Theater

The simple brilliance of the play ‘Chor ko Swor’

The real beauty of this play lies in the things left unspoken and the things left hidden in plain sight.

Shranup Tandukar

The power of a play, as with other visual forms of art, is its ability to have multifaceted impacts. It can be a source of entertainment, a celebration of culture and traditions, an artful depiction of social issues, or an escape from reality. Once in a while, a play is produced that single-handedly achieves all these things.

‘Chor ko Swor’, a play presented by Artmandu Nepal and staged at Mandala Theatre, Thapagaun, is an example of such a play. The original story was written by Nabin Chauhan, while Anil Subba and Anwesh Thulung Rai adapted and co-directed the play.

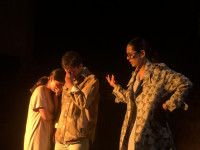

For a play to walk the fine line between riveting entertainment and subtle social depiction, many things need to come together. From the acting prowess of the artists to a creative set design to a captivating sound design, a play needs to encompass all these things to make the audience enjoy themselves while pushing them to reflect as well. ‘Chor ko Swor’ accomplishes this feat due to the sheer passion and hard work of all the theatre artists, creative team, and management team.

The main theme in ‘Chor ko Swor’ revolves around marriage, specifically elopement in Nepal’s Limbu communities. Its namesake refers to a tradition in Limbu communities where relatives of the potential groom visit the potential bride’s parental house to inform them of the elopement and ask for their consent for the marriage.

Bhimhang (played by Prabin Magar) has eloped with Seema (played by Nusa Lingden), and it sets off the start of the play. Bhimhang hails from Chemjong village, while Seema is from Sherma village. These two villages are connected by a shaky yet sturdy bridge, built with wood and bamboo. The relatives of Bhimhang traverse through this bridge to reach Sherma village to fulfil their duty as chor ko swor. As Seema’s family members and elders from the Sherma village reluctantly agree to the union, the marriage ceremony goes underway in all its extravagance.

There’s a saying that makes a round in houses where people reach conventional marriage ages: You don’t marry a person, but you marry their whole family. In this play, however, a person doesn’t marry a family but the entire village. Geographically separated by a gorge, Chemjong and Sherma village have prominent differences even though both are settlements of Limbu communities. In terms of development also, these two villages differ: the boons of electricity and road have reached Chemjong village, while Sherma village still lags behind. While the residents of both villages had planned to build and connect the infrastructures together, in the end, only the Chemjong village flourished as they got electricity poles and roads.

Like the shaky yet sturdy bridge that connects the two villages, marriage between members of the two villages is the bond that strengthens the relationship between the two similar yet different villages and buries residents’ old resentments.

The play's ingenious set design adds to its authenticity and transports the audience through time and space to a rural setting in Nepal in the 2000s. A two-storied house belonging to Seema’s parents stands strong on the left side of the stage, while the bridge that connects the two villages is situated in the centre-back of the stage. The hard work and dedication of Hom BC and Surya KC, the duo who created the set, and the two directors who helped design the set shine bright throughout the play. The second story of Seema’s parental house is completely functional and is used creatively in the story, while the bridge itself is traversed by many people throughout the play. Even a water tap beside the house flows with real water, and a red light under a cauldron dims and glows to closely imitate actual wood fire. The efforts of the makers of the play to go the extra mile to add authenticity wherever possible is what makes this good play great.

But the real beauty of this play lies in the things left unspoken and the things left hidden in plain sight. As the marriage ceremonies start, there is excitement and furore in the air. Pigs are slaughtered, traditional musicians are invited, and homemade alcohol is prepared. Women wash dishes, prepare alcohol, feed the guests, and clean the floors as men relish in the festivities. The marriage ceremony ends as the bride pays respect to the groom by touching his feet, but the groom is restrained by the relatives when he tries to do the same. When a playful teasing between soltis and soltinis takes centre stage, the bride and her sister-in-law converse together on the second floor of the house in the corner with grave faces, inaudible to the audience.

This format of multiple actions occurring simultaneously is followed throughout the play. There are so many things happening concurrently that the audiences can quickly get confused on where to focus. On one side of the stage, there is a budding romance; on the other side, there is heartbreak as a bride leaves her parental house. But the confusion in these scenes adds to the nuances of reality and history. Our lives are often mixed with happy, sad, frustrating, and encouraging moments, and are rarely sequential.

The play is also longer than usual, but its subject matter—the beginning of traditional marriage in a Limbu community till its end–warrants a two-hour running time. The scenes in the play which delve into the human emotions are given time to develop properly. When a sister and brother, who have avoided each other for years after the sister’s wedding, speak again, uncomfortable tension hangs in the air. Like snow and frost that sets in deep as winter progresses, there is a rigid iciness between the two siblings. It takes time for the snow to melt and for old familial relationships to thaw. The play gives ample time for such interactions to properly bloom, which in turn prolongs the play's running time. It’s a small inconvenience to pay for viewing a nuanced showing of family relationships.

The end of the play comes full circle. The play, which started with the elopement of Bhimhang and Seema, ends with the elopement of Sesehang (played by Anil Subba) and Fungma (played by Bedana Rai). Now the residents of Sherma village make their way as chor ko swor to Chemjong village. While the play certainly shows the power imbalance between males and females in domestic life and marriage culture, it restrains from enforcing any suggestions or passing any judgement. It showcases life in the Limbu community’s rural setting in the 2000s in Nepal. Nothing more, nothing less. Sometimes, plays don’t have to make profound statements. Sometimes, plays can just be about weddings.

‘Chor ko Swor’ is being staged at Mandala Theatre, Thapagaun, until June 29.

22.85°C Kathmandu

22.85°C Kathmandu