Valley

Limited slots at government daycare centres leave working mothers without support

The daycare at Singha Durbar prioritises permanent staff, leaving contractual civil servant mums at a disadvantage.

Aarati Ray

While government offices in Singha Durbar start buzzing with activity starting 10am, Bina (here identified with a pseudonym for privacy concerns) begins her day much earlier at 8:30am. She often works long past the official 5pm closing time.

For the past four years, she has worked as a contractual employee, cleaning offices, making and delivering tea, and handling odd jobs. She toils at the centre of Nepal’s power, yet remains at the margins when it comes to workplace benefits.

Nowhere is this exclusion more painful than in the government-run daycare inside Singha Durbar, a facility she can see but not access.

When Bina was three months pregnant, she would pause outside the daycare, picturing a future where she could work peacefully, her child just a few steps away. But reality hit hard when she was told five months into her pregnancy that the centre was strictly for permanent employees.

With her partner working abroad and no family in Kathmandu, she pleaded for an exception. Each time, she was denied. Left with no choice, she summoned her mother-in-law from the village, knowing it meant leaving her ailing father-in-law without care.

Still, the arrangement is far from ideal. Her body is a reminder of her absent child as her milk leaks through her blouse. “I run to the bathroom, pump the milk, throw it away, and rush back to work. If only my child were in the daycare near me, I wouldn’t have to deprive my child of it.”

One day, when a superior noticed, he said, “If you can’t work well, leave the job.”

Private daycare that costs between Rs13000 to Rs14000 is beyond her means. Her mother-in-law can’t stay forever, and preschools won’t take her child until age three. What then will she do? She has no answer. “No wonder many quit their jobs here after pregnancy,” says Bina.

Bina’s struggle is just a chapter in the story of countless working women in Nepal.

The number of women in Nepal’s workforce, both in government and the private sector, has increased in recent years. According to the Department of Civil Personnel Records, the percentage of women in civil service rose from 13.1 percent in 2010 to 26.5 percent in 2020.

With both parents working in urban nuclear families, the need for childcare facilities has grown.

In response, the government has opened daycare centres in Singha Durbar and Lalitpur. However, these centres are limited in number and accessibility, leaving contractual staff without support.

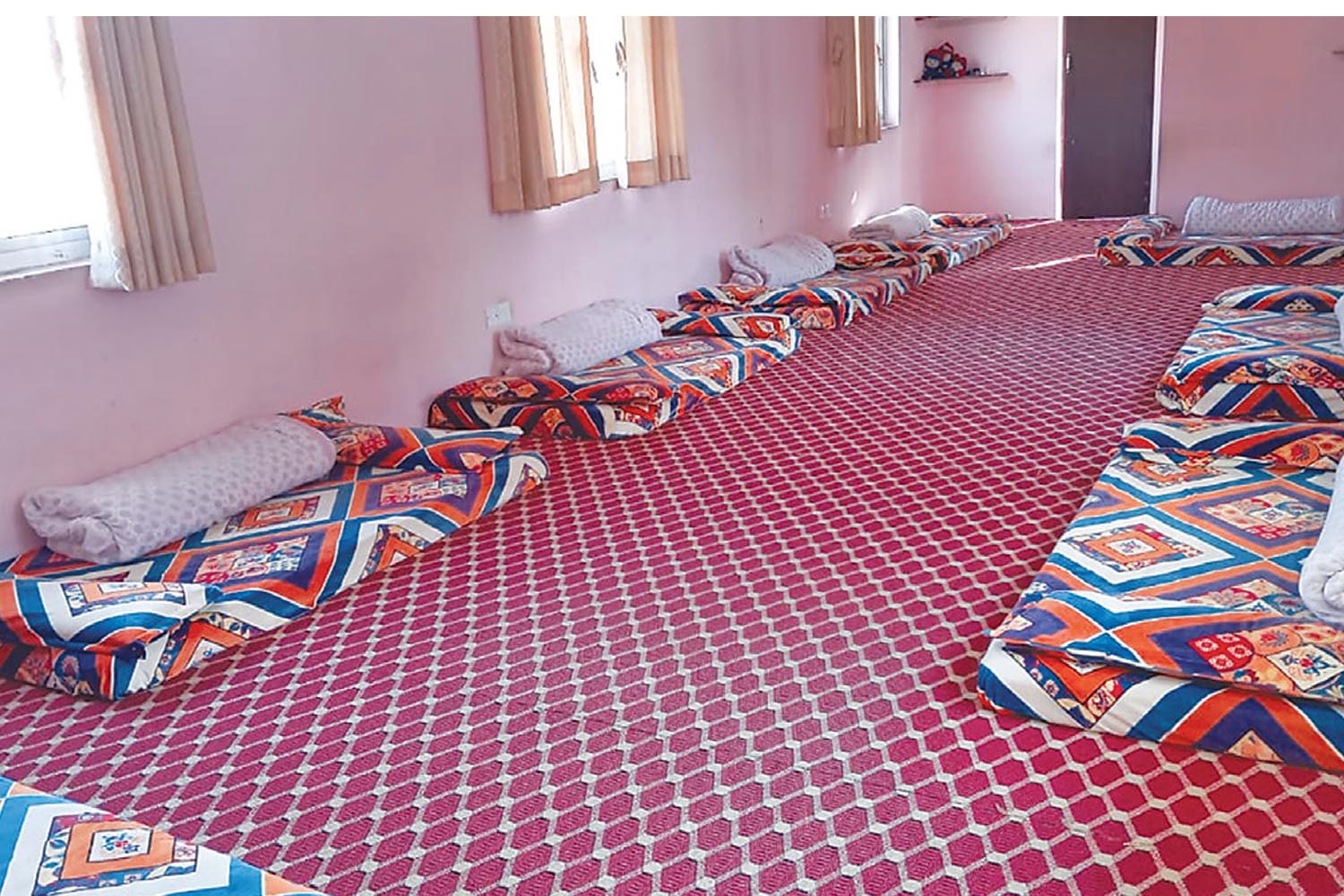

Sangita Ghimire, co-manager of the Singha Durbar daycare, says they can only accommodate 75 children, aged three months to three years.

The demand is far higher, with a constant waiting list of about 40 families. “When a child turns three and leaves, we immediately get calls from ministers and parents on the waiting list, urgently requesting an open spot.”

Under the 2014 “Procedure for Operating the Daycare Centre for Children of Civil Servants within the Singha Durbar Premises,” priority for enrollment is given to: a) single parents who are civil servants, b) couples where both parents are in government service, and c) female civil servants in lower-ranking, non-gazetted positions.

But the prioritisation of non-gazetted positions is limited to paper.

Children of contractual employees were until 2014. As demand from permanent civil servants grew, the Ministry of Women, Children, and Senior Citizens and steering committee instructed that enrollment be limited strictly to permanent employees, says Ghimire.

For some contractual employees, alternative daycare centres provide a solution.

Rita, another contractual worker (office assistant) at Singha Durbar, again identified here with a pseudonym, found a lifeline in the daycare centre operated by the Nepal Police Wives Association at the Kathmandu Valley Traffic Police Office.

While this facility primarily caters to children of traffic police, five spots are allocated for the general public. “Without this daycare, I might have had to leave my job,” Rita says.

Even so, there are limitations.

Unlike Singha Durbar’s daycare, which has separate rooms by age, all children here share one space, increasing the risk of injuries from play and the spread of illnesses. She frequently commutes between Singha Durbar and the traffic police office to breastfeed.

With a monthly childcare fee of Rs4,000 compared to Rs2,700 at Singha Durbar, Rita wishes her child got a spot in Singha Durbar for convenience.

The daycare at the traffic office too gets many requests from contractual civil servants, but its capacity is limited. “It’s heartbreaking to turn away so many mothers in need,” says Pramila Lamichhane, supervisor of Traffic Police daycare.

Lack of daycare facilities is not limited to government offices.

Women in Nepal occupy 42 percent of all roles in surveyed commercial banks compared to 38 percent in Sri Lanka and 18 percent in Bangladesh.

Yet, even in established banks, gender-friendly spaces like breastfeeding rooms or child daycare centres remain rare.

Samjhana Gyawali, an administrative head of digital banking at Rastriya Banijya Bank, struggled to balance work and childcare during her first pregnancy.

It was only after securing a spot at the traffic police daycare for her second child that she realised the critical role such centres play in the retention of working women. “Child daycare facilities should be made mandatory in every organization, whether private or public,” says Gyawali.

NIMB Bank, with over 3,000 employees and 46 percent female staff, has seen steady growth in female representation, says Rajesh Sharma, information officer. “We introduced breastfeeding rooms this year. While opening daycare at every branch is hard, we are considering opening a shared centre at the head office,” he added.

“Yes, more women are working now, but many are forced to leave their jobs due to pregnancy, especially when childcare support is not available,” Gyawali says. “The government and private sector must go beyond hiring quotas. Systemic barriers like lack of daycare force women out of work,” adds Gyawali.

“The government should mandate workplaces to provide daycare facilities. If larger companies cannot do it individually, they can collaborate and ask for tax incentives. Without proper childcare, Nepal may again see a decline in female workforce participation,” says Gyawali.

Chakra Bahadur Budha, spokesperson for the Ministry of Women, Children, and Senior Citizens acknowledges the growing demand. “But we face budget and space constraints. Even regular civil servants struggle to secure daycare slots, let alone contractual employees. In the future, we plan to address this issue through budgetary adjustments.”

Ghimire, however, rebuts the claim of space limits. “There are many empty rooms within Singha Durbar. If space is truly an issue, an alternative daycare facility could be established outside the complex for contractual employees.”

The daycare centre at Singha Durbar always has one or two contractual civil servants asking if their children can be admitted. “They regularly come to us crying for help. In reality, this service is even more vital for contractual staff than it is for regular employees”, adds Ghimire.

“If the steering committee allocates a certain percentage of the quota for contractual civil servants, it would be a great relief for them,” she said.

Rita, the contractual employee, says, “I’ve worked for eight years yet I am denied a spot, but civil servants with less experience get daycare as they’re permanent employees. Many of us have to quit or struggle to balance work and family. I was lucky to get a spot at the traffic police daycare, but others aren’t.”

The need for childcare facilities in Nepal is clear. Whether through expanding government-run centres, incentivising private organisations, or enforcing corporate daycare policies, systemic changes are required. Until then, countless working mothers like Bina will be forced to choose between financial stability and their right to parenthood.

“I might do cleaning and cooking, but I too contribute to the same government. Why is it that those already marginalised and with fewer resources are the ones who get no government help? Is the idea of women’s empowerment and the right to work only for high-ranking officials?” asks Bina.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu