Theater

Traversing forbidden boundaries

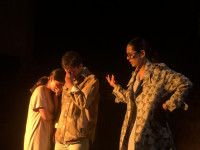

Shilpee Theatre’s new play revolves around a love affair between an older Chhetri woman and a Dalit boy.

Urza Acharya

Sitting at the cafe inside Shilpee around noon, I watched the yard in front of the ‘Gothale’ theatre slowly fill up with people. All of us were here for one thing—to catch the 1 pm show of ‘Bimoksha: The Salvation’. Like me, the crowd was clearly drawn to the play because of its peculiar storyline. Because even on a Saturday noon, the theatre was teeming with people—some aged, while some young.

Bimokshya is a love story. But not the usual kind. It is a play about a love affair between a 45-year-old woman and a 19-year-old man, seen from the past and present. To be more specific, it is a love story about an upper-class Chhetri woman and a Dalit boy.

Saguna Shah plays Muma Hajur, a military wife on her deathbed. Her younger self Rashmi Devi is played by Pabitra Khadka. The young impressionable boy, Kamal Ghimire and later Deep Darnal, is played by a newer face, Sagar Khaki Kami, whereas the older, more cynical version of him is played by the playwright Ghimire Yubaraj. The play is directed by Prabin Khatiwada.

Speaking of the technical aspects of Bimoksha, the mise-en-scene is tastefully put together—the play takes place inside two lavishly furnished rooms. The blocking (the staging of actors in a play) is seamless. One thing that was particularly new and commendable was the use of video projection—projecting on two sides of the stage—to further the background story necessary for the plot. This meant that the audience didn’t need to sit through boring filler scenes, and the production team saved a lot of time and resources.

Bimoksha is a play that moves between the past and the present, symbolised by the two floors on stage. The floor above is the dreamy past, one of love and passion, where the younger versions of Kamal and Rashmi aunty (what Kamal calls her) are deeply in love. But on the floor below, the ambience is much more gloomy, time and age have caused a rift between these past lovers, who see their time together as two completely different things.

Of course, with any play or movie or story about an older woman taking a young lover, it’s always seen as an antithesis. In fact, in a world where it's much more common for an older man to date or marry (or manipulate) a young woman, it’s always ‘a story’ when it's the opposite. But one thing about Bimoksha is that it doesn’t aim to sensationalise. People may walk into the theatre hoping to catch a glimpse of this unusual romance, but they will walk out with much more.

Bimoksha presents us with two different but co-existing realities. One is of Rashmi Devi—an upper-class military wife with a seemingly perfect life. But underneath the perfect facade, she is a victim of oppression and domestic violence. “I saw so much of myself in Rashmi Devi,” says Saguna Shah. She points out that the troubles of women from the upper strata often go unnoticed, as they are assumed to have it all. But in Bimoksha, we see that it’s not that simple. The idea of prestige and capital enforced by others and themselves (as a form of self-policing) may be even more prominent in women from ‘well-off’ families.

The other reality is of Kamal Ghimire, aka Deep Darnal. Deep is a Dalit. When he arrives in the city, Deep, like many other Dalits, is forced to lie about his surname because nobody will rent a flat to him. In a haunting monologue, Ghimire Yubaraj’s Deep, talks about how in the village, people happily wore the clothes made by his grandparents at their wedding, but the makers had to stand far behind and watch the celebration.

Deep talks about how elusive and dangerous this idea of ‘love’ is to him—especially his love for Rashmi Devi because Dalits like him have been forced to jump into a river for choosing to love. Deep is forced to choose between ideology and love. Because with Rashmi Devi, he’s Kamal, but in real life, he’s Deep. Ghimire Yubaraj’s sullen facial expressions and impatient movements across the stage masterfully mirror the dilemma his character is going through.

The younger Kamal/Deep is played by Sagar Khati Kami, who told me that the struggles his character goes through are quite close to real life. Kami plays the younger 19-year-old-deep with a playful innocence, as somebody who is experiencing love for the first time.

However, the play is not without its flaws. Bimoksha falters while portraying the relationship between 45-year-old Rashmi Devi and the 19-year-old Kamal. At one point, it is difficult to figure out where the lover in Rashmi Devi ends and where the mother in her begins. In an intimate moment together, Kamal reveals to Rashmi Aunty that he wants to ‘be inside her womb’, which I found to be particularly too Oedipus-sy. Do women always have to be the nurturer—the giver in a relationship? Just because Rashmi Devi is old and a mother doesn’t mean this role of hers will manifest in her affair as well. In fact, when with Kamal, she takes on a more conventionally masculine role—she smokes and drinks her husband’s whisky. There’s always a notion of connecting a woman’s story to motherhood and showing her as an inherent nurturer and a carer, which may not be true for all women.

I believe that whenever we write as a character, we ourselves aren’t—for instance, when men write women or a Bramhin writes as a Dalit character, there needs to be sensitivity, and there needs to be a lot of research. Only then will be able to bridge the gap between reality (that marginalised people actually live) and perceived reality. It is very easy to depend on stereotypes and generalisations to forward the plot. Director Khatiwada and Ghimire Yubaraj tell me that they took input from both Shah and Kami about their characters. “I wrote this play studying the social and political matters of our time. I see, and I absorb the characters I write from around me,” says Ghimire Yubaraj. However, he modestly admits, “There can never be a complete portrayal.”

Playwright Ghimire, director Khatiwada and the actors all have created a powerful narrative on the nuances of love, caste, gender and power hierarchy. Under the guise of a love story, they show us the different realities and different struggles of people, all fighting for a life of dignity. As the play neared its end, I was reminded of a line from Arundhati Roy’s book ‘God Of Small Things’, which reads: ‘Only that once again they broke the Love Laws. That lay down who should be loved. And how. And how much.’ For Rashmi Devi, loving Deep was her greatest rebellion. But for Deep, the struggle for a life of dignity for himself and others like him outweigh the sweet comfort of romantic love.

—-

Bimoksha: The Salvation

Shilpee Theatre, Battisputali

When: February 28 to April 1

Time: 5:30 pm (Sunday to Friday), closed on Tuesday, additional show at 1 pm on Saturdays

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu