Culture & Lifestyle

For queer people with disabilities, the path to acceptance is more arduous

They face more prejudices in the forms of queerphobia and ableism, activists say.

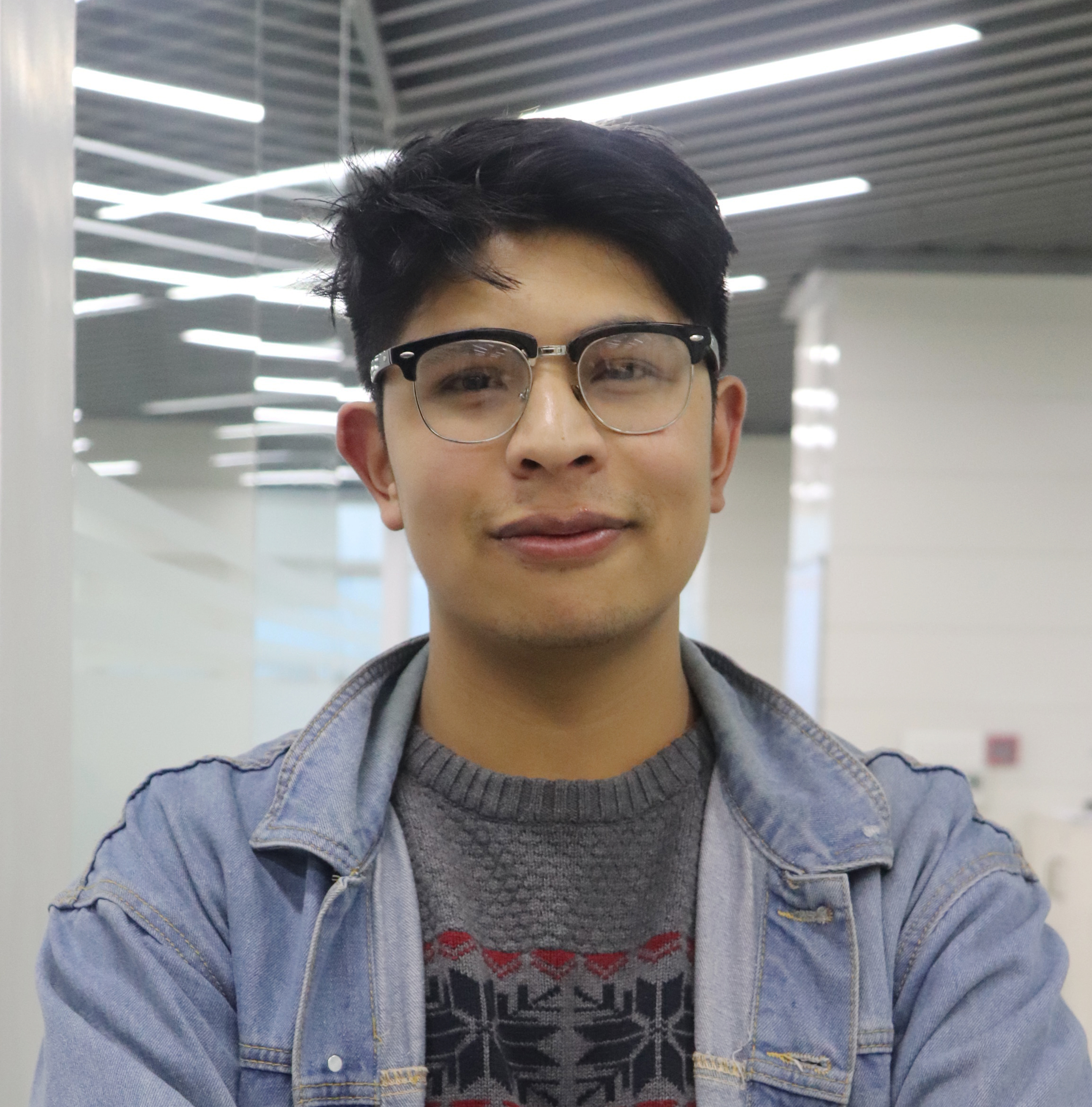

Ankit Khadgi

On the morning of March 12, 2020, Deepak Paudel, a daily wage labourer who moonlights as a dancer, was returning home in Parsa Bazar, Chitwan, after performing at a wedding in Narayanghat.

