Culture & Lifestyle

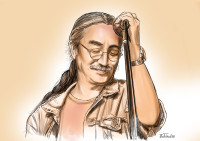

Sabitra Bhandari: No South Asian defence can keep up with me

The star striker talks about how she went from playing sock ball to becoming Nepal’s highest scoring woman footballer.

Pranaya SJB Rana

She’s swift and agile, dodging defenders with an almost preternatural ability to tell where they’re going next. She weaves in and out and in one split second, a golden window, she shoots. The ball finds the back of the net and Sabitra ‘Samba’ Bhandari adds another goal to her tally.

Bhandari is an exceptional footballer, a striker with skill, speed and sight. And since joining the Nepali national women’s football team in 2014, she’s quickly gone on to become Nepal’s star striker with an uncanny knack for scoring goals. In December, at the South Asian Games, she became the highest scoring Nepali woman footballer with 38 goals, beating Anu Lama’s record of 35.

How does it feel to be the all-time leading scorer, I ask.

“I feel like I've made history,” she says.

When we meet at the De Machaan Restaurant in Bakhundole, Bhandari has just returned from India, where she plays in the Indian Women’s League for Gokulam Kerala FC. She scored 16 goals this league, becoming, once again, the highest scorer.

Her hair is cropped short in her trademark style and she’s in pants and a jacket. We sit down to talk and she orders a juice and a fruit platter. Bhandari plays for the Armed Police Force women’s club in the national league and she has training to go to in an hour. She doesn’t want coffee, but she agrees to some chicken.

I ask her to start from the beginning—how did she start playing football?

“I was always crazy about football. I think I was born to play football,” she says.

She grew up in Simpani in Lamjung, in a large family of four sisters and two brothers, and also a grandmother. Her father was a health post official and didn’t always have enough money.

“I never had proper gear or boots or even a ball. I grew up playing football with a ball made out of socks,” she says. “But it is because of the lessons that that sock ball taught me that I'm where I am today.”

Since none of the girls played football, she always ended up playing with the boys from the village. And that, of course, got everybody talking. They did what any conservative society does—go to her parents and tell them to be careful lest she bring disrespect onto them and the village.

“My father and mother tried to discourage me from playing with the boys but I managed to convince them,” says Bhandari. “They always trusted me.”

Whenever she played football with the boys, she played as rough and tumble as they did, not afraid to tackle and push. After all, she had grown up doing all the things that men traditionally did around the house. She ploughed the fields and slaughtered the chicken. At age 15, her brothers even encouraged her to slaughter a goat at Dashain, saying why that should be the sole province of men.

“At that time, I was in a school that didn’t have any sports, so I convinced my parents to send me to another school a little far away that did,” she says. “In ninth grade, I moved to Ganesh Secondary School but unfortunately, they only had volleyball.”

But being the intrepid sportsperson she is, Bhandari joined the volleyball and competed in the President’s Running Shield, a regional sports tournament organised by the Sports Ministry. She got a chance to come to Pokhara and play at the regional-level representing Lamjung.

“We didn't win but when I came back to the village, people appreciated that I had represented the district. Some of my teachers even gave me some money,” she says. “It was then I realised that you could get respect and even earn some money playing sports.”

Bhandari’s big break really came when she was 16, when she got together a motley crew of her classmates for the women’s football tournament in Ghale Gaun. There were national league players at the tournament and she really wanted to give them a show. That was also the first time that she wore boots to play football.

“I borrowed a pair from some boys but they were too big so ultimately I had to play barefoot,” she says. “I was more comfortable playing barefoot anyway.”

She scored 9 goals in that tournament, the most for any player, and caught the attention of national referee Sukra Lama. He took her number and asked if she’d like to come to Kathmandu to try out for the Armed Police Force team.

“In May 2014, after finishing up the planting season, I came to Kathmandu,” says Bhandari. “My mother had given me Rs5000 and with that, I bought a pair of boots and a pair of sports shoes.”

Those were her first pairs of sporting gear.

But Kathmandu is an expensive city and she only had Rs1,500 left. She was staying with cousins, one of whom even helped her out with a fake student ID card so she could get a discount on the bus ride from Banasthali to the APF training centre in Halchowk. It would be a Rs10 ride with the ID card but Rs10 would also buy her a banana, so she chose to walk.

The Armed Police Force team put her into training immediately, as two of their star players were out on ‘missions’ and they needed a striker.

“I had never trained before so when I went to play with senior players, I felt hopeless,” she says. “I had stamina and I could do endurance training but I was bad at ball control. But they needed a striker and I needed to make my dream come true.”

She trained for a month and the APF signed her on a contract for Rs5,000, which would eventually be raised to Rs8,000. She was also trained and inducted into the force as a constable.

It was a relatively small investment but it paid off in a big way. In her debut match against the Nepal Army, she scored the single goal that won the match.

“They thought that we were weak because Jamuna [Gurung] and Anu [Lama] didi were both absent, but when I scored a header goal and we won the match, they took notice,” she says.

It seems everyone took notice. That same year, in 2014, she was called up to the national women’s team and debuted internationally at Third SAFF (South Asian Football Federation) Championship in Pakistan. Again, in her first international debut, she scored a goal.

“First game, first touch,” she says.

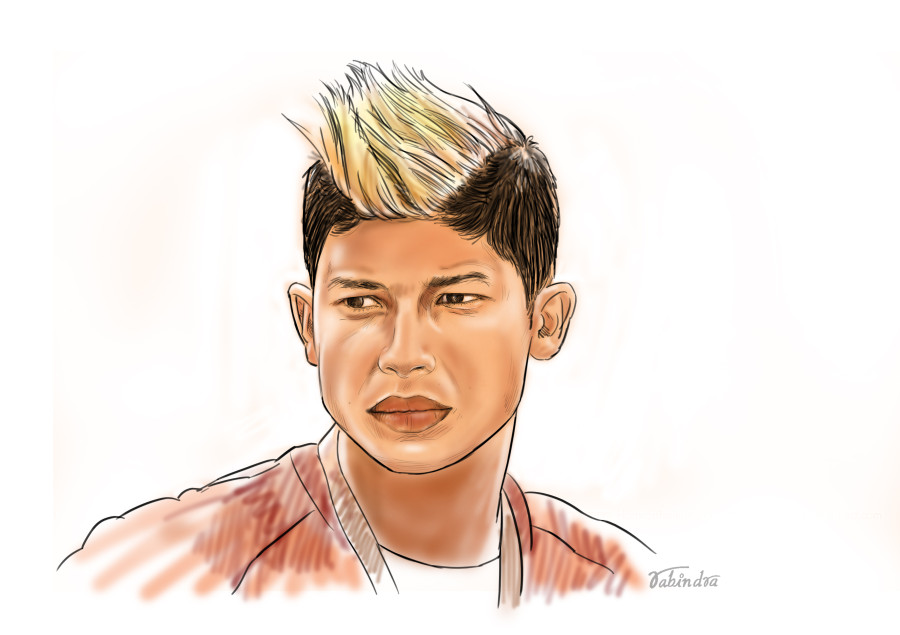

That was also when she acquired her trademarks—her nickname and her changing hairstyles.

“I always had short hair but it was only after joining the APF team that I started to style it,” she says. “I always wanted to style it but people would talk in the village.”

And it was her teammates who also started calling her Samba, as Sabitra was a little too big of a mouthful on the field.

Since then, Samba’s graph has only been rising. She’s become an integral member of the APF team and regularly scores dozens of goals every season. In 2019, she was signed by Sethu FC, a club based in Tamil Nadu. After playing one season for Sethu, she switched to Gokulam Kerala this year.

“In India, all of the teams are tough,” she says. “Here in Nepal, except for the three departmental [Nepal Police, APF and Nepal Army] teams, we don't really have to prepare for the others.”

Playing in India has only made her game better, as going head-to-head with tough teams helps to build skill. That’s what Nepali football needs, she says.

“Women's football needs more exposure, internationally and domestically,” she says. “There are not enough leagues for us to play in so a lot of players are going abroad. In India, they have state leagues and more opportunities to play throughout the year. These leagues and tournaments are opportunities to identify new players and build your game.”

It is possibly because of the state-level tournaments and the age-wise tournaments that the Indian national team consistently beats Nepal.

“We have the ability to win but they [India] have teamwork,” says Bhandari. “We haven't been able to work effectively as a team on the field. Our team is not balanced either. Small mistakes are costing us the game.”

There’s a lot that Nepal can learn from India, not least of all is the value that they place on women’s sports. They pay their athletes well and the prize pools are significant. In Nepal, the winning pool for the men’s football league is more than Rs 10 million while it is Rs 150,000 for the women, says Bhandari.

But Bhandari also has a more personal reason for looking up to India—she wants to be like Bala Devi, an Indian national team player and a member of the Rangers, a Scottish football team.

“My dream is to play in a European league,” she says. “I have speed and I have the finishing. No South Asian defence can keep up with me.”

ON THE MENU

De Machaan, Bakhundole

AmericanoX2: Rs460

Fresh juice: Rs180

Fruit saladX3: Rs1,050

Timmur chickenX2: Rs1,700

14.38°C Kathmandu

14.38°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)