Culture & Lifestyle

The inclusivity problem with Nepal’s census

The Central Bureau of Statistics’ upcoming census decision to count all the queer population under the category of ‘others’ is highly problematic, say activists.

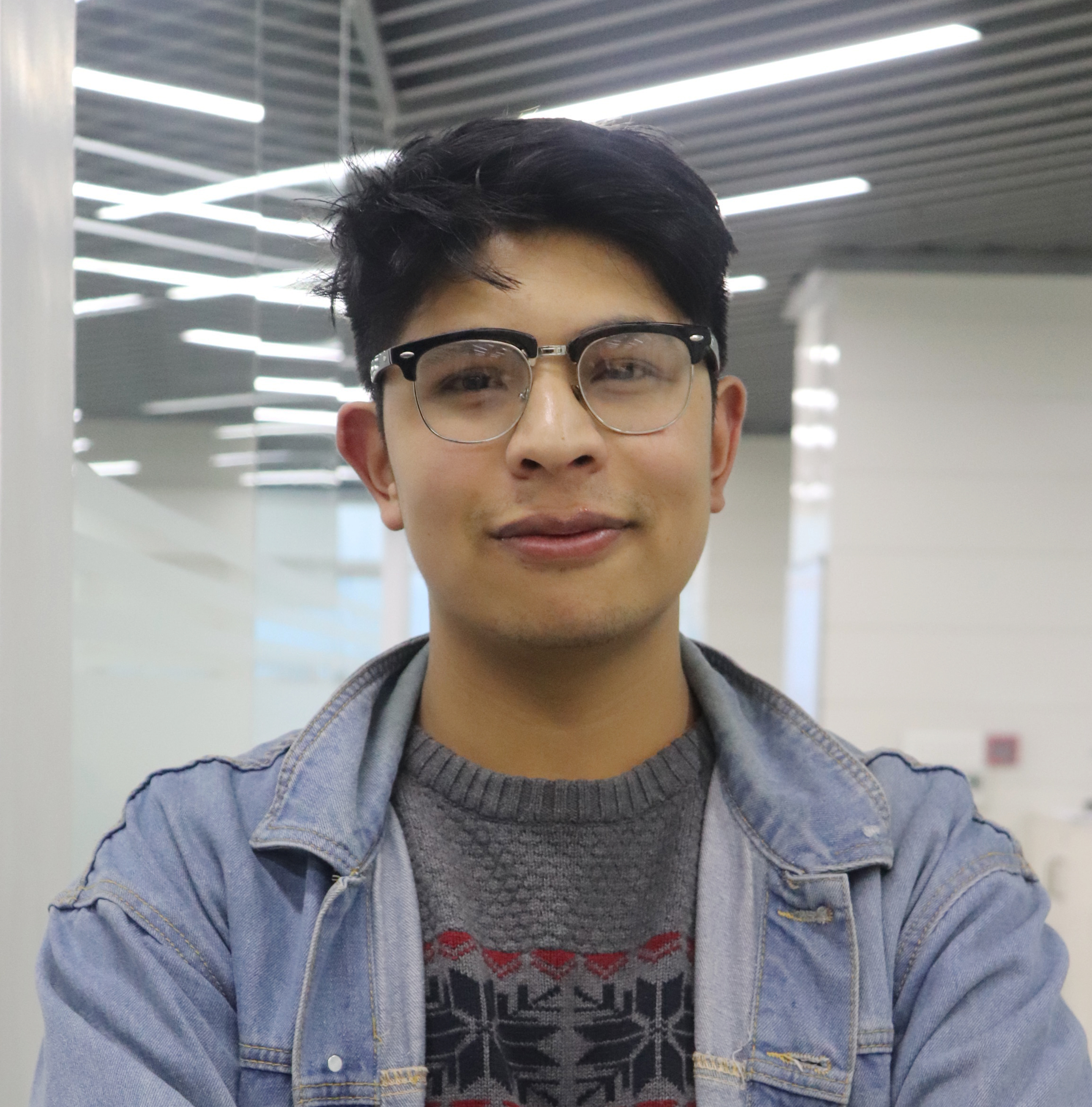

Ankit Khadgi

Last year, just a month before the nationwide lockdown, Nepal made news in the international media.

Nepal was preparing for its national census, which takes place every ten years and the country received praise from the international media and communities for making the census inclusive. Central Bureau of Statistics informed that it will add an option of ‘others’ beyond the two genders (male and female) to count the queer population.

But even though the country was being celebrated, for many of Nepal’s queer population, this news wasn’t a progressive one.

The adding of ‘others’ as a gender option, say activist, makes it compulsory for the queer population to select the ‘others’ category even if they didn’t identify with the gender marker.

This forceful decision to count them under ‘others’ category is discriminatory, they say, since it takes away their right to self-determine their gender identity and sexual orientation.

“This decision of CBS is reflective of the widespread misconception and lack of awareness of gender identities among policymakers,” says Rukshana Kapali, a trans rights activist.

Since Nepal does not conduct any periodic surveys on a large scale, it’s the decennial census data, the accuracy of which has always been contested, that the government and non-government organisations rely on to distribute economic, social and political resources.

In 2011, the Nepal government did make an attempt to count ‘third gender’ people but their efforts were futile as only 1,500 people identified as the third gender, a number that didn’t reflect the ground reality. Similarly, since the census excluded queer people beyond third gender identities, it wasn’t able to paint the realities and collect accurate data.

And that’s why many queer activists say they had their hopes pinned on the 2021 census to make their presence felt and make the whole country realise the diversity within the queer spectrum.

“Data are not just numbers. They also mean recognition. If we are able to collect desegregated data of queer population acknowledging its diversity, it will benefit the whole queer movement and also its advocacy,” says Esan Regmi, an intersex activist.

