Culture & Lifestyle

A disconcerting time for Nepal's only music museum

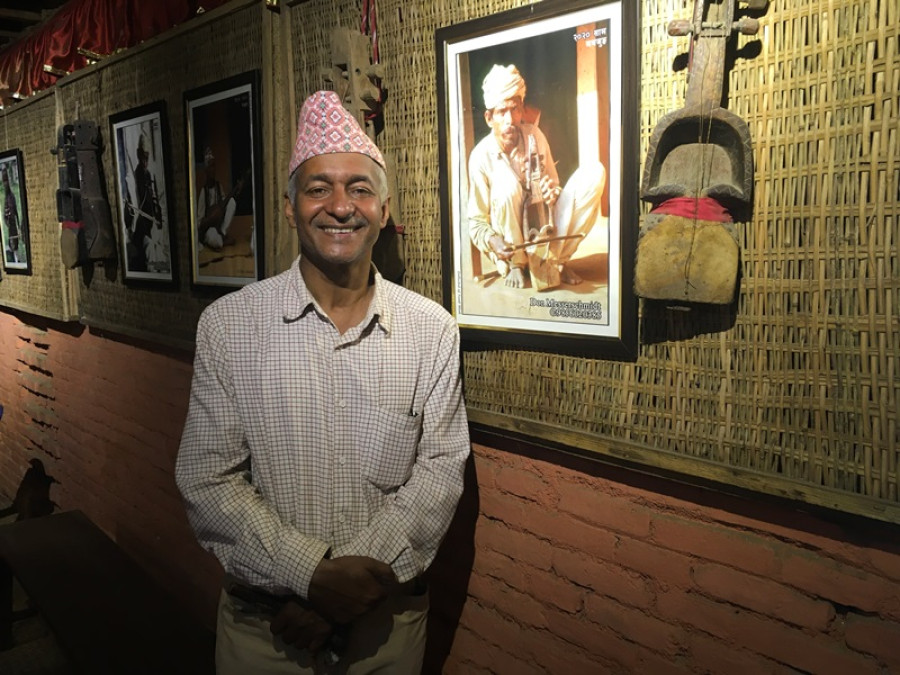

After 25 years of bringing diverse folk musical instruments together, the Nepali Folk Musical Instrument Museum is looking towards an uncertain future.

Srizu Bajracharya

Folk musical instruments are an integral part and experience of diverse Nepali cultures and traditions. When Ram Prasad Kadel envisioned a folk music museum, he believed the stories surrounding folk instruments would educate people about diverse communities and their practices. And his museum would be instrumental in preserving such stories for future generations. And for the past 25 years, his museum, Nepali Folk Musical Instrument Museum, undertook that task independently. But today, the museum is struggling to save its purpose.

On a recent afternoon, when Kadel turned on the lights of the museum, the only music museum in the country, he realised that soon he would no longer be able to do that. An array of Nepali folk instruments are placed inside the museum, but they are filmed in dust. There's water trickling down the roof, and you can smell the petrichor of the old structure. The museum feels uncannily quiet—and deserted.

For the last two years, Kadel had been fighting a court case to increase the lease on the eastern building at the Tripureshwor Mahadev bahal, where the museum is situated. He had been fighting the case against Kathmandu University, to whom Guthi Sansthan, the committee who owns the space, has promised the land. He lost the case in the latter part of 2019, and since has been uncertain about the future of the museum, of where he will relocate or take the museum's valuables.

"I have come to accept reality. I have lost the case that I was fighting against the Guthi Sansthan and Kathmandu University. There's nothing more I can do for this place, and sometimes I think I should just take everything out in the open and let it soak, out in the rain, so everyone can see what it has come to for this museum," says Kadel.

"The case was ruled out with the judgement that I didn't have enough claim for the building," he says. But there’s more to it, says Kadel. He had been asked to leave the space in 2017 for the renovation of the building by the Guthi Sansthan. But later he found out that the building was already being leased to Kathmandu University’s music department, even before his five-year renewable rent contract with the Guthi Sansthan, which was to end in 2019, had expired. After coming to know of this, he refused to move and took the case to court.

"There's a lot of politics involved. And I know I have to relocate," he says. "All I wanted was to save this endeavour of documenting our lok baja [folk musical instruments] through this space. These instruments are a heritage on their own. And if we forget them, we lose more than just music; we lose our culture and history," he says.

Kadel, who is a thangka trader by profession, started collecting folk musical instruments in 1995. Later in 1997, he opened Nepali Folk Musical Instrument Museum registering it as a charity organisation using a small space in Bhadrakali. The museum was supposed to be a gift to his teacher Guru Swami Akhandananda Saraswati who had taught him meditation. And in 2007, under the referral of the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Aviation, who had recognised the museum’s work, Kadel had relocated to Tripureshwor.

Kadel, with other members of the museum, slowly started to expand their collection, travelling across the country, not just to accumulate bajas but also to learn and conduct research with indigenous communities.

The research has become an integral part of the museum's work, and it has also organised numerous musical festivals. In 2011, it also started a folk music movie festival which used to be hosted every November in Naach Ghar before the earthquake. While the museum remains relatively unknown, occasionally groups of students frequented the museum as part of their educational tour. And before the pandemic, about 200 to 300 visitors used to visit the museum every day, says Kadel.

"The museum has benefited a lot from being in this area; we had more growth opportunities here as the space allowed us to have more interactive programmes," says Kadel. "Location wise, it's near other museums, and so schools taking children to visit museums make time to visit this museum, as it's just on their way and near local transport facilities," he adds.

The museum has also been publishing articles related to endangered folk music instruments in their biennial journal 'Baja'. It also hosts regular live sessions featuring unique instruments of various regions of Nepal and gives music training. And through Kadel's initiation, a chapter about folk music instruments was also included in the social studies curriculum for grade 10 students.

"The music museum has done significant work in terms of how it has documented the musical diversity of the country,” says Swosti Rajbhandari Kayastha, lecturer of museology at Lumbini Buddhist University. “It has preserved a unique history of different ethnic groups and has given people the opportunity to look at the roots of our various cultures' music," says Kayastha, who also believes in this digital age, where music can easily be produced through applications and different technologies, there is more role for the music museum to take.

"In regards to museology and academic approach, I see this event as Kathmandu University running short of foresight because they could have benefitted from a symbiotic relation given that they are both music institutions," says Kayastha. "It's sad that they didn't think about a partnership."

But despite its significance and its persistent, careful activities, Kadel's music museum still is less known and shares the same fate as many other museums in the country. It is easily overlooked in a fast-paced modern world, while its development has largely failed outreach and promotion. This also reasons why Kadel didn't see any support from the public during his court case. Many are yet to understand the museum's work, and how museums are an educational space, says Kadel.

"We were not able to promote the work we were doing as resourcefully as many other institutions do in this age. Our weaknesses failed us, despite the work we have done," says Kadel.

But it isn't just the museum's lack of visibility that has cost them their future. According to Rajendra Maharjan, who teaches Newa musical instruments, the government has always overlooked music, musicology and music education. The few efforts that have been happening to conserve traditional musical practices are happening independently, rather than with government support, he says. "There are people who are studying the dhime in Germany, whereas dhime is a traditional Nepali folk instrument. Now the question is: why haven't we been able to explore such an opportunity in the country? Why do people have to go out to learn one's own ethnic instruments?" says Maharjan. "And this is why Kadel didn't get enough support, because our system fails to understand what music contributes to cultures."

In Kadel's case, the government has made efforts to support the institution with its relocation. "We acknowledge that the music museum's work to conserve Nepal's musical instruments is important and Kadel has already collected over 1,300 kinds of musical instruments from across the country. And that is admirable," says Yogesh Bhattarai, Minister of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation. "But when we tried to arrange for a space in the National Museum, he was not convinced. We are still ready to collaborate, but we can't force someone to make their decision," he said to Post over the phone.

Kadel says that as proposed by the Ministry, he had visited the National Museum at Chhauni. But even after several discussions with Jayaram Shrestha, the museum's chief, who offered Kadel space in Chhauni museum’s interior hall, he couldn’t see the relocation fruitful for his museum.

"It looked like I was given space for display purposes, but the main purposes of the museum such as research programmes, and musical festivals and sessions didn't seem to be in the picture. There were many questions: what about my research team, what about the musical training?" says Kadel. "Our museum has been more live; it hasn't just been about collecting things, we even allow students to play the sarangi that is displayed at the museum," he says.

While things still look grim for the museum, Kadel recently won the Nikkei Asia Prize for his endeavour with the folk music museum. With the prize money, he hopes to find shelter for his museum. "I am thinking of saving the prize money from the award to find a place for the museum. Although it's not that much, I still need to see where I can take this museum,” he says.

For now, he is busy preparing for a temporary exhibition with some of the museum's instruments at Hanumandhoka Durbar Museum—until he finds another space to relocate his museum. “I am not certain about what will happen, but I will keep continuing this journey. That is for sure," he says.

22.84°C Kathmandu

22.84°C Kathmandu