While crossing the road near his home, Paudel, a bisexual, was hit by a speeding tipper and he lost both his legs. The accident completely changed the trajectory of Paudel’s life.

His disability has meant that he can no longer work as a labourer or a dancer and has been facing difficulties providing for himself. What has made matters worse is the increased discrimination that he now has to face.

“I have always faced discrimination from family, friends and other people for being a bisexual. But when I lost both my legs, the discrimination amplified. Before, I could provide for myself. But now I am unemployed and face more prejudices than ever for being a queer as well as a person with a disability,” says Paudel, 39.

In the past two decades, Nepal’s queer movement has made several progressive changes in the country’s policies and laws. From legalising homosexuality in 2007, guaranteeing rights for a certain section of the queer population to ensuring protection for the queer community in the country's constitution, the queer movement in Nepal has helped amplify the voices of the queer population.

However, according to queer disability rights activists, who spoke to the Post, Nepal’s queer movement has failed to address the concerns and issues of queer people with disabilities.

“Our issues and voices have never been acknowledged,” says Safal Lama, a non-binary queer disability rights activist. “We have largely remained invisible from conversations related to queer issues. We do not get enough space to voice our concerns as able-bodied queer people. There has been a little effort to include us in the queer movement in Nepal.”

According to Lama, the lack of inclusive queer spaces for people with disabilities is an issue that has never been questioned or challenged within the queer community of Nepal.

“We have seen many changes because of the queer movement but when it comes to us [queer people with disabilities], our rights and needs have always been ignored. Even if we speak about it, the queer community doesn’t listen to us, and they say that disability is a different issue and should not come under queer agenda,” says Lama. “But it’s not. For the queer movement to uplift everyone, issues of queer people with disabilities should be given equal focus.”

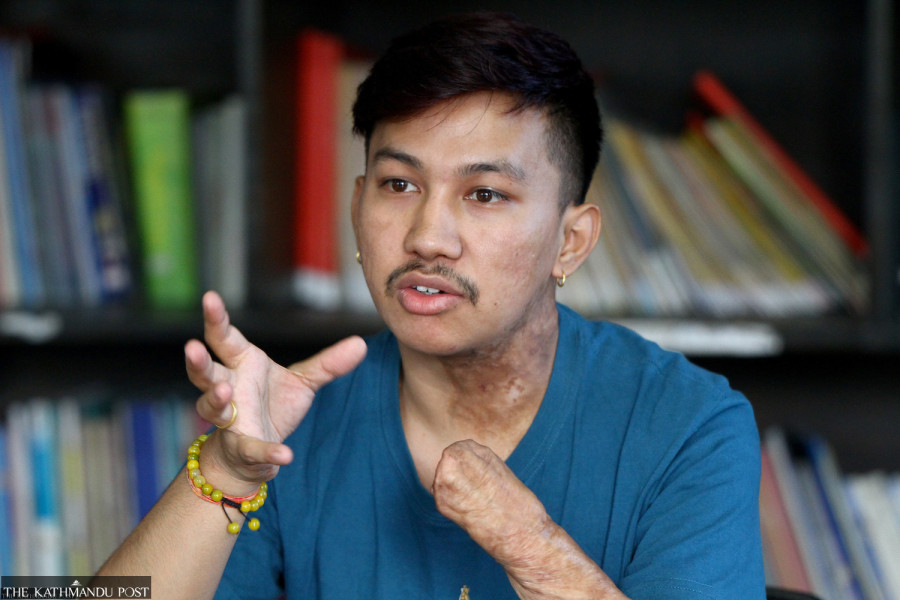

Aditya Rai, a queer disabled activist who works at Blue Diamond Society (BDS), an organisation that advocates for LGBTIQA+ rights, agrees with Lama. Rai, who joined BDS in 2011, says that it’s not that the conversation of guaranteeing the same rights and opportunities for queer people with disabilities hasn’t spurred.

“I started out as an activist in 2011 and since then I have made efforts to make other queer activists realise why it is important to include voices of queer people with disabilities. But there’s always lack of concern from them as they believe that disability organisations, not queer organisations, should handle our issues,” says Rai. “In Nepal, queer people with disabilities are marginalised within the marginalised community of queer population.”

The problem of lack of inclusivity, however, is not limited to Nepal. Lack of inclusive queer spaces and the ableist attitude within the queer community are common across the world.

“Our society’s way of looking at disabled people itself is problematic,” says Payal Thapa, 22, a trans activist from Nawalparasi, who lost her right leg when she was a child. “But when a person with a disability is queer, then society holds even more prejudices against them. I had to suffer from discrimination in my personal and workspace from both cisgender heterosexual people and my queer friends for being disabled. They still call me with various names and always say that I am good for nothing.”

In a society that is yet to fully accept queer people, it has become crucial for queers to build an all-inclusive community of their own.

However, queer people with disabilities the Post spoke to say that one of the major struggles they face is getting acceptance from their own peers.

“I feel left out and excluded as the queer community hasn’t accepted that people with disabilities can also be queer,” says Rai, who’s currently working as a programme officer at BDS. “They have this mindset that, to be queer you have to be able-bodied. Once you are disabled, even if you say that you identify as a queer, they question you and your choice.”

But’s it not just the queer movement that has failed to accommodate and give space to the voices of queer people with disabilities. Even disability organisations, say queer people with disabilities, have failed them because of their heteronormative beliefs.

“Once, when I attended an event organised by and for people with disabilities, I had raised the issue of how disability rights movement leaves behind queer people with disabilities. Most of the attendees and organisers didn’t validate my concern. They started asking me if I could provide them with the number of queer people in the country’s disabled population, exerting a belief that we [queer people with a disability] barely exist,” says Lama.

In the various policies and acts that have been made for people with disabilities, the word queer or LGBTIQA+ hasn’t been mentioned at all. Neither has there been any focus drawn to address the needs of queer people with disabilities by any particular institution.

The lack of acceptance from the queer community has meant that for queer people with disabilities who want to explore their queerness, there's no place to learn about queer issues, which creates difficulties for them in accepting their identities.

"People like us aren’t welcomed with open arms in queer institutions. And when we go to disability rights organisations, we are told that a disabled person can't be queer. Because of such unwelcoming spaces, it's challenging for a disabled person to accept both of their identities," says Rai.

Activists from both the disability and queer rights movements accept their failure to include queer people with disabilities.

“We agree that we have been unable to address the voices of queer people with disabilities. Most of our focus has been on demanding rights for the whole community. But it is true that even within our community, they are the ones who have to face more prejudices. We will try to work together with them in the future,” says Mitra Lal Sharma, president of the National Federation of Disabled Nepal.

Manisha Dhakal, executive director of BDS, also agrees with Sharma. According to her, there’s a huge knowledge gap within queer organisations about issues related to queer people with disabilities, and this has made the country’s queer movement less inclusive.

“We haven’t been able to use an intersectional approach in queer activism as queer activists lack information about queer people with disabilities. But it's high time we change it and work towards addressing the needs and demands of queer people with disabilities,” says Dhakal.

Not accepted by queer and disability organisations, queer people with disabilities are now working independently and forming communities to advocate for their rights.

In May this year, Lama started Queer Disabilities Nepal, an Instagram account, to build a community where queer people with disabilities can connect with one other.

“I had started a Facebook page targeted for queer people with disabilities, but I failed to use the page actively. But in May, I decided to start using Instagram. I know it’s just an Instagram account, but I wanted to start a conversation and build a community among queer people with disabilities, many of whom have not received any space till now,” says Lama, who’s also a psychosocial counsellor and one of the members of Queer Youth Group, a youth-led queer organisation.

Lama says that through the Instagram account, they have been able to form a group of 15 queer people with disabilities from different parts of Nepal.

“I came across the Instagram account last July. I've always known that there are people out there who are like me. Not just physically but emotionally and in their sexual preferences. Connecting with others like me through the Instagram account has made me feel less alone and inspired in many ways,” says A, a 22-year-old bisexual woman and one of the members of the group, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Since the conversation on queer people with disabilities has just started in the country, activists believe that there’s a lot yet to be done in Nepal’s queer disability rights movement.

“Queer people with disabilities are already in a very physically and emotionally vulnerable place,” says A in an email interview. “An inclusive space in all social movements is important as it creates a safe have

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu