Valley

Solid waste a stinking problem

Sameer Shrestha, an agriculture engineer, has been struggling to manage his household garbage for weeks now. Sacks full of all kinds of waste are stacked outside his house for days as garbage collection is irregular.

Chandan Kumar Mandal

Sameer Shrestha, an agriculture engineer, has been struggling to manage his household garbage for weeks now. Sacks full of all kinds of waste are stacked outside his house for days as garbage collection is irregular.

“It stinks horribly and we don’t have enough space to compost biodegradable waste,” said Shrestha, a resident in Maitidevi, Kathmandu.

Waste management in Kathmandu Valley is a recurring headache. Every monsoon, the road to Sisdole landfill site in Okharpauwa, Nuwakot, is disrupted and trucks are unable to transfer municipal solid waste collected in the Valley.

This year, garbage collection in Kathmandu has been affected since May 23. Piles of garbage have popped up almost everywhere, posing serious public health risks while deteriorating the city’s image.

But the problem of solid waste management looks daunting this time and the condition could worsen even if the monsoon retreats next month because the Sisdole landfill site is expected to be filled to its capacity within three to six months.

Hari Kunwar, chief of the Environment Management Division at the Kathmandu Metropolitan City, said the search for an alternative landfill site is on.

“We have formed a task force to suggest another site for dumping waste generated in the Valley,” said Kunwar.

While municipal authorities look for options to dump solid waste, experts say residents would most likely resort to open burning of garbage, adding to the already severe state of air quality.

“Most of the time, we are only concerned about vehicular emissions, industries and brick kilns. But we tend to forget the intensity of open burning [of waste] and its harmful impacts on public health,” said Bhupendra Das, a PhD scholar with the Central Department of Environmental Science, Tribhuvan University.

Das recently co-authored a report on open burning of waste in the municipalities of Nepal. The report, released earlier this month, reveals that burning waste releases dangerous amount of pollutants into the atmosphere.

Instances of open burning were recorded to be higher in areas where garbage collection vehicles are irregular or absent due to poor road conditions. Also, the burning of waste was found to be higher in the suburbs, where the

frequency of garbage collection is lower, according to the study.

Of the 319 waste piles that were identified during the study, 137 or 43 percent were found to be actively burning in different routes of the urban and suburban areas of the Valley.

The highest open waste burning—0.027 kg per capita per day (kcd) was recorded in Budhanilkantha, followed by Mahalaxmi/Gwarko (0.017 kcd), Lagankhel (0.014 kcd), Baneshwor (0.012 kcd), Bhaktapur suburbs (0.008 kcd), Kalimati/Dallu (0.006 kcd), and Bhaktapur core (0.003 kcd).

With this rate of open waste burning, the report estimates that municipalities in the Valley burn about 7,400 tonnes per year or 20 tonnes of solid waste every day, which is three percent of the total waste produced.

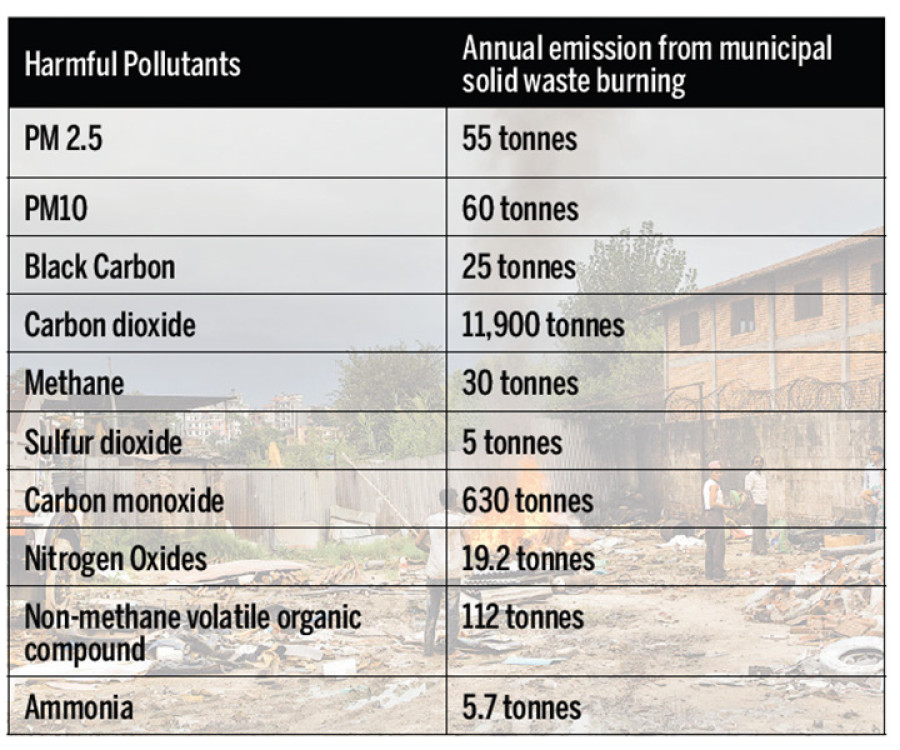

The study calculates that the amount of open burning would emit dangerous amounts of air pollutants—55 tonnes of PM2.5, 60 tonnes of PM10, 25 tonnes of black carbon, 11,900 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2), 30 tonnes of methane, 5 tonnes of sulfur dioxide and 630 tonnes of carbon monoxide, among others.

“These pollutants can have severe impacts on human health and contribute to climate change,” warned Das. “Improving the waste collection mechanism, access to garbage trucks and rickshaws in inner parts of the city and suburban areas, waste segregation at the source, and banning of open burning can be instrumental in stopping the release of these pollutants into the air.”

Various studies point out that nearly 75 percent of the waste produced in the Valley is biodegradable and could easily be composted if segregated at the source. However, separation of waste hasn’t been widely practised in the Valley.

According to environmentalist Bhushan Tuladhar, segregation of waste can be beneficial on environmental and economic fronts while the waste management by finding another dumping site fails to be a sustainable approach.

“After segregation at the source, we can compost the garbage, which can reduce the amount of garbage transferred to the landfill site. Recycling can also prevent the transfer of hazardous waste to the environment,” said Tuladhar, who suggested that private companies should be encouraged to get into waste recycling business by offering them short-term incentives like providing land for composting and recycling.

Doko Recyclers, a private startup operating since July 2016, collects recyclable waste from 70 organisations and 1,800 households in the Valley. In exchange for waste items, which they pick up from the doorstep, they also pay cash to the clients.

“Waste segregation is not a common practise here. Without separating waste, the problem will continue. A large portion of waste has monetary value. Government agencies should also provide training and prepare guidelines for companies working in the waste management sector,” said Mahato, co-founder of Doko Recyclers.

The Solid Waste Management Act-2011 requires local bodies to prescribe separation of solid waste into at least organic and inorganic matters at the source and to encourage public to go for reduction, reuse and recycling of solid waste.

13.26°C Kathmandu

13.26°C Kathmandu