Culture & Lifestyle

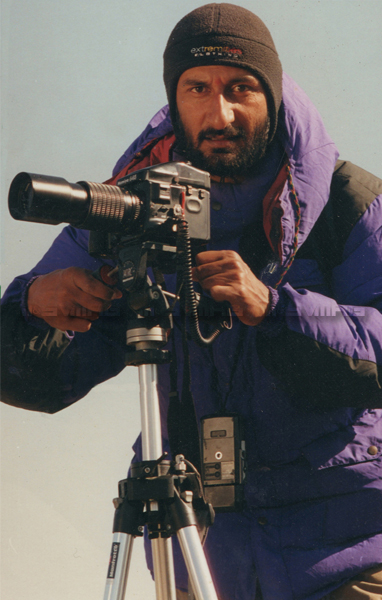

A man of the mountains: Tracing Jagadish Tiwari’s remarkable journey in landscape photography

Tiwari was 12 when he held a camera for the first time. But it was only after serving eight years in the Nepal Army that he realised landscape photography was his true calling.

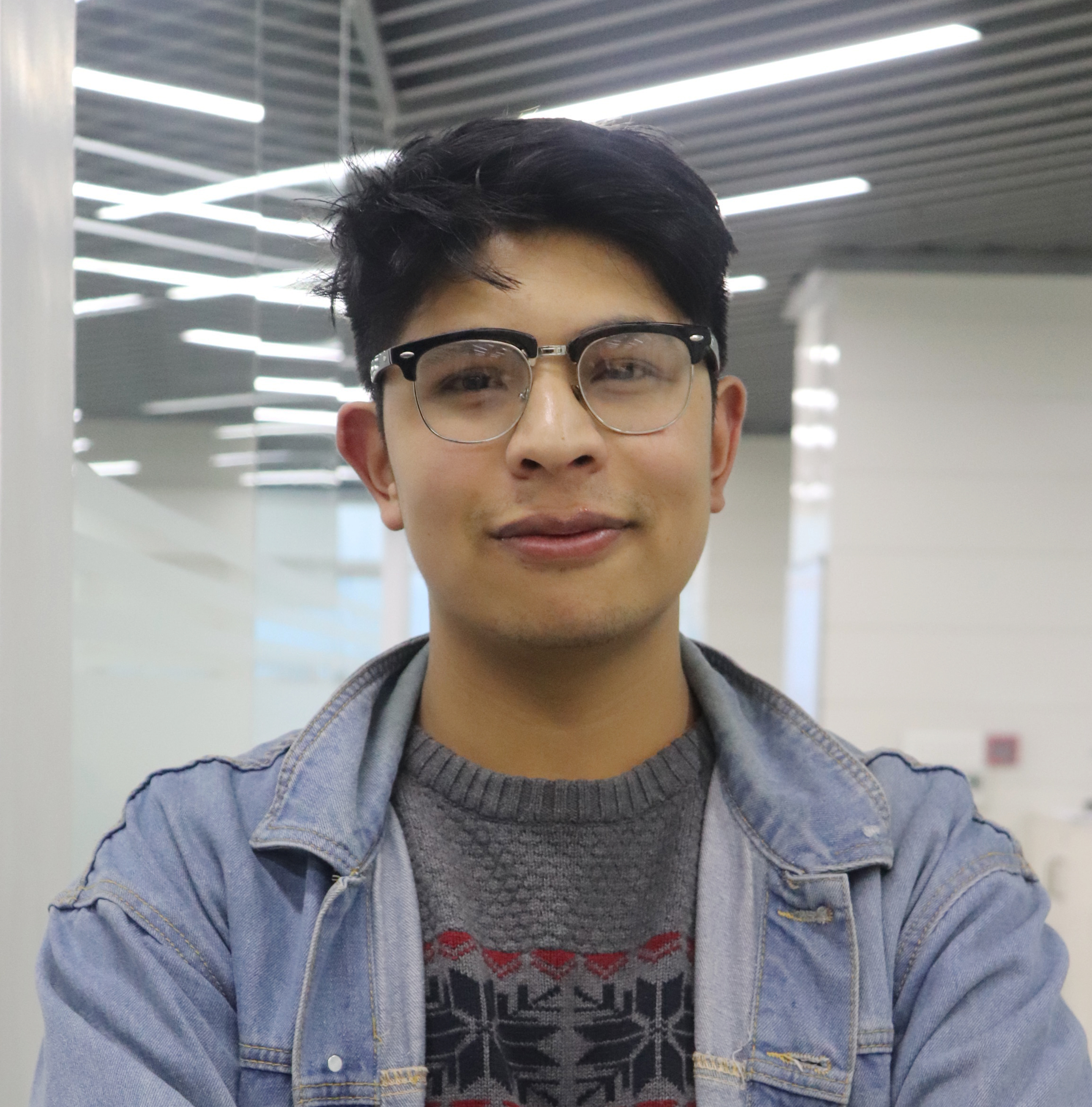

Ankit Khadgi

Jagadish Tiwari distinctly remembers the trip he made to Tilicho Lake, in Manang, back in 2009. He remembers it clearly because he thought he was going to die.

It was a particularly windy day, he says. He was inside his tent, struggling to stay warm, when a sudden gust of strong wind tore open his tent, sweeping it away.

“At that moment I thought I was going to die. Yet, all I could think about was my camera. Slowly when the wind was less strong, I opened my camera and took a photograph, as I had always imagined spending my life’s last moment like this--clicking a photo,” says Tiwari, who eventually survived the snowstorm.

Born in Tanahun to a family of farmers, Tiwari had never imagined he would one day become such a respected name in photography. In his more than three decades of career in landscape photography, Tiwari has created his own niche and his captivating photos are adorned on walls and on posters and photo books all over the world.

Tiwari says that he was 12 when he was introduced to the world of photography. “An American Peace Corps volunteer had come to stay with my family, in our home. Since I was the oldest among my siblings, he was closer to me. We would travel all over the village,” he says.

After six months of his stay at Tiwari’s home, the volunteer returned to his country. As a farewell gift, he left his camera.

“It was a Kodak 101 pocket camera. But it had no reel. Back then, buying reels were unaffordable and inaccessible for a middle-class person like me. So, I just took the camera and roamed around my village acting as if I were clicking photographs for real,” says Tiwari.

After finishing his School Level Education, Tiwari left his village for Kathmandu. All he knew about the city was what his friends and family told him. But when he saw the city with his own eyes, he was mesmerised by the chaos bubbling through the town, he says. “For someone who lived in a village, surrounded by quietness and nature, living in Kathmandu was very, very different. I was even scared to walk around. Whenever I saw a bus, I thought that it was coming towards me,” says Tiwari.

Tiwari, who was 16 back then, knew no one except a friend who lived in Bhaktapur. The two would walk around Kathmandu all day, he says. On one such day of walking, they decided to take some rest in Tundikhel, enjoying the warmth of the sun on a cold day. Then destiny came into play.

Near where the two were sitting, a group of the army men were practising. “My curious eyes got their attention. I couldn’t control myself, so I went over and talked with them,” says Tiwari.

The conversation wasn’t limited to small talk. Tiwari’s ability to articulate and his attractive personality left an army officer so impressed that he was instantly offered to join the army.

“I was confused that I didn’t know whether to join the army or not. But my friend suggested that I join. I followed his advice,” says Tiwari.

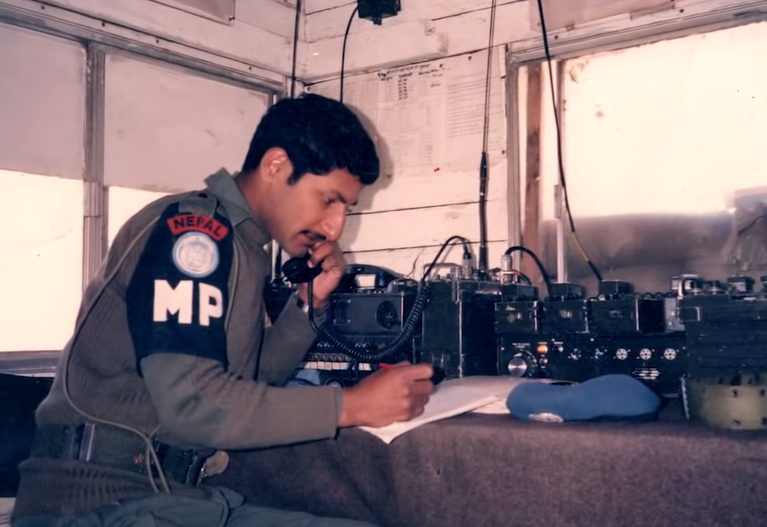

For a young, naive teenager who had no exposure to the outer world, joining the army and living a life of discipline was challenging. But his sincerity and dedication impressed everyone in his battalion, he says. And they were all familiar with his interest in photography.

