Theater

Coming full circle

Kathmandu’s newest theatre, Kausi, is housed on the terrace of a family home. Here is how the novel project came to be

Abha Dhital

Regardless of what generation you belong to, pursuing your passion for art is never easy. The career ladder is full of uncertainties; sustaining yourself is always an issue; and the ratio of time, energy and passion you put into your work, to the money you earn never seems justified. This especially holds true for theatres in an age where multiplexes are multiplying and the audience is increasingly inclined towards quick, oftentimes brainless, flicks that can provide them with a break from reality rather than an immersion into it.

Yet, theatres have been persisting against the odds. And every now and then, theatre circuit sees new talents join the circle, if not new theatres rising up from nothing.

On Thursday, Kathmandu’s newest theatre opened its doors to the public. Aptly named Kausi, this black box theatre—a simple, unadorned performance space—by Katha Ghera stands on a rooftop of a four-storeyed house in Teku. And this is not just any other house, for it belongs to Akanchha Karki—an actor, a director, and the co-founder of Katha Ghera. In Bimal Subedi’s, the founder of Theatre Village, words, “She gets to sleep under the blanket of an auditorium every night.”

“Following your passion for theatre is already a radical move, building a theatre in your own home is a different story altogether,” says Akanchha, “When I convinced my parents to help me build a theatre on our kausi, I said ‘please look at it like you are investing on my wedding. I don’t know if I’ll ever marry but when I do, I will keep it low-key, so this my big fat wedding…”

Fast forward a year, and the space is well equipped to accommodate up to 130 theatregoers and has kickstarted stagings with Dayalu Rukh, an adaptation of Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree.

After Sarwanam (1982), this is the first theatre collective in Kathmandu to have its own theatre.

From Katha Ghera to Kausi

Akanchha met her partner in crime, Gunjan Dixit, in school, where Gunjan was a junior. After high school, they ended up going to the same college in Bangalore, India. It was there that they started acting and directing together and discovered their love for theatre, as they pursued Psychology, Theatre, and English.

Once back in Kathmandu, while they did partake in theatre every now then, like ‘rational’ adults, they held on to jobs in their field of speciality, hustling to secure a stable source of income.

“The jobs paid well, yet something felt out of place,” says Akanchha. Having a job meant living a routine life that left them with little time for what they loved. “By the time we got done with our work, it would be dark, and you know what it’s like in Kathmandu...there’s no night life. You can’t work in the evenings, from commute to security and curfew at home—there are all sorts of issues.”

By 2016, the duo had already realised that they needed their own space and more time to practice their craft. Hence Katha Ghera, a self-sustaining theatre collective, was conceived.

“When I quit my job for my passion, it first felt like a mistake. So much was happening around me and the uncertainty hung over my head like a sword,” says Akanchha.

However, the collective soon garnered attention with productions such as Vagina Monologues (three productions till date) and Line, alongside playback theatres conducted at various venues.

As Katha Ghera grew as a collective and with the certainty that this is ‘the work they identified with and were passionate about’, Akanchha and Gunjan realised that they now also needed a space of their own where they could rehearse, conduct workshops, and perform playback theatre. That’s when the idea of Kausi came along.

“We first thought we could use the space as a makeshift, low-cost place to do what we do. But soon we realised that we could bank on this place and make it into an all-purpose theatre. Of course, it needed a lot of money, but we thought ‘why not’,” Akanchha shares.

For Gunjan, Kausi has become her second home, exactly the kind of place she expected it would be. “When you produce a play, the venue is always an issue. The venue determines everything from the running time to the production cost of a play,” she says. “Having a place of our own means we can do so much with the space—we have more liberty to focus on the craft.”

“Kausi is going to be a place for all theatre (as well as art) lovers. We want to accommodate good people and good work,” says Gunjan.

It takes a village

Theatre practitioners are well aware that being involved in theatre comes with its own set of challenges. And hence, the community doesn’t hesitate in coming together to help a budding artist or a new venture, spills Akanchha. Even with a couple of theatres having shut down in Kathmandu in the past couple of years, not one person from the industry discouraged Katha Ghera to open up their own theatre.

“A new theatre is a blessing for all theatre practitioners. We need more of these. People outside the industry might see opening up a new theatre as a financial risk, but everybody in the circuit looks at it as an opportunity,” says Sulakchhyan Bharati, theatre actor/director who is also building his own theatre, Purano Ghar.

If anything at all, the new Kausi does teem with hope and opportunities. When one enters the theatre—with everything from spotlights and stage props to chakatis in the seating area in place—they might fail to acknowledge all the work that has gone into bringing Kausi to life. But if it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a whole theatre community to launch a new theatre.

“This place would not have been possible without so many generous people and their skills and expertise,” says Akanchha. Pointing at lights across the hall, she reveals, “These are expensive lights, and only four of them belong to us at the moment. Other lights were lent to us by our friends from other theatres.”

She also shares that it was theatre practitioner Rajan Khatiwada “who dragged the master theatre builder Suresh Karki” to help build the interiors of Kausi. “Suresh dai and his team built the interiors of almost all theatre houses in Kathmandu from Gurukul and Shilpee to Mandala,” she says, “Whatever you see now is their work of magic. They built this place with so much love and ownership.”

Sudam CK, a theatre actor, has also played an important role in bringing Kausi to life by looking after logistics and stage management, making sure that actors of the opening play were ready to tackle the physical challenge that Dayalu Rukh (The Giving Tree) demanded.

“Ingi (Hopo Koinch Sunuwar) who is a full time technical manager at Mandala, has been a complete blessing as well. Even as he plays the ‘boy’ in this play, he is also dividing his time as the technical manager,” says Akanchha.

The Giving Tree

Akanchha, who is directing Dayalu Rukh says she just knew that the adaptation of the classic Shel Silverstein story had to open Kausi. “This is a universal story and I feel like anybody can connect to it. It still moves me after all these years. This play is particularly special because I had directed it in India, back when we were still students. It was a low-cost but a well-received production that won us awards in multiple festivals. I needed a closure, I guess. I needed to bring that play back home, in a professional setting, to show the kind of work Katha Ghera actually does.”

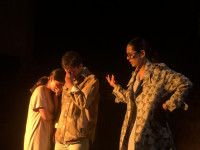

Today the play is being staged with a solid team of eight actors including Ingi, seven of whom—Sumnima Sampang, Roshani Syangbo, Archana Panthi, Prayash Bantawa Rai, Salman Khan Gurung, Alok Thami, Aayan Khadka—play the tree in sync and a talented indie musician Adhishree Dhungana gives the cues as beautifully as she sings. Neither the stage, nor the costumes look thrifty and as an audience, one can actually see the love that has been put in, as a team, into making this play just what it needed to be to open Kausi.

Dayalu Rukh tells the story of a tree that doesn’t hesitate in giving a little boy anything he demands, in anyway it can. And it tells the story of this boy who as he grows into an old man never really stops to think how much of the tree he is asking for and how thanklessly.

“Everyone can relate to it because, at any point in time we are either the tree that’s too selfless, too altruistic, or the boy who’s too selfish to notice all the harm we are causing to a person that loves us,” says Akanchha.

The circuit

Both Kausi and Dayalu Rukh have opened with a sign of promise for the theatre circuit in Kathmandu. It speaks to the talent and passion that the community is full of and how the community comes together as one to support a common dream.

As actor Srijana Subba put it, “Katha Ghera is aptly named for it has been a safe circle for all theatre practitioners who have collaborated with them. And I read somewhere that in a circle we are all equal, there’s no one in front of you, and there’s nobody behind you, no one is above you, no one is below you. The circle is sacred because it is designed to create unity.”

9.51°C Kathmandu

9.51°C Kathmandu