Culture & Lifestyle

Stitching stories

Sofiya Maharjan, a young artist from Patan, reclaims the art of sewing to tell deeply personal stories of loss and acceptance.

Urza Acharya

Sofiya Maharjan grew up in the gullies of Patan. That was her world. Her parents and relatives were always close by, and school, leisure, and playtime were the crooked alleys and courtyards of clustered Newa houses. Perhaps that’s why, even as she grew older and ventured outside of her comfortable and enticing bubble, Patan has never really left her. Neither has she.

The magnificent city—some parts still stuck in antiquity—manifests itself in Maharjan’s art—embroidered in between creamy pieces of fabric; sometimes as a wooden door made some hundred years ago, and other times as a cup of tea that’s served to each visitor—without prejudice—morning to evening.

Was it ever too much? I ask. The overwhelming essence of the city and the proximity of everything must have been overwhelming at times. “Well, the festivals were a bit boring. And I never got to travel because everything was within walking distance,” she says. “Also, dating was a nightmare.” We both chuckle.

Around 2015, Maharjan reveals she became disenchanted with Patan. “I signed up for an art school in Bijeshwari, Dallu.” That was possibly the first time her bus rides became longer. But it was still a fond experience, as she made new friends.

Like many urban students deciding the whats, hows and whys after high school, Maharjan too was torn about what direction her life would take as she turned 16. She enrolled in science. She also quickly realised it wasn’t for her. Till then, art was never in the picture—a dream that one didn’t dare tread into. During her break, though, there was a calling. “I joined Bara Fine Art Institute in Lagankhel, Lalitpur,” she recalls. “I could barely draw. But I picked it up pretty quickly.”

Those 15 days of art classes made her realise more about herself than years and years of schooling. She joined Plus Two again—but this time in arts. That’s what brought her to those long bus rides to Dallu. Moving away from anything remotely comfortable, from distance to familiarity, Maharjan started a new chapter of her life.

Her fervour for art soon brought her to the doorstep of Kathmandu University’s fine art department. This was in 2017. During the Covid lockdowns, Maharjan was tasked to archive her family’s history as a part of her assignment. Be it via photographs, paintings or other mediums, the purpose of the assignment was to create art within one’s house and find meaning in mundane objects. “As my peers were busy documenting their family photos, I had nothing.”

Maharjan had a complex childhood. Her parents split when she was a child, her mother left home with Maharjan and her brother and started a new life. “When we left, we left emptyhanded,” she says. So Maharjan didn’t have anything to archive, everything was new—the photographs, the furniture, the utensils, and the memories. When she asked her father’s family to lend her some photos of her childhood, they were unresponsive. “I’d never felt so out of place,” she says.

But her mother and her side of the family comforted Maharjan. Her mamaghar became her muse. Her grandmother, her ‘maa’, had only just passed away. So Maharjan found it apt to pay homage to all the memories of her maa. This is how her series ‘Mamaghar’ was born.

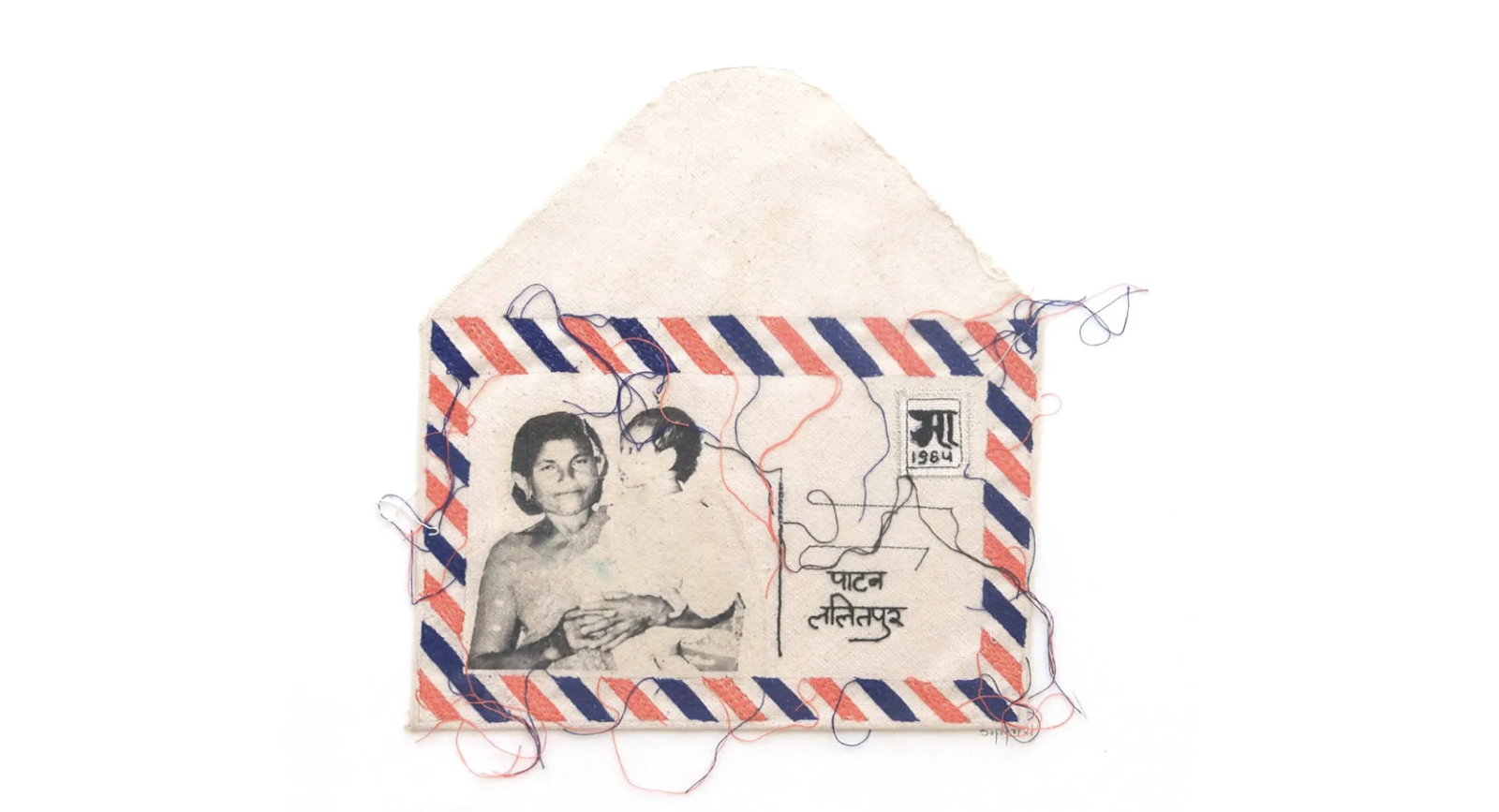

The series follows a series of letters stitched in off-white fabrics—the classic combination of blue and red bordering the envelope’s rectangle. In between them are bits and pieces of memories attached—transferred photographs of Maharjan with her Maa, the family sanduk, or a bag hung at the door.

But ‘Mamaghar’ is, in a way, a cruel word. It inherently implies that a mother’s house—the very house she grew up in—was never really hers. That her childhood, her memories were temporary passengers. Because in the end, that house, that home, was and always will be her brother’s.

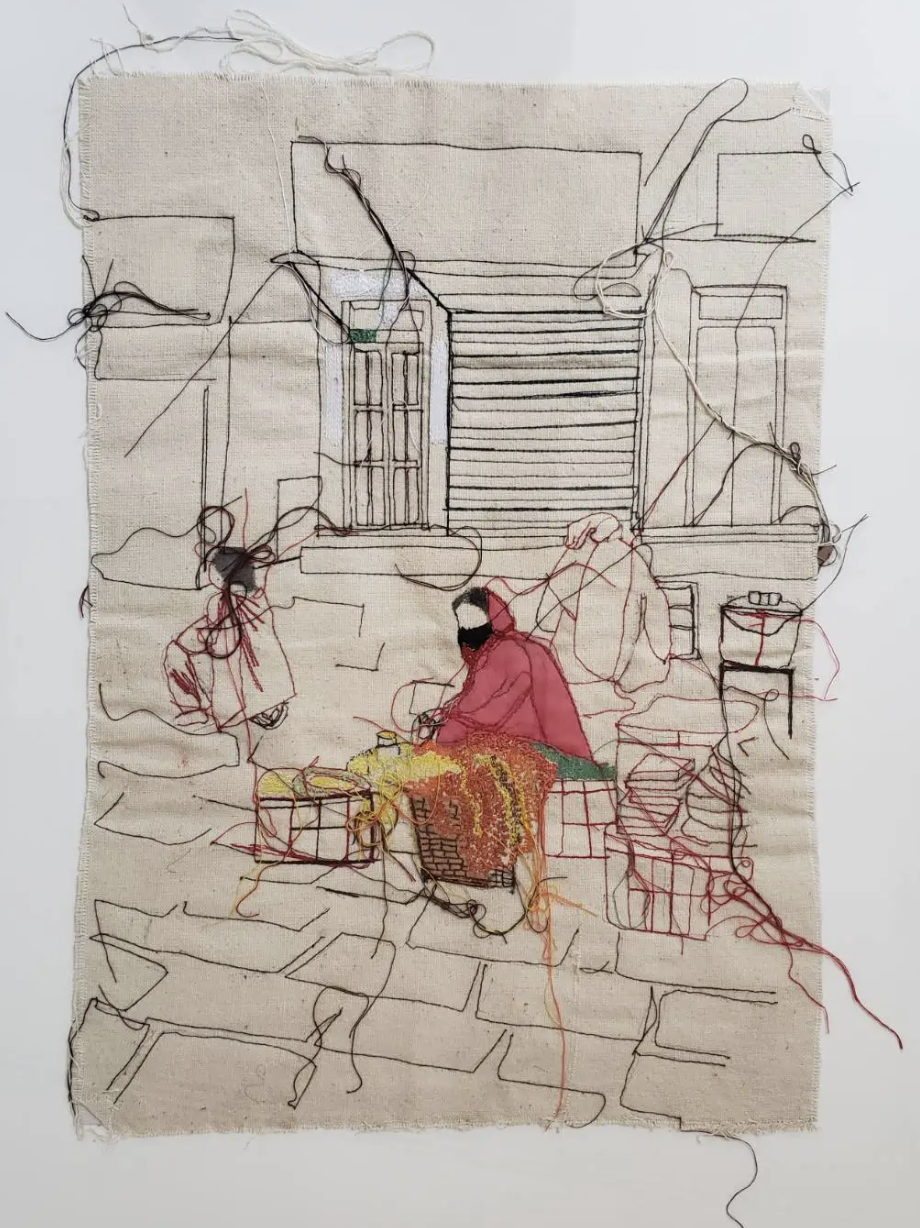

After ‘Mamaghar’ came the series ‘A Small Walk.’ More external but equally poignant, this collection features stitches of the classic valley cityscape, the compact wooden windows, and beside them, the narrow alleys where street vendors sell tea, chatpate, peanuts and the like. As the title hints, the artworks are replicas of the Patan Maharjan sees as she trods the gullies.

One particular work, ‘Market II’, features a woman selling garlands of fresh flowers in a doko—mainly marigolds. Her red silhouette, sewed in rather meticulously—shows her waiting patiently for customers to come and lighten her load for the day. Around her is the chaos of the urban life, buildings, steps, pavements and threads flow on about. Yet, there is a sense of calm in her posture.

Maharjan’s most recent exhibition was ‘Absence Unbothered’ at the Dalai-la Art Space in early May. Along with her continued introspection with everyday objects, it also featured tracings and stitches of her childhood—her mother, her brother and herself. Though their faces remained untraced, the details manifested themselves in the clothes or the jewellery.

It shows completeness within the absence. The ‘unbothered’ so aptly put after ‘absence’ hints towards the notion that sometimes it’s perfectly alright and perhaps even necessary to steer away from familiar or ‘idealised’ situations—be it family, friends, or location—if they bring you pain or chaos. It subverts the idea of an ideal family—one that’s only complete with a masculine presence—to show that there is love and strength in what others deem insufficient.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)