Queer activists say they had actively advocated at the government level to include multiple options for sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics in the census so people could actually choose an identity they agree with.

But the CBS, they say, didn’t pay heed to any of their concerns.

According to Nebin Lal Shrestha, director general at CBS, including ‘others’ as a gender option is the only way through which the population of the queer community will be counted in the census.

“We have included the ‘others’ as a gender option to count the population of the queer community in the upcoming census. All those people who fall under the queer spectrum will be counted under the ‘others’ category,” says Shrestha.

But not every queer person identifies as ‘others’. There are queer people who identify as male, female, and non-binary. Every person’s sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics (SOGIESC) are different, and they can’t be categorised into one single category, which the institution is doing in the census.

“Using ‘Others’ as terminology to refer to gender identity is highly contested and even considered derogatory for many. There are people who identify within the non-binary spectrum, and people who identify as third genders. Not acknowledging different identities is failing to realise the different forms of oppression, marginalisation, exclusion, discrimination, violence and non-representation of those distinct social groups,” says Kapali.

But that’s not the only issue with the current census.

In August, last year CBS published two official questionnaires for the 2021 census.

“Only a single question in one of the questionnaires has mentioned three gender options—male, female, others. The rest of the questions have only male and female as gender options. To be honest, it feels that they have added ‘others’ as a gender option just to show they are being inclusive, but in reality, they aren’t,” adds Kapali.

However, Shrestha argues that CBS did make consultations with queer organisations, before adding the ‘others’ option in the census.

“We held multiple meetings with queer activists and it is only after consultation with them that we decided to add the ‘others’ option,” says Shrestha.

According to Bibek Sushling Magar, program officer at Federation of Sexual and Gender Minorities Nepal, the majority of people from the LGBTIQ+ community who attended the meetings were third genders.

“Within Nepal’s queer community, third-gender people are the majority. It is this majority that often shapes policies related to the country’s LGBTIQ+ community, which also happened with the CBS’s decision to include ‘others’ gender option,” says Magar.

But many efforts were made by activists to explain to CBS how the boxing of the queer community into a single category and mixing of sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics (SOGIESC), could actually affect the population and their movement.

“Our group was invited to the meetings with the CBS as well as other parties who were involved in the census. We tried hard to explain the necessity of collecting desegregated SOGIESC data and the fact that it won’t be justifiable to count the queer community within one category, as not everyone wants to identify as ‘others’. We also submitted various practices from the UK, New Zealand, Kenya and their documentation as well as reports to help CBS find ways to be inclusive to the whole queer community. But our voices weren’t entertained,” says Regmi.

But according to activists, it’s because of the country’s problematic laws that led the CBS to impose the ‘others’ gender option for the whole queer community.

Although Article 12 of the Constitution of Nepal enshrines the provision of getting citizenship as per the gender identity an individual prefers, in 2012, a directive was issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs, that went against this provision. As per the directive, which was based on the Supreme Court’s 2007 hearing of the Sunil Babu Pant & Others vs Government case, in Nepal LGBTIQ+ individuals will only be granted citizenship with ‘others’ as a gender marker.

And since CBS is also required to follow the legal categorisation, this could have led them to use ‘others’ as a gender marker in the census, as even though it’s problematic, it is legally accepted.

Although the 2007’s Supreme Court decision popularised the narrative that all queer people are ‘others’, many efforts have been made by young activists like Kapali, Regmi, and Magar to protest against the forceful imposition of ‘others’ as gender identity.

Kapali along with a few other activists have challenged the ‘other gender’ legislation by filing a complaint against the directive at the National Human Rights Commission and writ petitions at the Supreme Court.

The 2021 census, says activists, could have been a great time for CBS to reflect and rectify the mistakes the state has made by allowing people to identify with gender identities and sexual orientations of their choice.

“However, neither the civil society groups nor the government agencies paid heed to our concerns regarding this problematic categorisation of ‘others’,” says Kapali.

Regardless of all the efforts made by queer activists to aware CBS of the negative impacts the ‘other’ category can lead up to, according to Shrestha, it is almost finalised that the queer population of the country will be counted under the ‘other’ category in the census.

“We finalised everything only after consultations. Although we agree that we won’t be able to collect exact data because of the limitations, we have tried our best to be inclusive. When the counting will take place, we will also have supervisors from the queer community and we have also planned to do sample surveys with queer organisations to find comprehensive data later,” says Shrestha.

And with Nepal in the midst of a devastating second wave of COVID, all census-related works have been postponed and there’s no confirmation regarding when the census will take place.

However what is sure is that whenever the census takes place, it’s not going to be inclusive to all queer people. And according to activists, this will negatively impact them and the whole queer movement.

“This incorrect data collection process of the census will lead to a misrepresentation of data,” says Kapali. “ This will mean that the already marginalised, excluded and discriminated groups will be further removed from the national, regional and local level planning process and their concerns will not receive the needed attention.”

And that’s why activists believe that CBS needs to rectify their mistake and change the definition of ‘others’ gender, they say.

“Even if they won’t include the whole queer spectrum, they can only include those people under the ‘other’ category who identify beyond male or female. They cannot use the ‘other gender’ box to count what is not even gender and those queer who identify as male or female,” says Kapali.

“Sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics are three different things. Lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) are not even genders. Transgender men are men and trans women are women. And being intersex (I) is a sex characteristic and they can have any gender identity. It is a blunder to define LGBTI as ‘others gender’.

“If CBS fails to rectify such a definition, we will challenge this at the court,” she adds.

14.24°C Kathmandu

14.24°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)

.jpg&w=300&height=200)