“One day, my commanding officer called me to his office. He also had a passion for photography and owned expensive cameras and lenses, which back then only a few Nepalis could,” says Tiwari. “He asked me if I could click photographs with his camera. I was scared. Besides using the pocket camera, I had never had a chance to operate other cameras.”

Saying ‘no’ to someone of authority in the army is forbidden, he says, thus he immediately replied in the affirmative. The commanding officer then made him the photographer of their battalion.

Having signed up for a job with no real experience, Tiwari then started learning photography in any way he could. “I roamed around the city, following tourists who had cameras. I used to closely see how they clicked photos and the lens they used. Similarly, I also used to visit photo studios to see and try to learn from people who came to develop their films and visited bookstores to read the books about photography,” says Tiwari.

Slowly, he started gaining confidence in clicking photos. And he started developing a strong penchant for photography, says Tiwari. His work improved greatly over the years, and he was also later promoted and started working in the photographer department of Nepal Army. But after working for eight years, he decided to quit. He felt that he just wasn’t connecting with the photos he was taking.

“I was mostly capturing the training sessions of army personnel and fighting they were involved in. But nature, which always made me happy, was what I wanted to capture. It had always been an intrinsic part of my life and I had this urge to capture its beauty, which was not possible if I continued working in the army,” says Tiwari, who left his stable job at the Nepal Army to pursue his passion for landscape photography.

This change in career wasn’t easy, he says, particularly in the early days. He was married by then and had to take care of his two children as well as his family members. But he felt he had no choice but to pursue what he felt was his calling, as for him it was in nature where he was at his best.

“Since my childhood, I enjoyed the solitude nature provided. Whenever I am alone with nature, I feel I can communicate my emotions. I feel it can understand me,” says Tiwari.

That’s why after quitting his job at Nepal Army, Tiwari embarked on a mission to capture the treasures of nature, and for it, he was ready to do anything, he says. “You can say I was madly in love with my passion to capture the beautiful landscape through my camera. I don’t know whether photography loved me back or not, but I loved it and still love it without any expectations,” says Tiwari.

Making the snow-capped mountains, the luscious green hills and the serene lakes and ponds of Nepal his subject, Tiwari travelled all over the country. While he was unsure about the possibility of having a stable future in landscape photography, his photos were getting appreciated for their technical composition and aesthetic beauty.

“I feel very lucky and blessed as things went as I had hoped. People showed interest in my work and I could sustain myself working as a landscape photographer,” says Tiwari, whose photos are now almost ubiquitous for landscape photography.

For him, his pictures are not just the reproduction of an image through the celluloid. Every photo has a story of joy and struggle, he says, and that makes it difficult for him to sell his work.

“For my survival, I don’t have any option other than selling these photos. I have to sell it and put a monetary value on it, even if it breaks my heart to do so,” says Tiwari.

For his pictures, he travels far and wide. And for that, he sometimes has to walk endlessly for days to reach his destination. There are days when he doesn’t see any people and eats whatever is available. And days where he has to walk in below freezing temperature.

But nothing deters him from capturing the picture he wants, as he doesn’t fear from anything, he says. “When your mind is free from fear, you can achieve anything. I don’t fear dying. I don’t fear losing anything,” says Tiwari. “ All I do is sincerely follow my passion and work hard in capturing the photo I want. For this, I am ready to walk a thousand miles, stay hungry for hours, visit the same place again or even risk my life.”

When one listens to Tiwari talk about photography, they see a man content with his work and life. In the last three decades, he has been to Kalapathar more than 35 times to capture the majestic Mt Everest. Likewise, he regularly travels near the high summits, the rolling hills and pristine lakes. However for a photographer of this magnitude, he still says he hasn’t clicked the photo he can love the most, he says.

“There’s no definition of success in my art. I believe that if I succeed in photography my path ends, which I don’t want to,” says Tiwari. “I want to keep on clicking as much as photos I want to, even a few seconds before my last breath in this world as there’s nothing in the world that can make me happy except clicking photos of nature.”

19.71°C Kathmandu

19.71°C Kathmandu