Culture & Lifestyle

Chhauni museum is being refurbished, but will it meet international standards?

Nepal’s National Museum has worked on meeting many issues but it is yet to address issues of storage and security..jpg&w=900&height=601)

Alisha Sijapati

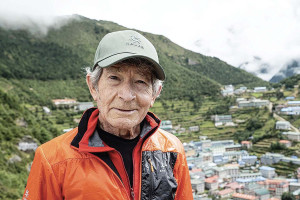

Dinesh Shrestha has worked at the National Museum of Nepal since 1988. For the past 30 years, he has been sitting at the ticket counter from 10 am every day. The wrinkles etched on his face tell us of the years he has dedicated taking care of the museum.

In the decades that he’s spent at the museum, Shrestha says he has seen both the good and the bad, the ups and downs the museum has gone through. “I meet people from all levels here—from students to researchers and even those who come on dates—I have seen it all,” says Shrestha.

While the museum’s management has always been inefficient, and the disastrous 2015 earthquake pummeled the historical building, which was once Bhimsen Thapa’s residence, refurbishment efforts are penned for completion soon, providing an opportunity for the National Museum to reach ‘international standards’. However, what exactly that means is still a topic of discussion.

The National Museum, established in 1928, has always been known as an ‘encyclopedia’, says Swosti Rajbhandari, lecturer of Museum Studies at Lumbini Buddhist University. It stood out in comparison to other museums in the Valley because of its wide range of collections from iconography to ethnography, she says.

Spread over 44 ropanis of land, the museum has three buildings—the historical (Bhimsen Thapa) building, Juddha Jatiya Kalasala and Buddhist Art Gallery.

The Natural History gallery has taxidermied animals along with dolls that represent different castes and creeds. Artefacts that are displayed in the museums include sculptures that date back to Lichhavi and Malla periods and Buddha artefacts that are more than a thousand years old. Since the 2015 earthquake, however, the building’s upper floor that housed arms and ammunition, historical coins, and collections of different artefacts from the Shah and Rana rulers has been shut indefinitely and is undergoing reconstruction work.

Despite the assortment of artefacts the museum has, which comes to be over 28,000, whether it meets international standards is still up for debate. “Our museums definitely do represent the culture and heritage of our country, but it certainly lacks the museology standards followed all over the world,” says Rajbhandari.

And visitors feel that lack of standard. A Hetauda-based teacher Bhola Chalise was left disappointed during his visit to the museum. “There is nothing really new to learn from our museums,” Chalise says. Chalise believed museums should reflect Nepal’s history, culture and heritage.

“What can future generations learn about our country? How can only old artefacts represent our country’s history and heritage in today’s society? A lot has to be done,” says Chalise.

.jpg)

Sabin Dhakal, a regular at the museum, who came to visit the museum with his son, seemed to know about everything that was on display. While his son enjoyed looking at the dolls and the taxidermied animals, Dhakal failed to garner his son’s attention in the other two museums that involved more historical sculptures of various Hindu or Buddhist gods and goddesses.

“I don’t know what should be displayed in the museum but I wish it would be something that would be of a learning experience to my seven-year-old kid,” says Dhakal.

To avoid this from happening, museums should keep rotating the artefacts on display. For example, even though the Chhauni museum has over 28,000 artefacts, it displays only five percent of all the treasures it has accumulated. “If you go to museums abroad, they don’t put everything on display, they change artefacts over the years and that’s what we aim to do as well,” says Jayaram Shrestha, museum chief of the National Museum.

Rajbhandari says it’s also a good idea to conduct temporary exhibitions more often and communicate effectively with visitors through media. Even improvement of simple things such as websites, promotional campaigns and tourist-centric information will help better engage the public with the items on display.

Stefanie Lotter, senior teaching fellow at the Department of Anthropology at SOAS University of London, in an email interview says, “There is no ideal museum. Nepal’s diverse museum landscape is still developing—it focuses more on local visitors and not just tourists. Museums in other places—when they are very good—engage with both source communities and foreign visitors.”

.jpg)

One of the better-kept museums in the Valley is perhaps the Patan Museum. Chaunni museum’s Shrestha says he is “envious” of Patan Museum’s growth. “We too strive to become better, but neither are we autonomous nor do we have the kind of budget to come at par with them,” says Shrestha.

Talking about the reopening of the first floor of the Bhimsen building, authorities say repair works are almost complete. “We are already done with the reconstruction part, now it’s time to settle the interiors, which will take less than a year for a relaunch,” said museum chief Shrestha. He said he hoped visitors, locals or foreigners, would take back some valuable information about our country’s culture and heritage.

Rajesh Pariyal, who has been working as a chronologist in the National Museum for the past three years, says, “We have a very good storage system, every artefact from woods, metals and textiles should be preserved according to the temperature it is suitable in.”

Museums around the world cater to very different technicalities to control their environment, says Lotter. In the absence of such required temperature standards, artefacts such as textiles should not be on display; instead, museums can focus on more robust items such as stone and wood. “You can see some damages due to exposure to light in the Natural History collection in the National Museum,” says Lotter.

However, she further mentions that if museums were to display textiles without damaging it, they would have to rotate exhibits every three months. This is a challenge for any museum, even one that has the resources—but for one without a modern conservation department and the ability to adjust proper lighting, the task to exhibit textiles is virtually impossible. She says that this may be one of the reasons why those items are less on display.

Apart from managing temperature, museums also have to take great care of the security of valuable artefacts. This is another aspect that seems to be lacking in the National Museum, deterring it from obtaining ‘international standards’. In 1995, some of the artefacts from then Mahendra Museum—a part of the national museum—were robbed. Many valuables were retrieved later, only to be robbed again a year after its launch. Thereafter, the artefacts were moved to Basantapur Durbar Square Museum and the Mahendra Museum was renamed Buddhist Art Gallery.

Lotter says the country can learn from other countries to see what the international standard is. “There is a lot that can be learned across the world. Museums in Nepal don’t yet have large collections. For theft prevention, collection management systems and maintaining catalogues according to international standard should be kept,” Lotter says.

Shrestha says that lack of financial resources is creating roadblocks for the museum’s development, including security and preservation of its artefacts. The museum has manual security systems—CCTV cameras and guards—which need to be upgraded to laser light security system and other technologically advanced systems. “There is only so much I could do with the yearly budget we get, and these systems aren’t affordable,” he says.

The National Museum received over Rs 30 million this fiscal year. While most of the budget is distributed to its 58 employees, the rest goes into preserving and maintaining artefact storage and renovations—leaving very little for further improvements, according to museum chief Jayaram Shrestha.

Lumbini Buddhist University lecturer Rajbhandari says this lack of focus on museum upkeeping is because the government’s priorities lie elsewhere. “We come from a developing country where the focus is more on humanitarian development but ideally humanitarian development should go hand-in-hand with cultural development too, but there is a lack of cultural understanding here,” Rajbhandari says.

As a case in point, she mentions how the government had planned to open five regional museums in many provinces, but the plan is still just stuck at three. “We need students to learn about museums and their benefits. They need proper guidance for building their knowledge.”

“For instance, our museums should learn one thing or two from international museums like the Louvre, British museums and others, they have such well-articulated websites, we need something like that too,” she says.

The situation has slowly improved for the country’s first public museum. And the museum chief is confident that someday the museum will match standards of international museums. But for his dreams to manifest, there is still a long way to go.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

23.12°C Kathmandu

23.12°C Kathmandu

.JPG&w=300&height=200)