Visual Stories

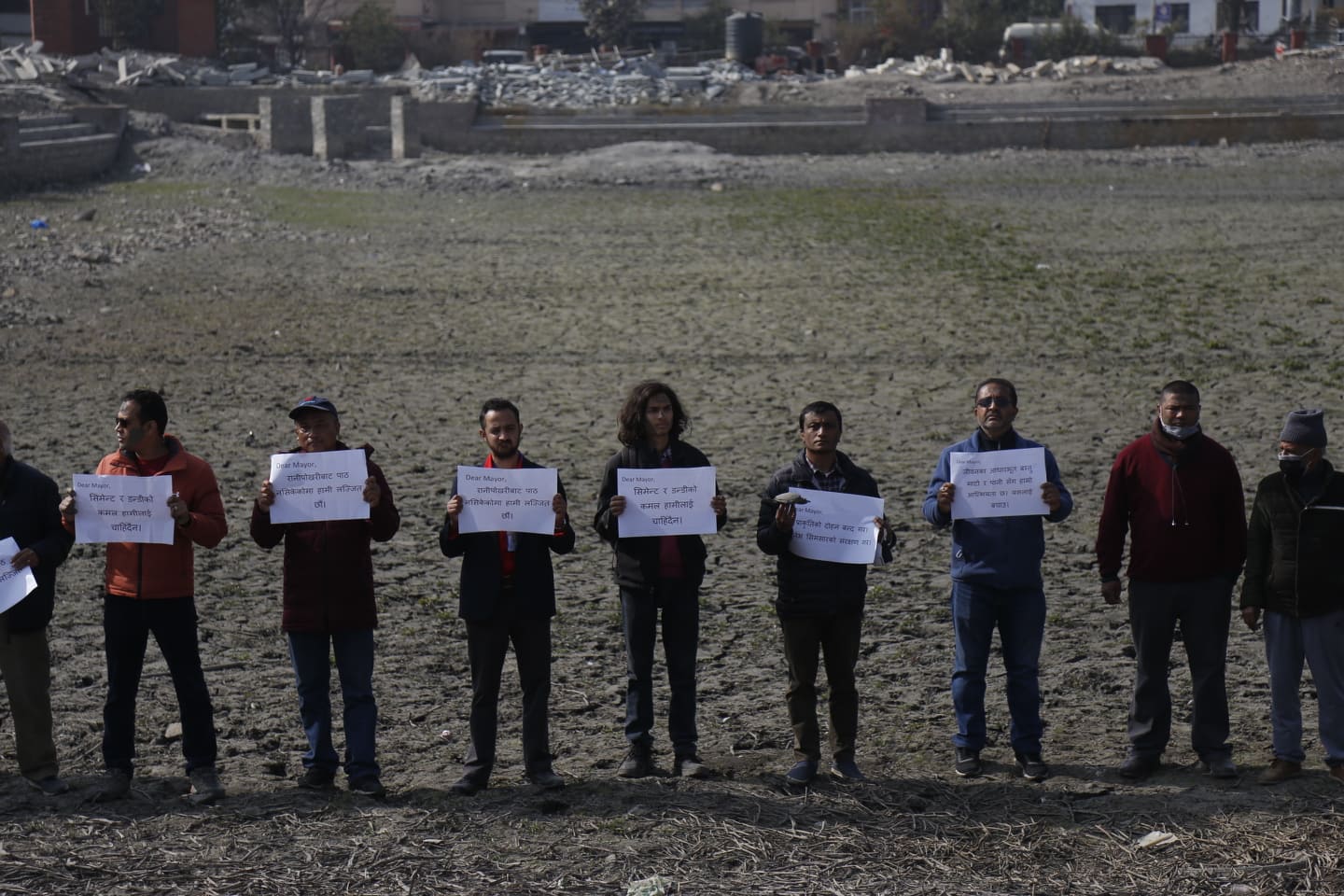

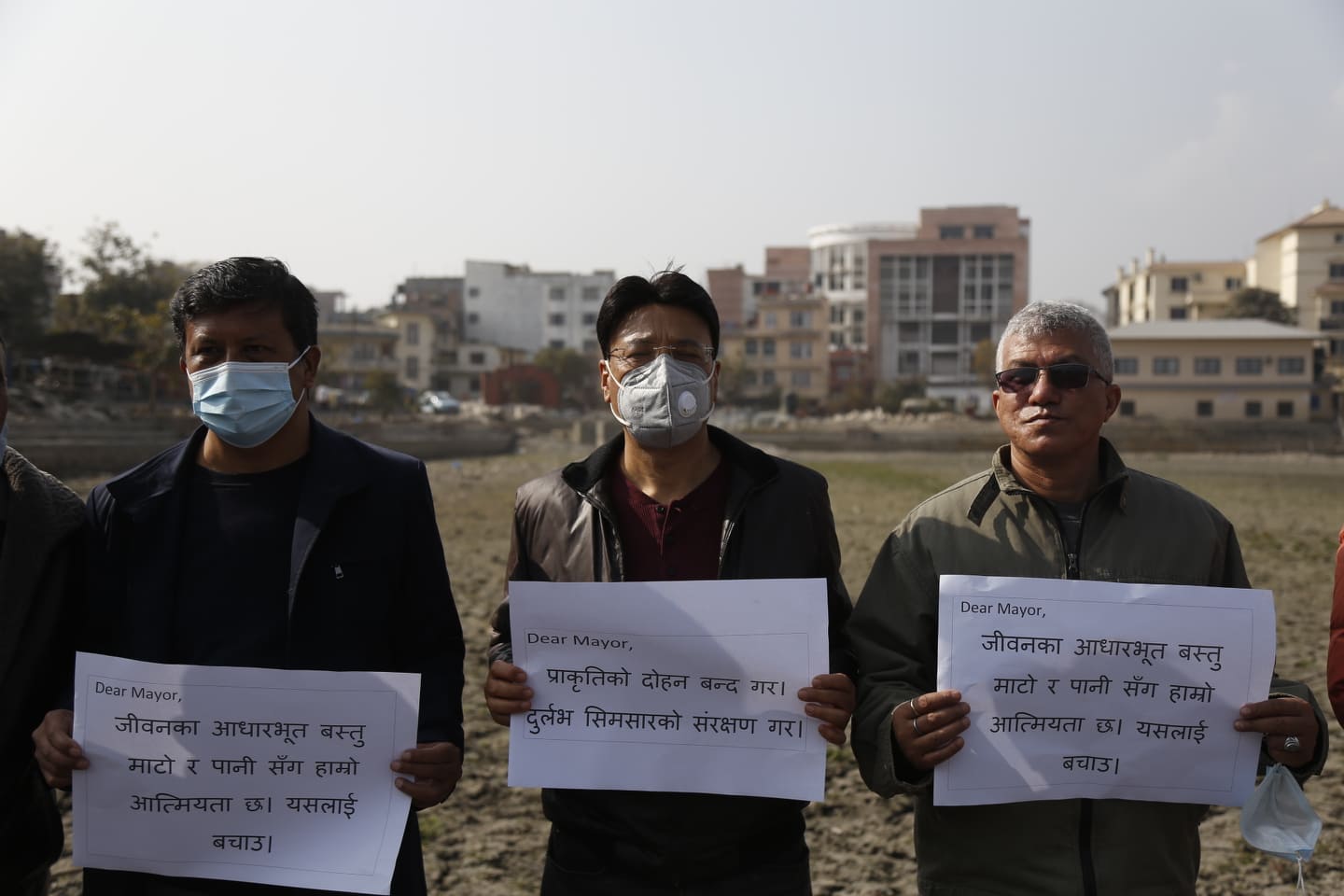

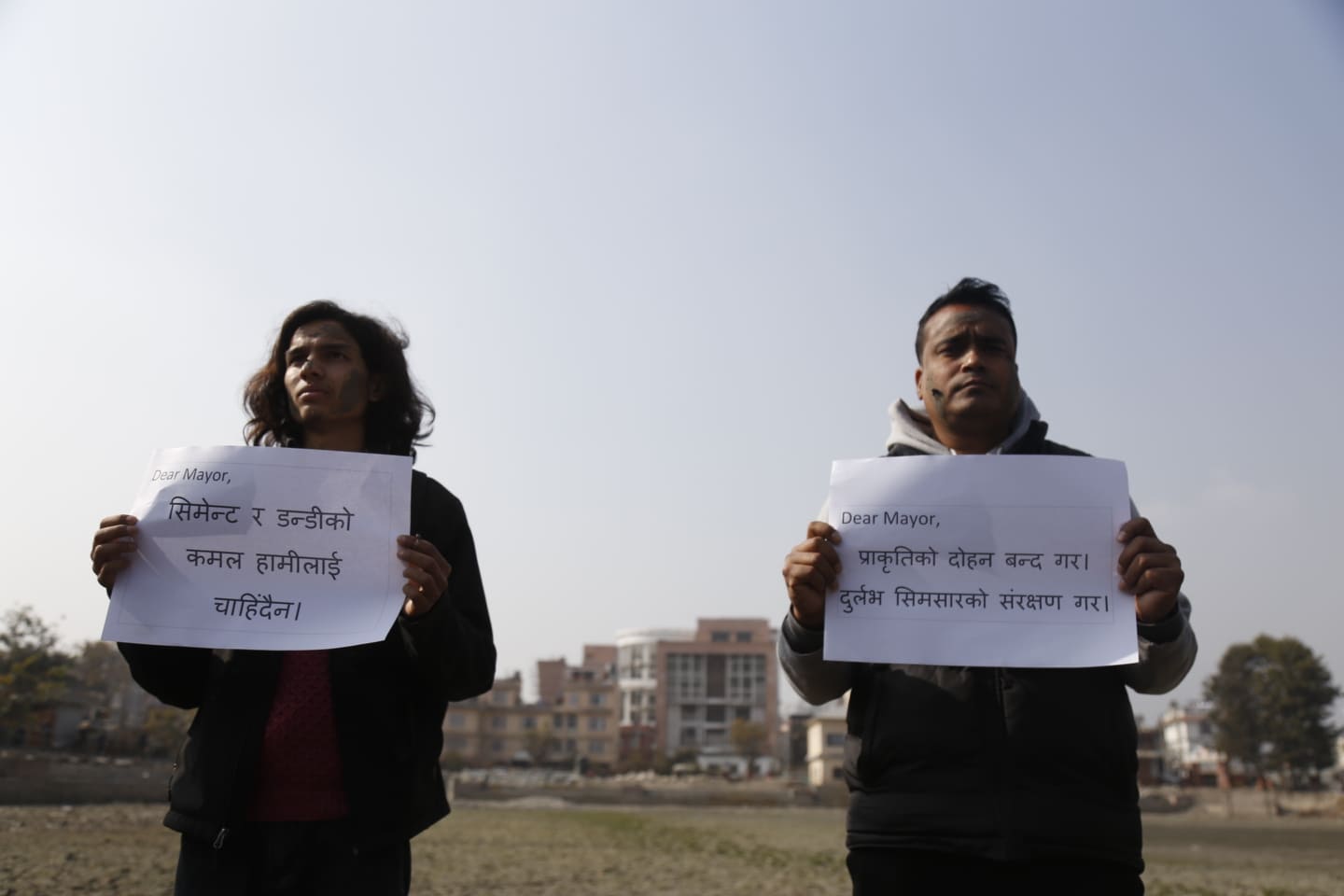

Heritage conservationists carry out symbolic protest for conservation of Kamal Pokhari

The centuries-old pond in Kathmandu is being restored by the Kathmandu Metropolitan City as a recreation centre with small artificial ponds at four corners and a fountain at the centre.

Post Report

Heritage conservationists on Friday carried out a symbolic protest, demanding the conservation of Kamal Pokhari, a centuries-old pond in Kathmandu, which is being restored by the Kathmandu Metropolitan City as a recreation centre with small artificial ponds at four corners and a fountain at the centre.

The protesters painted their faces with the mud from the pond and said that it’s a shame that the authorities have failed to learn a lesson from the restoration work of Rani Pokhari and protect Kamal Pokhari.

[EDITORIAL: A tale of two ponds]

The pond has been emptied of water to carry out the restoration work.

Though many local residents of the area are happy with the ongoing restoration work, hydrology experts say the plan noticeably fails in understanding the purpose of a pond and that the general public is unaware of the loss the ambitious beautification project will cost: ecological imbalance.

“The main purpose of a pond is to recharge groundwater; it is to maintain the temperature of the surrounding and to mitigate urban floods in the area,” Prakash Amatya, a water conservationist, had told the Post in December, last year. “But this whole project disregards these purposes and focuses only on the beautification to develop it as a recreational space.”

Kathmandu Metropolitan City hopes to complete the restoration by May this year.

According to authorities of the restoration project, the ongoing first phase of the project focuses primarily on the beautification of Kamal Pokhari.

“We are working to beautify Kamal Pokhari and we have not used any concrete,” Prem B Shrestha, engineer and project coordinator of the Kamal Pokhari restoration project, had earlier told the Post.

Amatya, however, had refuted this claim saying concrete has been used below the water.

Environmentalists and heritage activists remain unconvinced with the approach of the restoration.

They fear that Kamal Pokhari is going the Rani Pokhari way.

“The Rani Pokhari we now see only serves the purpose of beauty, it does not serve the large purpose it once used to, of mitigating floods and maintaining the water cycle of the area,” said Amatya. “If we don’t raise our voices now, Kamal Pokhari is going to be next. A pond’s function goes beyond its social aspect, it serves for the balance of nature.”

For long, environmentalists have been challenging the government’s way of restoring ponds in the country. When a boring system was placed in Rani Pokhari to replenish the pond, heritage activists and water experts demanded the authorities remove the deep wells from the pond for months.

But the authorities of the project have not conducted any detailed study of the area to address its historicity; rather they have been approaching the pond only as a mere development project to appease the locals of the area, say experts and researchers.

Kamal Pokhari over the years has also suffered with encroachment of its areas. Years back Kamal Pokhari was spread over 40 ropanis, said the people the Post talked with in December last year. But with years, the size of the pond has shrunk.

As Kathmandu continues to urbanise rapidly, open spaces like Kamal Pokhari will be integral to keep nature in balance, conservationists say.

Post photojournalist Kabin Adhikari took some photos of the protest.

21.01°C Kathmandu

21.01°C Kathmandu