Theater

‘Territorium’ attempts to break territories of theatre and art

Norwegian artists’ diverse visual performance concert leaves the audience confused, and amazed.

Shashwat Pant

In a dimly lit stage at the Mandala Theatre in Anamnagar, around 50 people sit cross-legged in a circle. After the audience settles down, the spotlight turns to a man playing the Sarangi. After a few minutes of soothing rendition that reverberates around the theatre, a man wearing a black cassock walking towards the centre of the stage steals everyone’s attention. He sings, but in a language unfamiliar to the Nepali audience, but that only escalates the suspense and curiosity.

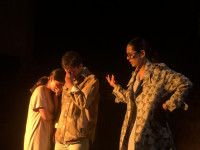

The man playing the Sarangi is Kiran Nepali, a veteran musician who is also a part of Nepali folk band Kutumba. The one in the black cassock is Øystein Elle. And the performance is the part of Norwegian artists Elle and Janne Hoem’s visual concert ‘Territorium’. The artists describe Territorium as a cross-disciplinary performance composed as an intermedial work, that lies at the intersection of a concert, installation, performance and physical theatre.

The performance is equally bewildering and cryptic like the artists’ description, yet it is remarkable. Back at the theatre, it is dark yet soothing, and most of it does not make sense. But the audience remains in absolute calm and quiet as anticipation fills the air.

The stage is set differently than usual. There is a circle in the centre of the stage made out of feathers. More feathers are sprinkled from above the stage that unceremoniously mixes with the ones on the ground. But the way they fall mirrors the movement of sunrays falling through a window. On top of the circle, there is a light, which may be taken as the centre of the universe. Pointing towards the circle are lights that are projected from the ground in three directions—two diagonally and one straight. These lights are all controlled as per the music.

There are two screens behind the stage that projects different visuals while the performers sing and play music. In the visuals, it seems that Elle is trying to manifest himself as different personalities. The pitch of the music corresponds with the character’s expressions. It is almost like sitting in a chamber that portrays someone else’s mind.

These combinations of light, music, movements and props are like witnessing abstract art in motion. Light design and new media artist Jan Hustak deserves special mention for the light-music synchronisation. His improvisation of lighting is commendable as he sets the tone and mood quite brilliantly.

Theatre artist Durga Biswokarma is another delight to watch during the performance—she adds her own flavour to the performances. Her expressions and movement are spot-on. During the act, she seems to be exploring the female body and expressing the stories of boundaries, fear, control and freedom. From dancing as a silhouetted figure to dragging a khadkulo, a large traditional bronze water vessel, her role in the act deserves appreciation. Biswokarma has worked well with scenographer Gunhild Mathea Husvik-Olaussen to mould herself within the periphery of the sound and visual art.

Kiran also adds his elements to the act—the music from his Sarangi is undoubtedly beautiful. While there are hints of traditional Nepali music, Kiran has also improvised a bit with relation to the performers, space and the audience.

.jpg)

Elle says that the musical score of this performance is the result of his quest for sonic treasures, regardless of time and tradition. He collects, composes, and re-assembles textures, timbres, lingual peculiarities, and melodic surplus, which he says, has given birth to a unique blend of traditional and modern. And that keeps the audience glued to the act, as the performance is successful in taking the audience in its journey of high and low, time and again.

The performance seems to be trying to convey many things, without actually saying anything. This can be a double-edged sword—while the scope of understanding can be broad, it can also leave audiences clueless and confused.

But for the Nepali audiences, as well as art performers, it can also send a message that art can come in different shapes and forms. Overall, one could say that Territorium is a breath of fresh air. Sure, productions like these will not do well every day of the week, but time and again, the need to experiment with performance art is important. It can be a way for both the artists and audiences to connect with each other.

The artists are also conducting a workshop to share their art form to 30 Nepali theatre artists. After the three day workshop, a similar show will be conducted at Mandala Theatre on January 7.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu