Theater

Deliciously dark, superbly surreal

Nisabdha Shumsher Rana is working on his final novel—a psychological thriller starring a serial killer who will conduct the prime minister’s murder on his 53rd birthday.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Nisabdha Shumsher Rana is working on his final novel—a psychological thriller starring a serial killer who will conduct the prime minister’s murder on his 53rd birthday. His scribe, an enigmatic young woman named Anindra, asks if it might not sound better to say “pradhan mantri ko hatya” instead of “prime minister’s murder” in English, as the novel itself will be in Nepali. Nisabdha disagrees. Even if the novel might be in Nepali, the English phrasing sounds better, he says. Anindra relents.

In the new play Bathtub, this interplay between the English and Nepali languages happen often, speaking to a critique that has often been leveled at novelist Kumar Nagarkoti, who wrote this play. Nagarkoti’s liberal use of English words in his Nepali language novels, short stories and plays has often been criticised by language purists. Bathtub is not Nagarkoti’s response to them; in fact, it is almost as if he is pushing them further, daring them to censure him more. After all, Nagarkoti has never been afraid of a little controversy.

Bathtub is quintessential Kumar Nagarkoti. Nisabdha Shumsher Rana is a writer who receives a phone call from death’s personal secretary, who tells him that his time is almost up but she’ll extend his lifespan just so he can finish his last book. His scribe Anindra once fell in love with a poet who wanted to bind his manuscript with her hair, so she cut it all off and gave it to him. As Nisabdha dictates his novel to Anindra, the primary character, the serial killer, comes to life, demanding a change in his fate. What follows is an at-times hilarious, at-times emotional existential struggle between creator and created, fate and free will, theft and inspiration.

Deftly directed by Ghimire Yubaraj, the play treads familiar Nagarkoti grounds, where the bizarre and surreal recur with alarming regularity. No one seems to bat an eye that the fictional serial killer has come to life and is threatening his creator with a gun. Anindra frequently transitions between dream and reality while Nisabdha receives a phone call from death’s personal secretary as if it were just another banality. The play progresses in episodes, punctuated by references to prose, poetry and Laxmi Prasad Devkota. In the post-modern world of Bathtub, one character breaks into song, another recites poetry and yet another quotes literature.

At the heart of the play is Nagarkoti’s fascination with language and how all languages play off of each other. When the serial killer meets Anindra for the first time, he remarks on her unique name, only he pronounces it as ‘yonik’, as in relating to the yoni, the Nepali word for the womb or vagina. One phrase, too, keeps recurring—black coffee khane ko mann pani black huncha (black are the hearts of those who drink black coffee). When Nisabdha attempts to substitute the Nepali word ‘kalo’ for black, the serial killer interjects, saying that’s not what he said—he used the word black, not kalo. This attraction to the nuances of language is evident in the names of the characters themselves, Nisabdha, meaning wordless, and Anindra, meaning sleepless.

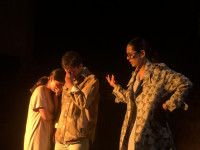

The play itself is a delight to watch, artfully transitioning from comedy to tragedy. The three actors are excellent. Bhushita Vasistha as Anindra is quixotic and starry-eyed, a perfect vehicle for the character. Brazesh as the serial killer is both brazen and wistful in his attempt to change the arc of his character. But the star of the show is Neer Shah as Nisabdha Shumsher Rana. The veteran actor-director is brilliant with his comedic timing and his eventual turn towards the tragic. All three actors play their roles with aplomb, amid a set that is creatively Spartan with the barest of minimums. Particularly clever is Anindra cascading a handful of letter tiles from her hands as an analogue for typing.

The hour and fifteen minutes of Bathtub go by in a flash of the serial killer’s crimson cape. The play moves swiftly, as Anindra and Nisabdha bicker over fictional nuances and the serial killer demands that they celebrate his birthday. Bathtub is playful and never takes itself quite too seriously. Even though the final act of the play gets a little too serious a little too fast, it is a believable turn. The audience goes from uproarious laughter to stunned silence in a matter of minutes but it’s a fair gambit. Unlike a lot of contemporary plays, Bathtub, like most of Nagarkoti’s work, is no social realistic drama. In fact, it seems to willfully disavow the entire genre, taking pains to break from the mould and do something truly unique in Nepali theatre.

Bathtub is playing every day except for Tuesdays at 4.30pm, and Saturdays at 1.00 pm, at Shilpee Theatre, Battisputali, until February 11.

12.62°C Kathmandu

12.62°C Kathmandu