Visual Stories

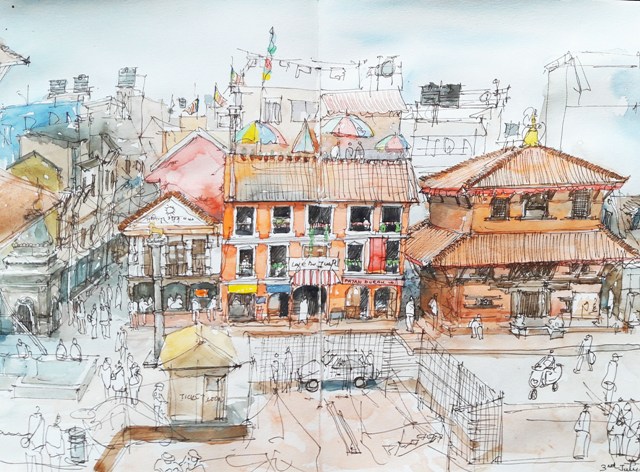

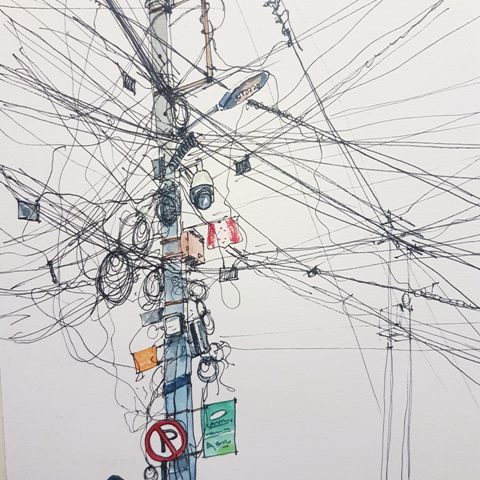

Embracing the city of muddy roads and tangled wires

Sketching the life, or lack thereof, that has come to define Kathmandu.

Kamal K Maharjan

We were waiting for our turn to board our flight. I was flying back to Kathmandu after staying a few days in Biratnagar. Sitting inside the air-conditioned waiting room, I was watching the air marshal direct the aircraft we were supposed to take. While the plane was making its way to its designated track, the sweat from the air marshal’s forehead was also running downwards towards his cheek and journeying to his collar. It was nothing out of ordinary given the outside temperature was 35 degrees.

I took my window seat, which I had requested beforehand. Many prefer an aisle seat, but I still enjoy the view of the ground from the air. The choice didn’t disappoint me--I revelled at the view of the vastness of Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve. The Koshi River, twisting and turning, must have made through all those narrow ravines and valleys spilling onto the plains of Tarai to finally spread to its size. I wondered how long it must have travelled in order to reach here, and how long will it be travelling, before it merges with the Ganga and eventually the Indian Ocean.

From 25000 feet above the ground, we were flying amongst the dormant clouds. I could see tiny houses and settlements scattered around the terrain and perched up in the hills. Roads danced and swerved graciously connecting these settlements and houses. To the north, I could trace the outline of Gauri Shankar peak through a small opening in the clouds that otherwise completely curtained the view of the range. My eyes were glued to the window, taking everything in.

After about 40 minutes, the aircraft began descending towards Kathmandu. Contrary to the view I had been indulging for the past half an hour, it sharply changed to the concrete cluttering. I couldn’t help myself being overwhelmed by the sheer number of mismatched housed cramped together in this tiny Valley. From above, it looked like a tumour gobbling up the life around it. A tumour that doesn’t show a sign of stopping, and us--a living-breathing part of it.

Born and bred in Patan during the 90s, I have lived through the metamorphosis of this city. The spacious bahas and bahis turned into parking spaces for the towering RCC structures that eventually overtook the cityscape. Once flourishing fertile fields of agricultural yields, it is now a claustrophobic concrete maze of a city, more so, a hostage to the ever-growing and ever-demanding population.

But home has an unerasable imprint on people, even when one may feel like a hostage inside it. Like the Stockholm syndrome, Kathmandu never stops to grow on me. Regardless of how much disdain I feel for its appearance, I start to miss the chaos, that is Kathmandu, whenever I am away for a long time.

When I step inside the concrete maze, I surrender to the place that shelters me even when it has been ripped apart for decades. I have no choice but to embrace this city, like the way it embraces me and many others in its lap.

We cannot overlook what has become of this city. The muddy roads and disarrayed electrical lines have become its integral part. As an artist, it is difficult to refrain from reminiscing on its glory days when I think of Kathmandu. When I sit down with my pen, ink and colours, I think of sketching out paintings like the ones sold in rows of identical art shops around the world heritage sites: a man walking into the distance in a traditional alleyway, carrying a kharpan while women walk in groups wearing haku patasi.

But that wouldn’t be true to the time I live in and the life that is happening around me. If I had lived in the Himalayas, I would have painted the hills and the mountains; if I had lived in the Tarai, I would have painted paddy fields and thatch-roofed houses, but I live in Kathmandu and I sketch the things that are around me.

My sketches are my homage to this time and place, however chaotic it may be. These are my journals to represent my surroundings from this time.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu