Culture & Lifestyle

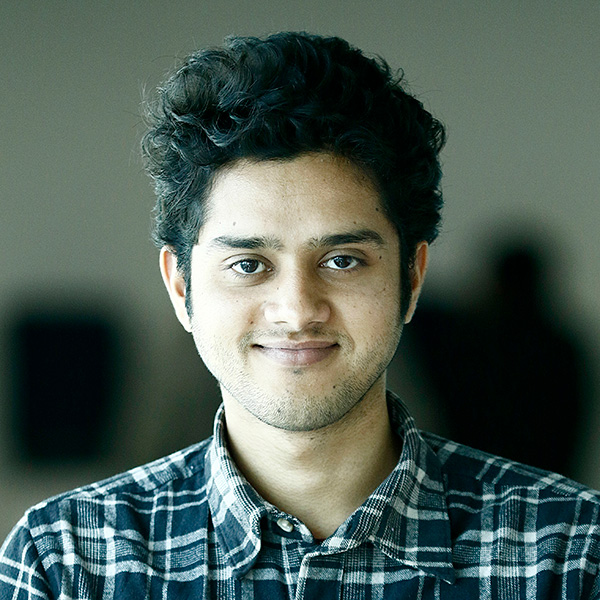

The rhythm of the script: Dev Neupane’s sound sense

Neupane is one of the few people—if not the only one—in Nepal devoted to the art of theatrical sound design. What makes him tick?

Timothy Aryal

A good theatrical sound design doesn’t call attention to itself. It enhances what’s happening on the stage—the emotions, the mood, the atmosphere. It often goes unnoticed, as do several backstage works crucial to a play’s success. “Sound design is a stepchild,” as a reviewer once wrote, “neglected at best, abused at worst”.

“Imagine you’re riding a boat in a lake at a scenic landscape,” says Dev Neupane, over the phone from Pokhara, as he walks the Post through the essentials of good theatrical sound design. “You’re more likely focused on the surrounding scenery, hardly aware you’re on the water. That’s what good sound design does in a play—it’s present without drawing attention to itself.”

Neupane has been designing sound for theatre for about 17 years now and is one of the few people—if not the only one—in Nepal devoted to the art of theatrical sound design. He has designed the soundscape for over 25 plays so far—from 2007’s ‘Banki Ujyalo’, the Nepali adaptation of Girish Karnad’s ‘Anju Mallige’, to Yug Pathak’s feminist ‘Yuma’, and from the existentialist ‘Kafka—Ek Adhyaya’ to Kumar Nagarkoti’s surreal ‘Bathtub’. His latest project, Kedar Shrestha’s ‘Dhukdhuki 72 Megahertz’, is currently on stage at Mandala Theatre until December 1.

Neupane’s craftsmanship is evident in ‘Dhukdhuki’, which explores the emotional journey a couple goes through during the conception of their child. The play’s sound design begins before the audience even enters the theatre, with the timeless song ‘Sachi Rakhu Jasto Lagchha’ from Tulsi Ghimire’s 1993 drama ‘Dui Thopa Aansu’ reverberating through the air. Once inside, the audience is greeted by the soft, improvised notes of the famous nursery rhyme ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’. In this intimate yet universal choice of music, the rhyme emphasises the bond between a mother and her unborn child. Beyond a few sporadic moments of stock music, the play also features recorded songs and aalaps sung by the emerging singer Smarika Phuyal. These sounds, seamlessly integrated into the narrative, create an ethereal atmosphere. Combined with the passionate performances of Menuka Pradhan and Karma, the play becomes an immersive experience.

“Because the play focuses on the maternal psyche, I told the director I would design the sound to reflect the emotions of both the mother and the child,” Neupane explains. “There’s an invisible connection between them, so I used a lot of deep, bass-heavy sounds to emphasise that bond.”

Neupane’s approach to sound design is thorough and methodical. Every script has its own rhythm and it should be dealt with accordingly, he says. “At first, I skim through the script to get a sense of its theme. Then, I read it again from a sound designer’s perspective,” he says. “I consider how the sound architecture fits into the play and how it can enhance the characters’ emotions.”

Putting together a play is a collective process and Neupane understands this as well as anyone. “I sit down with the director to understand their vision. I also consult with the set, costume, and lighting designers, and most importantly, the actors, to understand the emotions they’re trying to convey and how sound can elevate those feelings.”

Once the team has aligned on the emotional tone of the play, Neupane decides whether to use recorded or stock music, depending on the available budget. Once the music timeline is set, it’s tested during rehearsals.

In Nepali theatre, sound design often doesn’t receive the attention it deserves. Shrestha, the director of ‘Dhukdhuki’, notes that while every play in Nepali theatre has someone responsible for sound design, many are more like “sound collectors” than true designers. “Dev dai is the only person who has truly dedicated himself to this craft,” Shrestha says.

“He knows how to elevate the text through sound,” Shrestha adds. “He evaluates the scene’s emotional value and finds ways to enhance it. He also collaborates with the actors, tailoring the sound to their movements and coordinating with the lighting design, ensuring all elements complement each other.”

Neupane’s journey into sound design began in the early 2000s when he started producing and directing radio dramas. After working professionally in radio between 2004 and 2006, he sought to understand the intricacies of acting and enrolled in the three-month acting course with the veteran director and actor Anup Baral. “While in that class, I would think about how I could express the scenes through sound,” he recalls. Although he was cast in the student production of ‘Banki Ujyalo’ once the course was over, he decided to work backstage instead. Director Baral suggested he focus on sound design.

Recalling that time, Baral says, “He came to my class already proficient in storytelling through sound alone. That is why I asked him to take charge of sound design in ‘Banki Ujyalo’.”

That was when he realised that a new path had opened up for him in a field he was really interested in, Neupane says. “From then on, I knew it was my domain,” he says. He hasn’t looked back since.

“One thing that makes him stand out is that he listens,” Baral says, “not just to the director and actors but also to the unspoken rhythm of the script… Over the years, I have seen him pushing the limits of sound and what it can do to a play—I have seen him use everyday sounds like that of rain and typewriter to add depth to the verisimilitude, and I have also seen him use unusual instruments to create a surreal atmosphere. In all of the plays we have worked on, he has made us internalise one important truth: that sound is used not just to hear but to feel, experience and remember. Neupane is a rare talent, and it’s been my pleasure to observe his adventures in sound from a close distance.”

Today, alongside plays, Neupane also designs sound for reality TV shows, having offered his craftsmanship for over ten shows so far. He will also soon work as the location sound designer for an upcoming film project.

Moreover, he also wants to pass down what he has learned to the upcoming generation. He has already developed a sound design syllabus that he plans to teach as a 15-day course for aspiring students.

Nepali theatre has seen remarkable growth over the past decade. There are now a handful of theatre groups active in Kathmandu and new theatre venues are opening up outside the Valley as well. Baral himself is constructing one in Pokhara.

Despite financial challenges, it’s important that all aspects of theatre—sound included—are taught independently and professionally. Neupane’s upcoming teaching project will certainly be a significant contribution to that effort—yet another step he will take to ensure that the “stepchild” of theatre gets a seat at the family table.

8.65°C Kathmandu

8.65°C Kathmandu