Culture & Lifestyle

A gallery of memories

‘To All the Women Who Came Before Me’ by Priyanka Singh Maharjan invites us to notice the quiet, uncelebrated work of ordinary women.

Aarya Chand

Walking into Priyanka Singh Maharjan’s exhibition ‘To All the Women Who Came Before Me,’ I didn’t expect to be confronted with so many quiet, unspoken truths about the women in my life. The exhibition, held in a modest but thoughtfully arranged space, is a tribute to the labour, love, and resilience of the women in Maharjan’s family and community. Also to the women who worked in fields, wove shawls, raised children, and, in the case of her great-grandmother, taught children to read at a time when education was not a priority for girls.

The first artwork that caught my eye, ‘My mother’s harvest’, stopped me in my tracks. There’s something deeply poetic about this piece, which is an intricate blend of graphite sketches and watercolour life. The canvas presents a dense garden of black-and-white vegetables, textured and detailed with such patience that it almost slows down time. Within this grayscale jungle, women, rendered in soft, warm colours, move through their labour. Their bodies bend, carry, and gather. They are mid-task, mid-life. It reminded me of my grandmother’s hands: always busy, always knowing.

But what lingered with me most was the onion. Unlike the maise or leaves, the onion sits firmly in the soil, painted in colour: purplish, quietly bold. It’s the only vegetable allowed this honour. I don’t know the artist personally, but I found myself projecting: maybe the onion was her grandmother’s favourite? Or maybe the artist herself loves it? I laughed to myself thinking, here I go, turning the onion into a symbol of generational taste or buried affection; classic psych major behaviour.

Still, I can’t help but feel the onion is more than a root. It’s a memory bulb. Layers of meals and care, tears and texture. Isn’t that what art is for? A place where we bring ourselves, even if it’s not about us. Where our projections become a way of loving something or someone, we haven’t met.

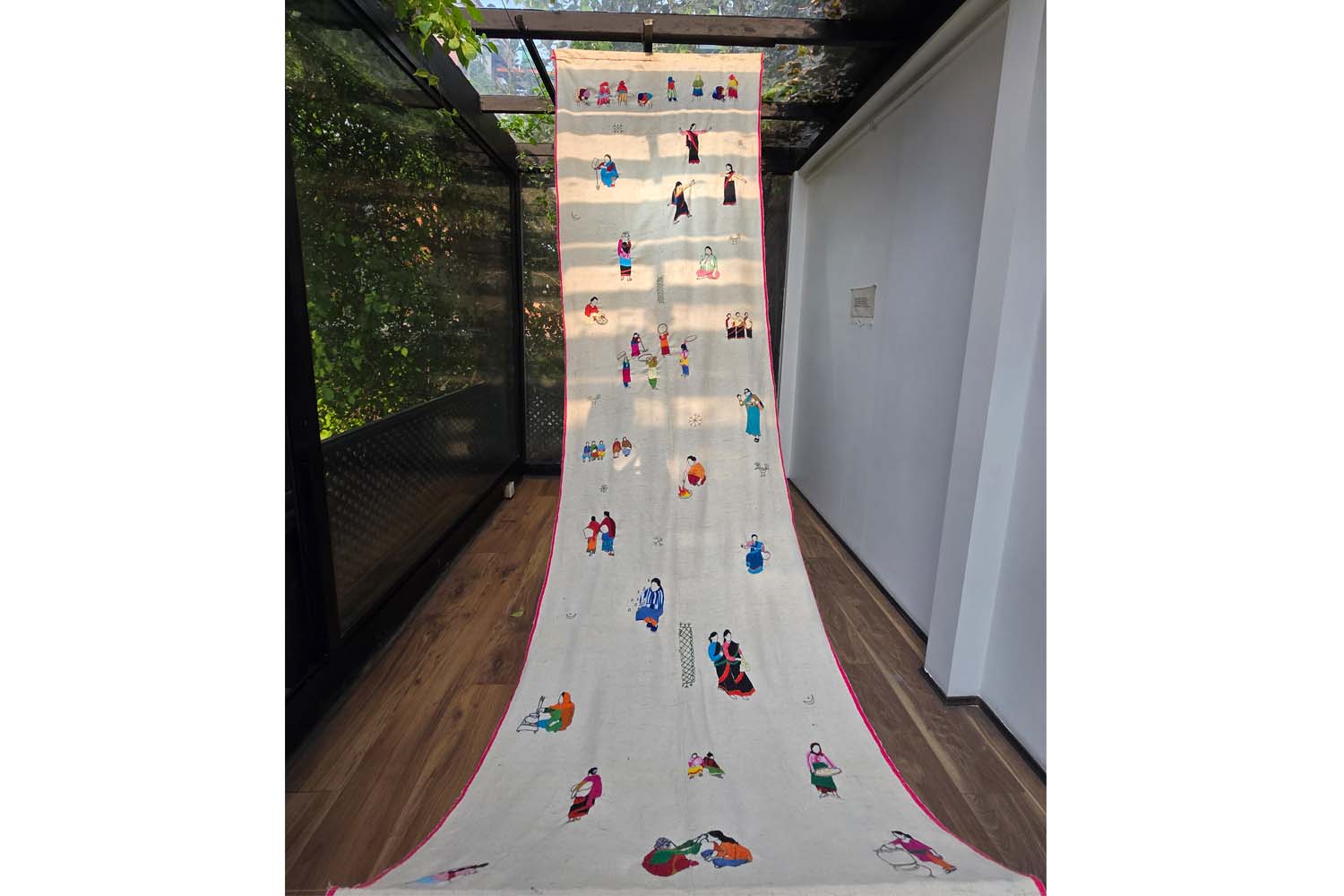

The intimacy of each artwork resonated with me most throughout the exhibition. The pieces are not loud or grandiose; they are deliberate, careful, like the hands that made them. Fabric woven by her Bajey Maa (maternal grandmother) serves as the canvas for embroidered scenes: women tending to crops, hands gripping tools, the curve of a back bent over a loom. The stitches are dense in some places, sparse in others, as if mimicking the uneven rhythms of women’s lives. One piece, a silhouette of her grandmother stitched in thread, is accompanied by a letter. It reads:

‘‘Dear Panga Aji, I hope you are getting to live a good life wherever you are. I am Priyanka, your second son Buddhi Lal’s granddaughter, Umesh’s daughter. I am writing because it’s been a while I have been wanting to. I have never met you but have always admired your strength and resilience.’’

Reading those words, I felt a pang of something I couldn’t quite name. My own grandmother died when I was in class two. Our time together was short, just a few months of my life, but I’ve held onto the certainty that she loved me fiercely. Unlike Maharjan, though, I never got to hear stories about her life, her struggles, or the small joys she might have cherished. Standing there, I wondered: what did her hands do? What did she care about? Did she, like Panga Aji, find solace in books, or was her life entirely bound by labour?

Maharjan’s work doesn’t romanticise these women. It doesn’t turn their toil into something noble or picturesque. Instead, it simply says: Look. This is what they did. This is how they lived.

In one corner, a series of embroidered panels show the same woman in different stages of her day: cooking, weaving, resting with a book. The repetition is deliberate. This is not a singular moment of artistic inspiration; it is the cyclical reality of women’s work.

In the same letter she writes to her great-grandmother Panga Aji, ‘Even as a child, I knew women in our family weren't sent to school because, we are Jyapus. You know how Jyapus are,’ the words heavy with history. Her letter reveals the quiet injustice of their community’s past, how education was deemed unnecessary for girls as they were expected to labor in fields, how Panga Aji became an accidental revolutionary simply by clinging to literacy in an orphanage after losing her parents.

The Jyapu women in her artworks carry this duality in their bent backs and skilled hands: bound by tradition yet resilient within it, their worth measured in harvests and handiwork rather than certificates. Priyanka’s stitches seem to ask—how many brilliant minds were lost to this ‘way of life,’ and what extraordinary women like Panga Aji had to become just to preserve something as basic as reading?

Moving to the next hall, I found myself pausing again: this time in front of a constellation of photographs. They weren’t arranged in any rigid sequence, yet they flowed like a shared memory across the wall. Each photo had that unmistakable texture of old prints: slight blurs, the bold flash of a point-and-shoot camera, and the candidness of life not posed for Instagram but captured in the middle of living.

The women in these photographs cook, gather, farm, dance, and laugh. Some are seated in matching uniforms; others squat in courtyards, cutting vegetables or chatting mid-task. There’s a raw kind of intimacy here: something I can only describe as familiarity without needing to know the names. The kind of photos you'd find buried in an old family album, passed from mother to daughter, wrapped in a scarf with the scent of mustard oil or incense.

The exhibition also includes collaborative pieces, where women from her community have added their own stitches to the fabric. Maharjan explains: ‘‘To embroider, other than the literal act of sewing patterns onto fabric, also means to add exaggerated details to stories to make them more interesting. To embroider means to gossip or to loiter over ‘less important’ details.’’ These details: the food they grew and how they held a needle, make the work feel alive. It’s not a historical record; it’s a conversation.

What stayed with me long after I left was the quiet insistence of the exhibition: that these lives mattered, not because they were extraordinary, but because they were ordinary. Women like my grandmother, Maharjan’s Panga Aji, and countless others lived in ways that were never documented or celebrated. Their labour was expected, their sacrifices assumed. But here, in this space, their hands are remembered.

I left thinking about the gaps in my own family’s stories. Maharjan’s work didn’t give me answers about my grandmother, but it made me ask questions. If she’d had the time, what would she have embroidered? What would she have wanted me to know about her?

‘To All the Women Who Came Before Me’ is not just an exhibition; it’s an invitation. To notice. To remember. To ask. And perhaps, to stitch our fragments of history back together.

To All The Women Who Came Before Me

Where: Dalaila Art Space, Thamel

When: Till 31 May

Time: 11:00 am to 7:00 pm

Entry: Free

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu