Culture & Lifestyle

Postcards from Nepal: Meet the man who showcased the country to the world

Mani Lama has spent more than 60 years of his life taking photos, and to this day, remains enchanted with photography.

Tsering Ngodup Lama

Mani Lama may be 73, but he looks no older than someone in his 50s. It’s not just his face that belies his age. When he walks—which he does a lot—he does so briskly. Tell him he looks young for his age and Lama will thank you with a coy smile. He credits his physical fitness to years of daily yoga and his love for walking.

“I feel very fortunate to have lived my whole life so close to the stupa,” says Lama, whose favourite place to walk around is Boudha, also his home.

His family’s connection with the iconic site is more than a century old. Lama’s great-great-grandfather was Taipo Shing, also known as the first Chiniya Lama, who was the Prime Minister-assigned caretaker of Boudhanath and Swayambhunath stupas and Lumbini.

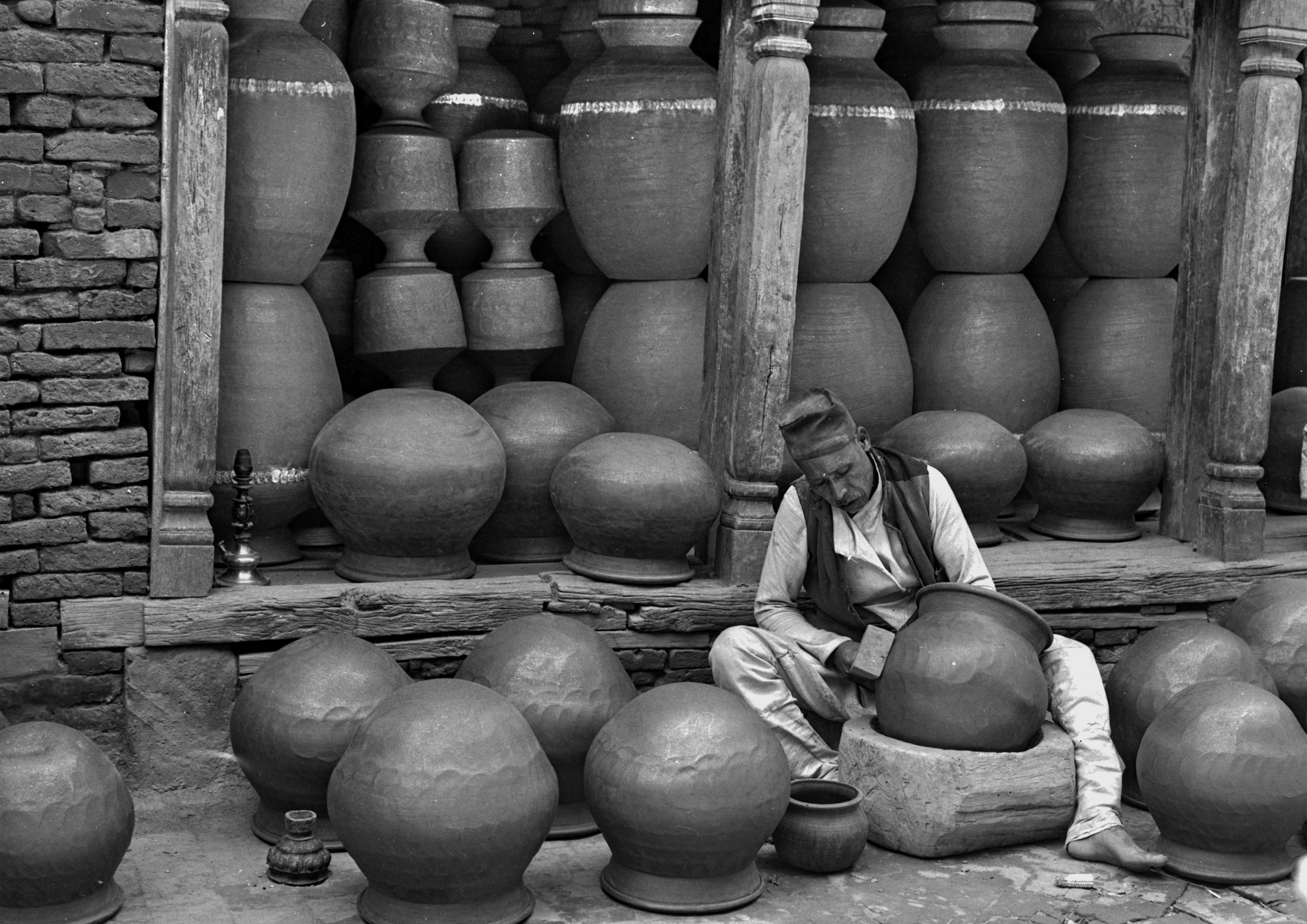

Lama might be known for his lineage in the neighbourhood, but outside the area, he is known for his photography. He is best known for his postcards of Nepal, and has published a coffee-table book called Nepal: The Himalayan Kingdom. He is currently working on another book, on Boudha’s restoration and reconstruction.

Lama has been passionate about photography since he was 12, when he received his first camera—a Kodak box camera. To buy camera rolls and develop films, Lama used to walk a little over an hour to the other side of town, to New Road.

“It was the 60s, and there was no option but to walk across town from Boudha,” says Lama. While his first camera sparked his obsession, what left Lama deeply impressed was his Exakta, also a gift from his father. The camera had a telephoto lens attached to it, which Lama says blew his mind when he first began using it.

While photography has been Lama’s lifelong passion, he has ventured into other avenues—he’s run a few businesses, including a darkroom studio and gallery. Oddly enough, he even has a tick named after him. While working as a lab assistant for two American researchers in 1969, Lama discovered a new genus of tick in Upper Mustang, which was later dubbed the Anomalaya Lama Tick.

But if things had gone according to plan, Lama might have ended up as an agriculture officer with the Nepal government. In 1970, he went to the US to study agriculture.

In 1975, he returned to Nepal with an agricultural degree and started applying for work. “There were jobs I was qualified for, but nobody was willing to hire a guy with Lama for a surname,” he says. “Cronyism was rampant.”

After two years of failed applications, he drifted towards photography. By the early 80s, Lama was running a successful postcard business.

“Postcards in the country then were mostly vertical photos of mountains and monuments. The paper quality of postcards was also bad. I saw an opportunity, so I started taking photos and had them printed in Singapore, with much better print and paper quality,” says Lama. The postcards sold like hotcakes, and he eventually printed them in the hundreds of thousands in Singapore and imported them home.

However, India’s 1989 blockade and the 1990 People’s Movement had an especially negative impact on his business.

“Tourists, who were my main customers, stopped visiting Nepal, and the business died a slow death,” says Lama. “The key is to learn to let go and not hold onto things.”

In 1991, Lama printed his last batch of postcards. By then, his work had become well-known among Kathmandu’s expat community. With his business no longer running, he started applying for freelance projects with international NGOs in the country. Soon, Lama was travelling all over the country, and abroad, as a freelance photographer.

In his nearly 60 years of photography, Lama has dabbled in different genres of photography—landscape, portrait, festival, street. But is there a genre of photography he won’t sink his teeth into? Lama says without second thought: “Weddings. I have done it a few times, but the way wedding attendees disrespect photographers was something I found deeply repulsive.”

Like many photographers of his time, Lama grew up using cameras with rolls and developing in dark rooms. Three decades later, most of his work is digital.

Lama admits that relearning how to use DSLR cameras wasn’t easy. But he reached out to his friends who were more familiar with digital photography, some of whom were his juniors.

“I keep telling younger photographers they should never hesitate to ask what you don’t know,” says Lama. “I remember being nervous when I first started using DSLR cameras for my assignments and I was worried that I wouldn’t do a good job.”

When it comes to the extent photographers can now modify photos in post-production, Lama’s face lights up with a child-like sense of wonderment.

“Isn’t it amazing what Photoshop and other photography apps allow photographers to do with their photos? I keep tinkering around with different photography apps on my phone, and I am often left amazed,” he says before he takes out his phone and plays an ad hoc clip he made earlier, of Chinese opera dancers dancing near the stupa. “It’s amazing,” he says, visibly baffled by technology.

With cameras becoming increasingly affordable and phone-based camera technology improving, professionals no longer have exclusive reign. The number of people using cameras is more than ever, and people now have access to more photos than ever. Lama says the steep rise in the number of amateur photographers hasn’t made life harder for professionals though. Quality work, he says, will always be appreciated.

“The only major difference I feel between then and now is that there are just too many photographers,” says Lama. “When I was growing up, there were only a handful of outstanding photographers. But now, with so many photographers, it’s hard to know who’s doing what.”

Lama’s current book took him 18 months to pull together, and it surrounds Boudhanath Stupa’s reconstruction following 2015’s earthquakes. The book is nearing completion and, according to Lama, will be published in November. It will feature several photographers, who have donated their photos to the project, and the proceeds from the book will go to the maintenance of the stupa. “It’s our way of giving back to the community,” he says.

Lama has travelled every district in Nepal, except Mugu, and his work has taken him all around the world. Despite spending most of his adult life lugging cameras around, Lama, to this day, remains curious and willing to learn new tricks and techniques. He is hungry, he says, and wants to capture pictures and spread his knowledge of photography to those willing to listen.

“I don’t think it’s just my skills that got me where I am in this field,” he says. “You may have the best skills, but if you have a terrible personality, it won’t get you very far.”

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu