Entertainment

Art and Process

The current exhibition at the Siddhartha Art Gallery is a joint one presenting the works of Maureen Drdak and Youdhisthir Maharjan, both of whom are working in mixed media, albeit using very different forms

Curating a joint exhibition is tricky. One has to take in and compare the works of two usually very different artists and try to find complements, parallels, overlaps, or blatantly underscore contrasts. Drdak and Maharjan’s current exhibition is an example of a rare, serendipitous phenomenon where both bodies of work inform and complement each other—both in form and in the processes as well.

Walking into the exhibition space, the first floor is taken up by Maureen Drdak’s exquisite works on paper and in repoussé painting—the latter a process and art form that the artist perfected during her 2011-2012 tenure as a Fulbright Scholar here in Nepal, working under the guidance of master repoussé artist Rabindra Singh Shrestha, who comes from a long line of famed Patan based artisans dating back to the 16th Century.

Drdak’s large scale, indeed epically scaled, repoussé works were put on display at the second Kathmandu International Art Festival (KIAF) in 2012, a culmination of her particular brand of working in the classical repoussé style as trained by her guru, Rabindra Shrestha, but incorporating a painterly method of layering in other media, as one would on a canvas, resulting in a highly original amalgam of Western and Eastern styles and iconography.

The walls of the ground floor are programmed to highlight her Lacuna and Weeping Banyan Study series’ on handmade paper, the third wall holds three of her smaller repoussé works—the only ones she was able to pack and carry for this impromptu exhibition of her work, in what is a brief visit to Nepal.

While Drdak’s work in Nepal is very much synonymous with her grappling with and mastering the immensely physically taxing repoussé form—which entails hammering a metal sheet from the reverse side in order to create a relief on the opposite surface—her delicate graphite pencil works on paper are an exquisite but oddly analogous counterpoint to the more overtly physical pieces on display—exhibiting a range that is essential to any bonafide artist, underscoring that the fine arts do indeed require a certain finesse of the hand and of the eye.

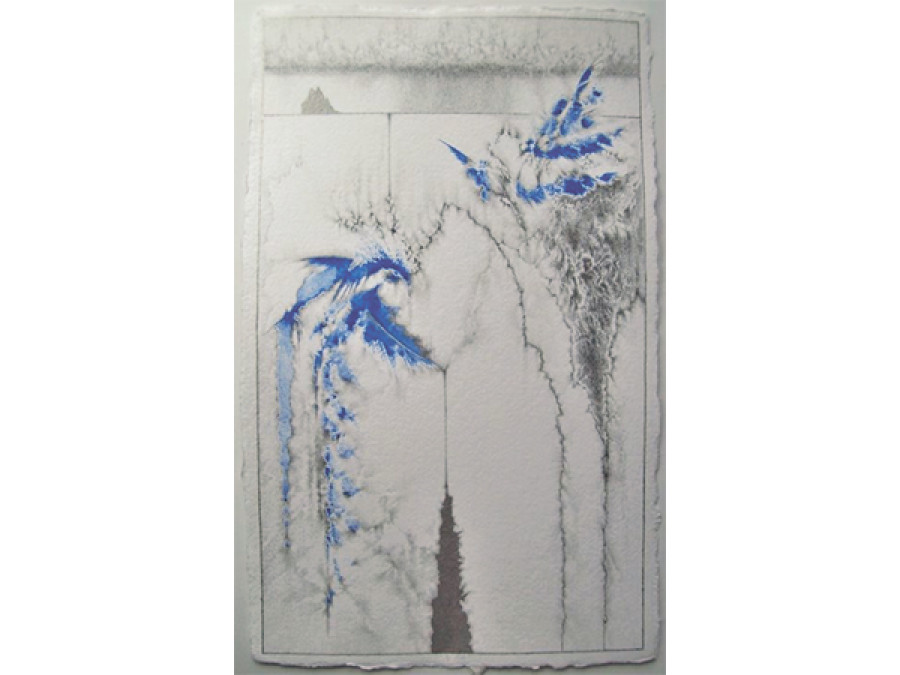

Made on a special handmade paper by the company Twinrocker, which works with artists to their specifications, the Lacuna series which consists of five exquisite works, and Weeping Banyan Study (three studies for another series of repoussé paintings, two of which are on display in the show) are elaborate, extraordinarily fine drawings made with lines from honed graphite pencil, ground lapis lazuli, and palladium, which is essentially ground platinum.

Each of these intricate drawings are painstakingly created by the artist in between her repoussé pieces, serving as a visual contrast to the physicality of the metalwork paintings, and demanding extreme attention from the viewer. While the pieces seem and indeed formally are abstract works made via a contemplative, meditative process, their

surfaces and textures reward repeat viewing, and indeed evoke, particularly in the case of Lacuna 1, almost landscape like depths within its physically small, but psychologically vast surface—an extremely intuitive observation made by Youdhisthir Maharjan during my conversation with Drdak.

There is a lot of contemplation of surfaces in art, with the words ‘contemplation’ and ‘surface’ being particularly operative when speaking of the works of Youdhisthir Maharjan, a young United States trained fine artist whose works are hyper conceptual and yet share the same extreme meditative process that is required to execute Drdak’s drawings.

Maharjan’s pieces, exhibited on the second and third floors of the Siddhartha Art Gallery, are striking in their conceptual sophistication and originality; there is no facile self-indulgence here. The middle floor of the gallery is covered in works that are based on pages taken from books—titled Love, Quest for Human Happiness, A Report on a Thing and my personal favourite, Understanding Our Dreams. Each piece is a rumination on splitting language from visual perception.

Maharjan is fascinated with books and with language, but he does not read. Instead, loving the materiality of books, he derives an algorithm for each page he extracts, using this algorithm to rigorously blot out every single letter on the page except the ‘I” for instance, creating a visual rift between the title and the page itself—which becomes another kind of abstraction based on the algorithm, therefore “freeing language from its enslavement to meaning”—in the artist’s own words.

The repetition inherent in such a process (imagine sitting down in front of a leaf out of a book and meticulously, neatly blotting out every letter) is revealing of a certain kind of artistic passion, and of the muscular rigour (in Drdak’s words) that is necessary to make any kind of art truly worth repeated viewing.

Both Drdak and Maharjan share a disciplined ability to talk articulately about their work from inception to finish, sometimes an incredibly frustrating exercise while speaking to other Nepali artists whom, while they might make exceptional, incredibly complex works, when hard pressed, often cannot identify the origins of the symbolism and iconography they employ, are unable to defend their choices of media, and frequently leave the academic part of research out, even while their technical skill is clearly above par.

Artists embark on diversifying their horizons and tool-kits so that they can explore their own limitations, constantly learning and adapting their processes to remain relevant; both to themselves and to the world around them. Drdak and Maharjan’s works are evidence of such experimentation, backed up by extraordinary technical skill and thinking, searching minds.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu