Culture & Lifestyle

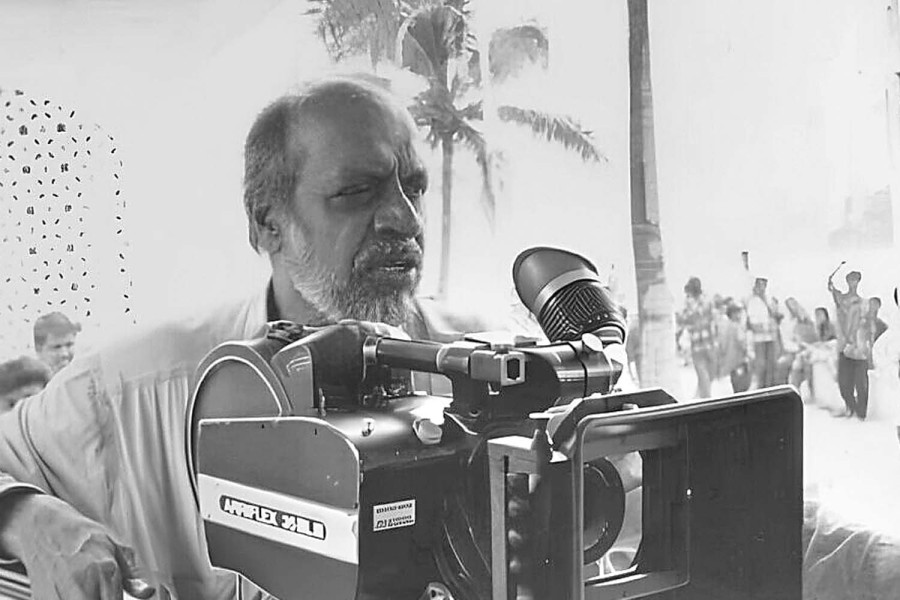

Shyam Benegal: A man so tall he touched the sky

Benegal's vast cinematic canvas encompasses a rich diversity of subjects that move across time, history and geographic location.

Shohini Ghosh

When Shyam Benegal passed away on December 23, 2024, he left behind a legacy of 24 feature films, about seventy documentaries and a large corpus of short films. Notwithstanding his prolific output of which a sizeable number of films are canonical, the true measure of Benegal’s accomplishments transcend quantification.

He was a towering figure who carried fame lightly on his shoulders. He won innumerable national and international awards; held important positions in film schools (like FTII in Pune and AJK MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia) and institutions like the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) and, while continuing to make films, was one of the most productive members of the Rajya Sabha (2006-2012).

In January 2016, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) set up the Shyam Benegal Committee to study global best practices and re-work the rules and regulations of censorship. Submitted in April 2016, the Benegal Committee Report made the radical recommendation that while the CBFC would have the right to certify films, it would not have the power to make cuts.

Needless to say, the recommendations of the report are yet to be implemented. When in 2014, the Supreme Court of India overturned the 2009 Delhi High Court decision on decriminalising homosexuality, Benegal who believed that justice and law were not always on the same side, was one of the first to file a curative petition. He was a riveting conversationalist possessing an encyclopaedic knowledge of history, politics, religion and philosophy. A doer and a visionary, Benegal was a man who, as we say in Bengali, touched the sky.

At the age of six, Benegal had decided to be a filmmaker. He had been captivated by a film called The Cat People (Jacques Tourneur, 1942) a B-grade Hollywood horror film in which people metamorphosed into cats. How wonderous to be able to create worlds that did not exist, thought the young boy.

At the age of twelve, he started his own world-making by using his father’s 16mm silent Paillard Bolex camera. He cast his cousins and members of the extended family to create a film in which a little boy gets lost and the entire family goes in search of him. During the process he discovered the magic of trick cinematography that helped create motion in reverse and have people diving out of the water!

The 1950s was an exciting time for world cinema. The young film enthusiast kept up with the films of Lindsey Anderson in the UK, Akira Kurosawa in Japan and the Italian Neo-Realists by reading the Penguin Film Review that his brother subscribed to. The first edition of The Technique of Film Editing by Karel Reisz, which he read over and over again, became his personal Bible.

His cousin Guru Dutt was an inspirational presence, first as a dancer in Uday Shankar’s school in Almora and then as a filmmaker who made his first film Baazi (The Gamble,1951) at the age of twenty-five. But the most profound influence awaited him in Calcutta. Benegal was the captain of his state swimming team.

In 1956, he visited Calcutta with his team to participate in the national swimming championship. His uncle, who was a commercial artist working in the city, asked him to go and see a film called Pather Panchali (The Song of the Little Road, 1955) by a new director, Satyajit Ray.

When Benegal saw the film, he felt that his mind had exploded. He was wonderstruck that such an extraordinary film could rest on a storyline so slight. He returned every day to watch the film as many times as he could. At the end of each screening, he felt he had experienced something momentous.

“So Ray instantly became my God at that stage” he would later recall.

Born in 1934, Benegal grew up during the early years of India’s independence, a time of great hope and optimism. But when he started making films in the seventies, the Nehruvian dream was in crisis as unresolved conflicts of this vision began to assail Indian democracy. The conflicts and contradictions that beset the fractured condition of Indian modernity were to become abiding themes in Benegal’s films.

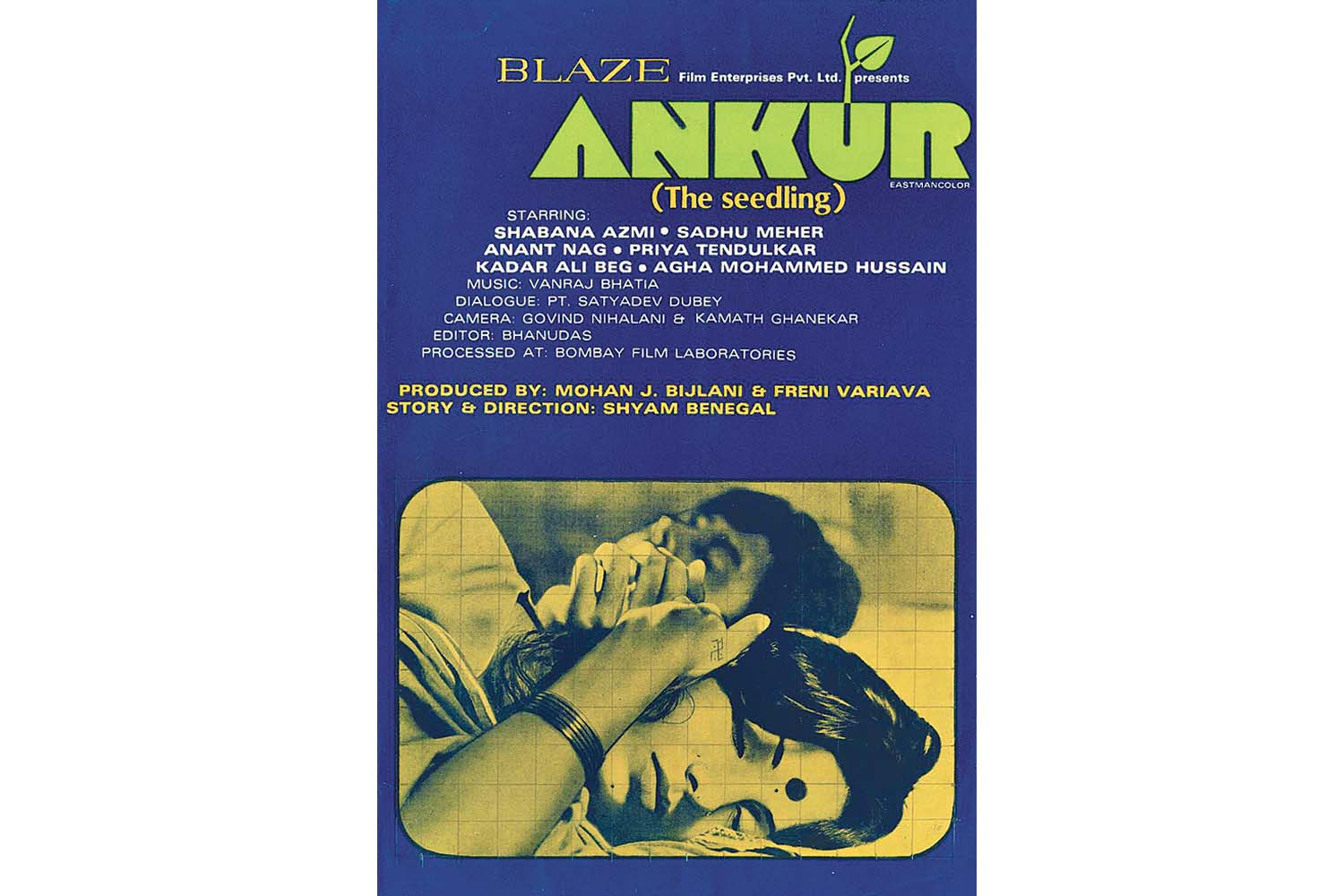

In the early 1970s, he left a successful career in advertising to enter the risky business of filmmaking. He had started writing the script of what would eventually become Ankur when he was in college. He wrote and re-wrote the script for twenty years till he managed to find a producer for the film.

Set in rural Andhra Pradesh, Ankur tells the story about the decline of feudalism and a changing social world through the relationship between the Dalit woman Lakshmi (Shabana Azmi) and the city-educated Suraj (Anant Nag), an upper caste landlord. The educated upper caste man who is quick to initiate sexual relations with Dalit women but is equally quick to disown, retreat or betray in a crisis, is a recurring figure in Benegal films.

Preoccupied with multi-starrers, the Bombay film industry had little interest in the kind of film Benegal aspired to make. Not one to be discouraged, Benegal persuaded an advertising distributor to produce the film. He hired debutant actors, a technical crew that was new to feature filmmaking and made a film that rejected all standard conventions of Bombay cinema.

Released in 1973, Ankur (The Seedling, 1975) inaugurated a new cinematic sensibility. Having watched the film, before its release, Satyajit Ray asked Benegal what he wished for his film. Benegal said he would be happy if the film ran for all three days of the weekend. Ray said that Ankur would run for much more than that and it did.

The rural trilogy started by Ankur was completed by Nishant (Nights End,1975) and Manthan (The Churning,1976). All three films defined the contours of India’s most significant film movement – the Indian New Wave. With the rural trilogy and Bhumika (The Role, 1977) based on the autobiography of the Marathi actress Hansa Wadkar, Benegal’s other extraordinary feat was to create a parallel industry of actors, screenwriters, cinematographers, music composers and producers.

Actors like Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil and Naseeruddin Shah are Benegal’s “discoveries” while Anant Nag, Sadhu Meher and Kulbhushan Kharbanda shot into prominence for their roles in Benegal films. He introduced Vijay Tendulkar as a scriptwriter and Govind Nihalani as a cinematographer. With Benegal’s films, Vanraj Bhatia’s fame as a music composer reached new heights of recognition.

Later, the talented Shyama Zaidi would gain prominence as a screenwriter through her collaborations with Benegal. How did you go about finding these new actors? I had once asked him in an interview.

“In the most conventional way!” he replied. His first choice for Ankur’s female lead was Waheeda Rehman who was known to his family. She turned the role down. He then approached Sarada who won a National Award for her role in Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Swayamvaram (1972). Sarada was keen but her partner refused.

His third choice was Aparna Sen, who was not yet a filmmaker but an extremely successful actress in Bengal. Sen said she would not do justice to the film because she was not good with language and accents. That’s when one of his assistants suggested the name of Shabana Azmi, a recent FTII graduate. When he met her, he knew he had found his female lead. He not only offered her the role in Ankur but also one in his next film. Azmi was incredulous but that’s the way it turned out.

One of the first people Benegal showed Ankur to was Satyajit Ray. He lauded the film – especially the performance of Azmi – while expressing two reservations. The first was about love quadrangles. As a strong believer in geometry as a guiding principle in art and a proponent of the triangle, Ray advised Benegal to avoid quadrangles in the future.

Thankfully, Benegal disagreed and proceeded to make several excellent films with compelling quadrangles. Ray’s second observation was that Benegal had not been even-handed with his characters and had taken sides. Ray felt that the moment one starts off painting one’s characters as heroes and villains, the humanity inherent in the story dies. This was an observation Benegal would always remember.

Shyam Benegal’s vast cinematic canvas encompasses a rich diversity of subjects that move across time, history and geographic location. He explores marginal cultures in films like Aarohan (The Share Cropper, 1982), Susman (The Essence/1986) and Trikal. Films like Ankur, Manthan, Bhumika, Mandi and Hari-Bhari (Fertility/2000), Sardari Begum (1991) Maamo (1994) and Zubeidaa, (2001 engage with women’s marginality and their resistance.

He mapped significant moments in Indian history in films like Nishant that was inspired by the Communist-backed Telangana peasant revolt; Junoon (The Obsession,1978) about an Indo-Anglian family caught in the turbulence of the1857 uprising; The Making of the Mahatma (1996) about Gandhi’s early life and Netaji Subhash Candra Bose: The Forgotten Hero about events that led to the formation of the Azad Hind Fauj.

Sadly, Benegal’s last film Mujib: The Making of a Nation (2023) about the birth of Bangladesh falls short of his own standards and is driven not by a robust engagement with history but with the political narrative of the Sheikh Hasina led Awami League government.

Benegal’s cinematic repertoire is replete with formal experimentations. In Kalyug, (The Machine Age/1980) he recast the epic story of The Mahabharata as a secularised contemporary parable wresting it away from the domain of the mythological. It had been his long-standing desire to serialise The Mahabharat for Doordarshan but when the project went to someone else, he made the 53-episode Bharat Ek Khoj (1988) based on Nehru’s Discovery of India setting a new bench-mark for Indian Television.

Published in special arrangement with TheWire.in

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu