clearly, Chalise is a special kind of poet, the kind whose verses are emblazoned on the backs of cars, microbuses, buses and trucks. These are often humorous, often poignant, speaking of love, lust and loss.

But though his verses might find their way onto the backs and sides of numerous vehicles, he himself is a staunch opponent of such frivolity.

“It’s nonsense,” he says dismissively. “I know a lot of poetry but I don’t paint them on my bus.”

For Chalise, poetry is something more than a rude couplet meant to elicit a laugh from passersby. Like a true artist, he believes that poetry is something more personal, an expression of the self.

“It’s true that verses can be funny and heart-touching, but they’re something you write on your heart, not on your vehicle,” he says.

Verses on vehicles can cause distractions, especially on long hauls, and could lead to accidents, he says.

“Who will be responsible if a driver gets so lost in the poetry that he causes an accident and kills passengers?” says Chalise. “If you want to write, write on the inside of the vehicle.”

Shiva Prasad Dahal, a mechanic and owner of the Kalika Workshop, seconds Chalise. “A simple phrase like paisa bhusukkai/kanchhi musukkai—money flies when a girl smiles—can distract a driver,” Dahal says. “A driver’s job is to pay attention to the road and get passengers to their destinations on time.”

And yet, Dahal goes on to display some poetry written on a neglected board that Painter Bhanja, a painter at the Kalika Workshop, was once ordered to transfer onto a bus.

“Gori pani kali bhaichhe/ Koshi pari ko dhulo udera/ Duniya ko mutu jalchha/ 7072 gudera,” reads the board, ‘Even a fair girl has turned dark, thanks to the powdery dust from across Koshi/ several hearts are broken, just by seeing 7072 rolling.’ Everyone bursts into laughter.

Decorating vehicles with verses of poetry is a popular trend across South Asia. Quirky one-liners supporting or condemning political parties are ubiquitous on Indian vehicles and Pakistan’s truck art is famed for its creativity and eye-popping colours. Similarly in Nepal, truck poetry—popularly known as ‘truck sahitya’—has become a literary trend, according to Netra Atom, a professor of literature at Tribhuvan University.

Truck sahitya has even spawned a magazine—Bus Sahitya—and a book—Trucksahitya: Sankalit sirjanaharu—that compiles hundreds of verses from the bodies of buses and trucks, edited by journalist Subida Guragain.

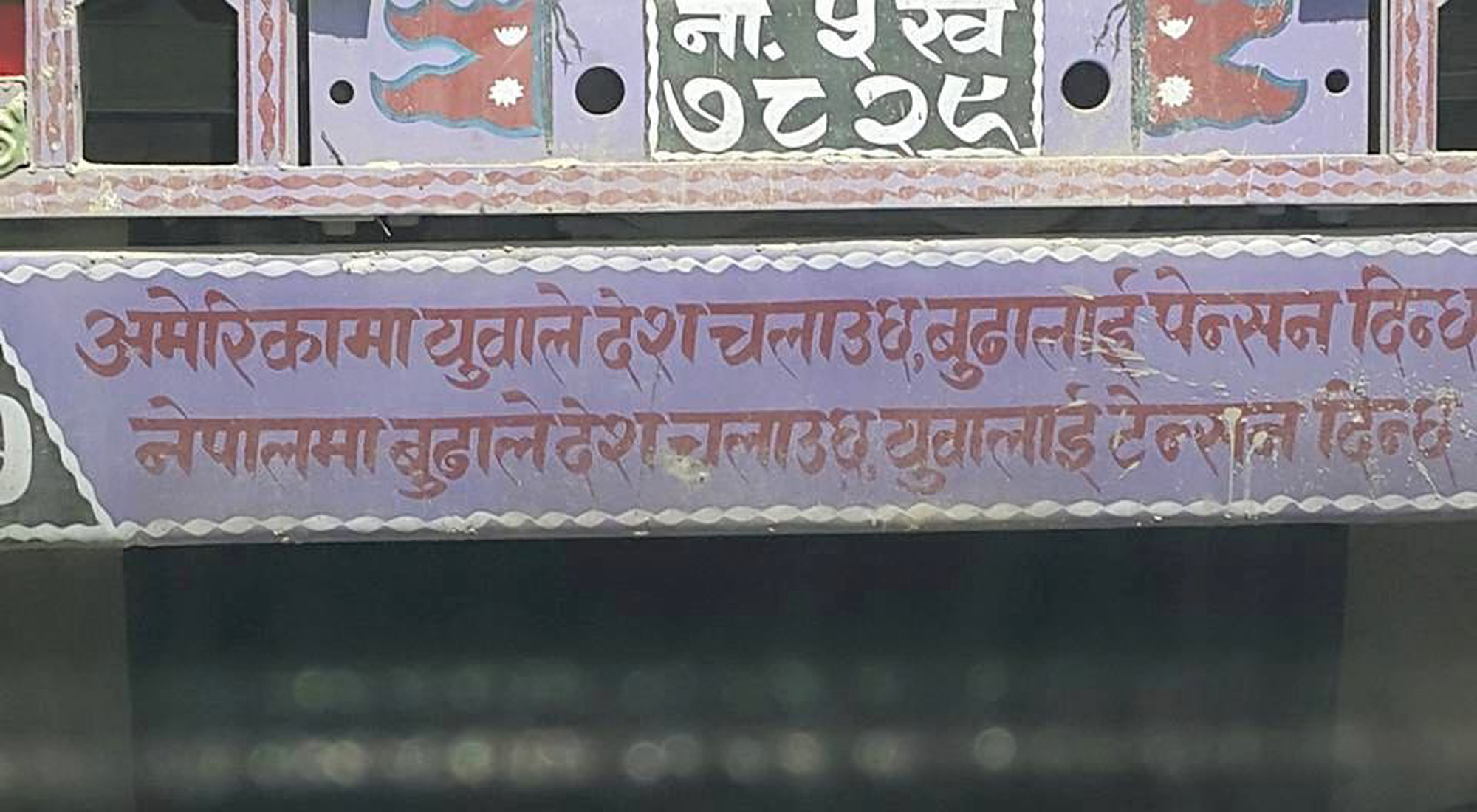

“I decided to compile these verses because of the diverse views they represent,” says Guragain. “The verses capture the general atmosphere of the country and what working class people talk about.”

The concept of the book came to Guragain in 2000, when he was travelling from Itahari to Kathmandu. The Maoist insurgency was at its peak and the police were inspecting vehicles, leading to a traffic jam that stretched a few kilometres. Bored, Guragain started walking, looking at the backs of buses and trucks. That was when he saw the verse that he calls his favourite till date:

“Himal chha, pahad chha, bibhinna taal chha/ Buddha janmeko desh ma buddhi ko anikal chha.”

The verse essentially translates to: “Snowy peaks, mountains, and numerous lakes abound/ But in the land of the Buddha, wisdom is nowhere to be found.”

“This hit me hard,” says Guragain. “All truck poetry in general is quirky, but this one was wise and thought-provoking.”

Om Karmacharya, a Banepa-based painter who has been painting poetry for a decade, says that the nature of the poem depends on the mood and temperament of drivers. While many drivers come to him with their own verses, others discuss their ideas with him and they come up with a verse together, one that is “interesting or sad or however the drivers want it to be.” While many painters do as the drivers order, there are a few who keep a poetry notebook of their own.

Truck poetry can revolve around anything, from nationalism to love. Every so often, debates arise across social media, and on other online portals, regarding whether truck literature is good or bad.

Some women’s rights activists have even argued that all truck poetry should be taken down as they’re often misogynistic.

“Truck poetry is a reflection of our society, there’s no denying that,” says Guragain. “While there are verses that are downright misogynistic, there are also those that advocate for the rights of women. To say all truck poetry must be erased is nonsense. We live in a country that guarantees freedom of expression, and to know the collective expression of our society, what’s better than truck poetry?”

While driver Chalise opposes truck literature, other drivers, such as Binod Rai and Devendra Shrestha, who drive from Butwal to Kathmandu, say that truck poetry is just fun, nothing else.

“I don’t think a simple poem written on a bus can cause accidents,” says Rai. “I love reading poems during long journeys. It makes for rare fun to read a good one.”

9.8°C Kathmandu

9.8°C Kathmandu