Madhesh Province

People’s courts: How Panchayats continue to shape justice in rural Madhesh

At their best, Panchayats work as excellent community reconciliation mechanisms but they can also be biased, with the influential members exercising most power.

Aarati Ray

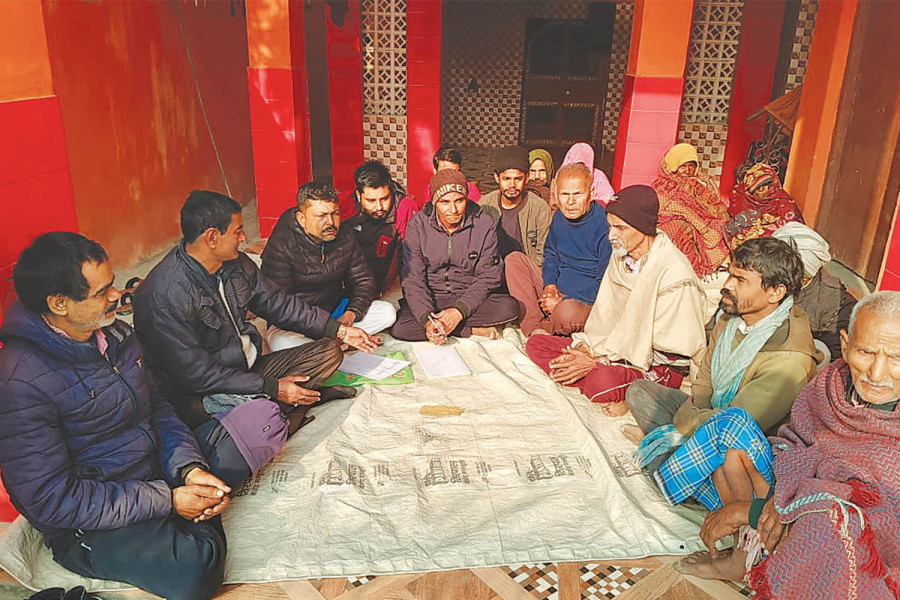

In rural Madhesh, justice isn’t confined to courtrooms or police stations. It’s often delivered through the panchayat—a long-standing tradition of communal resolution, held under the shade of a sprawling tree or in the local panchayat ‘dalan’ (hall). The system, rooted in the social fabric, remains the first resort for conflict resolution.

The panchayat functions in multiple ways in Madhesh, evolving alongside the federal governance structure. At its core, the panchayat operates as a platform where disputes are settled through negotiation and consensus, prioritising mutual understanding and societal harmony over litigation.

In 1962, King Mahendra introduced the ‘Panchayat system’, a four-tier structure rooted in traditional Nepali and Hindu political concepts, extending from the village to the national level.

As explained in ‘Nepal Panchayat Democracy’ by Bharat Dutta Koirala, the term ‘panchayat’ derives from an ancient Nepali system where councils of elders, or ‘pancha’, resolved local disputes through consensus. Though originally meaning a council of five, its membership varied and played a major role in caste and village governance.

Scholars note that panchayats were widespread and effective in governance within caste and village systems across the Indian subcontinent. For instance, the research ‘A Historical Summary of Indian Village Autonomy’ by Mario D Zamora traces the panchayat system back to the Vedic age.

“Although the Panchayat system ended in 1990, ‘village panchayat’ with roots in ancient traditions is active in rural Madhesh in a more evolved form,” says Aarti Kumari Shah, a practicing lawyer and former government attorney of the Dhanusha district court.

Jhumrati Nadaf, a 60-year-old resident of Itharwa in ward 9 of Videha Municipality in Dhanusha, has witnessed this transformation.

“When I was young, villagers would approach elders to resolve disputes, and the decisions carried great authority,” says Nadaf, a former ward chairperson.

The modern panchayat has shifted from rigid authority to a more flexible structure. Villagers organise them voluntarily, and if dissatisfied, they can turn to the police or courts.

Under the federal system, the role of ward chairperson has grown, with them often becoming ‘pancha’, the principal decision-makers in formal panchayats.

Nadaf explains that three types of panchayats exist: village-level, ward-level, and municipality-level.

Village-level panchayat is the most informal type, initiated without ward involvement. In this setup, trusted elders and respected villagers from both sides of a dispute form the decision-making committee (a panel of panchas). The ‘pancha’ panel can have six to ten members. The resolution, often documented on paper, is consensual.

When the village-level decision fails to convince the disputing sides, they approach the ward office where the second type, ward-level panchayat takes place. A formal letter is submitted, and the ward chairperson presides over the proceedings in a dedicated panchayat hall. Here, decisions are recorded on legal documents, ensuring transparency and accountability.

The third is municipality-level panchayat. When ward-level decisions are contested, parties forward the matter to the judicial committee in the municipality office headed by the deputy mayor.

If all these steps fail, disputes are finally taken to the police or courts. The types of issues brought before panchayats are varied.

“Most disputes revolve around land boundaries, water sharing, or minor neighbourhood conflicts,” says Nadaf. “Unlike in towns, these conflicts often involve neighbours or relatives, so people prefer resolving them within the community rather than going to the police.”

For instance, in Karmahi of Videha Municipality’s ward 3, a panchayat convened four months ago to address a matter involving Sumintra Ray’s (name changed for privacy) 21-year-old daughter. Her daughter had eloped with a 25-year-old man from the same village.

Instead of involving the police, the village panchayat mediated the issue, deciding that the couple would marry after both completed their bachelor’s degrees.

“In villages, we rely on the panchayat as it’s a longstanding tradition. It’s cost-effective, keeps matters within the community, and is often quicker than going to the police or court,” said Ray, who is also a sought-out panchayat member in Karmahi.

“For serious issues like domestic violence or major crimes, the panchayat advises villagers to approach the police.”

In the neighbouring Mahottari district, the process is more structured.

“All panchayats involve the ward chairperson here,” says Sashibhusan Jha, the chair of ward 9 of Manra Siswa Municipality. “Depending on the case, fines are sometimes imposed on the wrongdoer.”

Jha notes that land disputes dominate panchayat discussions. The elderly often participate in such panchayats as they are knowledgeable on such transactions.

According to Jha, villagers trust the panchayat system as rural communities are close-knit, unlike towns. “It reflects the community’s belief in unity, elder guidance, and collective problem-solving,” says Jha.

While praising the system’s efficiency, Jha acknowledges its challenges, noting that disputes can arise when parties refuse to accept decisions. “Supporters of the wrongdoer sometimes claim bias, accusing the ward chairperson or panchayat members of partiality,” Jha said. “In such cases, we suggest they approach a municipal panchayat or the police.”

Asi Bharat Thakur, a 44-year-old Police Assistant Inspector in Sahorwa, Mahottari, says, “Panchayats are common here for resolving minor disputes related to land issues, water flow, cattle grazing, or small fights.”

For minor conflicts, the police involve the ward chairperson or panchayat members to negotiate a resolution. If the issue persists or has been handled by multiple panchayats, negotiation is skipped. Serious cases are directly processed through legal channels.

Thakur explains that the villagers have a strong trust in the panchayat system, which helps resolve minor disputes. “If such cases went to court, it would overwhelm an already crowded system,” he says.

Despite the villagers’ reliance on the panchayat, Thakur says they address and register all cases brought to them, regardless of complexity. “Villagers have the right to choose the panchayat over formal legal channels, and the police can only intervene if a case is officially reported.”

However, he does have concerns about the limits of the system. “I only hope that panchayat members refrain from handling serious cases needing urgent legal intervention and remain impartial,” he adds.

Compared to the past, the participation of women in panchayats marks a significant shift in rural Madhesh.

“Previously, women rarely attended panchayats,” Santoshi Mahato of Itharwa who often takes part in panchayats says. “Now they are vocal and demand fair decisions.” Deputy mayors often join panchayat proceedings to address women’s issues, reinforcing their growing prominence in the justice process.

Advocate Shah too sees the panchayat’s role in mediating minor conflicts under the supervision of ward offices and judicial committees as effective, promoting quick justice and community harmony.

Beyond resolving disputes, panchayats serve as a cultural institution, “It’s not just about justice,” says Nadaf. “Panchayats also make decisions on village development and festivals like Chhath, reflecting our shared responsibility.”

Nevertheless, the system is not without its flaws.

Problems arise when panchayats handle cases beyond their scope, such as marital separations, child marriage, and dowry disputes.

According to Shah, there are reports of serious cases, including child marriage and rape, being resolved secretly by panchayats, particularly when perpetrators are influential. This undermines justice and exposes a major flaw in the system.

While villagers trust the panchayat members to solve conflicts, some members exploit their roles, redirecting even minor cases to courts for personal gain.

“At its best, the panchayat serves as a community reconciliation mechanism,” Shah said. “For it to benefit society, villagers must understand their rights and ensure that resolutions align with fairness and legal principles.”

The society’s patriarchal structure too poses a challenge, Mahato says. Despite women leading judicial committees as deputy mayors, their authority is often undermined, with male relatives taking charge. This results in biased panchayat decisions, especially on issues affecting women.

There are also concerns about the informal nature of some panchayats, which leaves room for inconsistencies and disputes over enforcement. Ray says without proper documentation or oversight, decisions can be contested or even ignored.

“To sustain its relevance,” says Shah, “the panchayats must operate transparently, be free from political interference, have equal gender representation, and strictly adhere to local government rules.”

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu