Opinion

How mountaineering has affected the Sherpa community

A new documentary on Kancha Sherpa, the last surviving member of the first summit of Everest, brings focus to the community closest to the mountains.

Jemima Diki Sherpa

For the last half decade, coverage of the spring Everest climbing season has followed several predictable beats: the tragedy of each year’s death tolls, critique of the cutthroat commercial climbing industry, and well-worn retellings of Kancha Sherpa’s story.

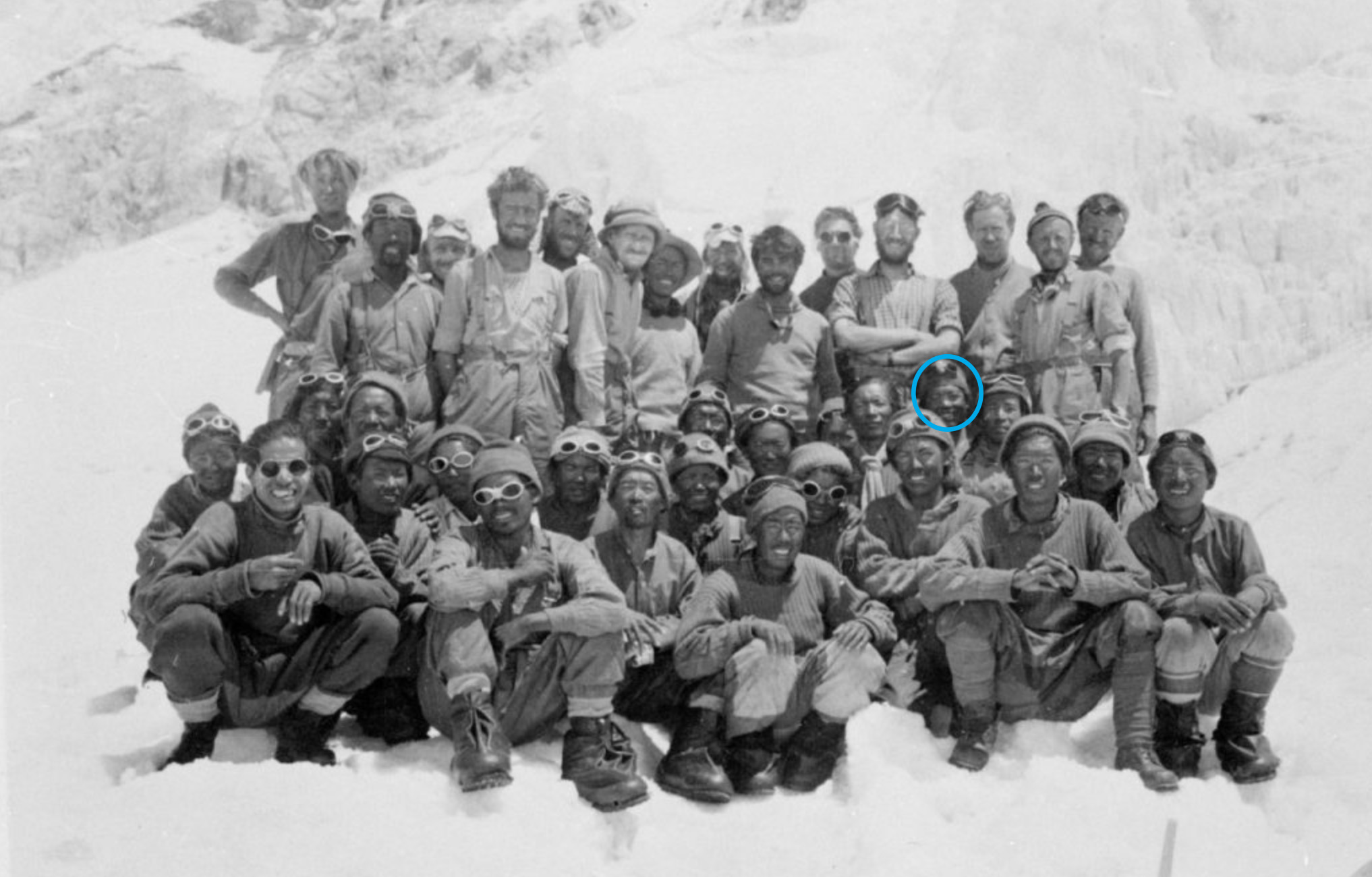

As the youngest and last surviving member of the 1953 expedition, the full glare of the spotlight has fallen on Kancha, now 87, late in life. The tale of the inexperienced 19-year-old who climbed as far as the South Col for eight rupees a day and supported Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary’s historic ascent has taken its place in mountaineering lore. A new feature-length documentary, Kancha Sherpa: Last of the first from the 1953 conquest of Mt Everest covers little fresh ground on the legendary climb but brings new focus to the broader question of how mountaineering has affected Kancha’s family and the Sherpa community.

[Read: This is what it takes to get a foreigner to Everest]

As an impoverished young man, Kancha stopped carrying loads of paper and salt across the Nangpa La pass in arduous, weeks-long trading trips with Tibet in order to seek better fortune in Darjeeling. He travelled with two friends and only some maize flour for his journey, and on arrival, he stayed with Tenzing Norgay, who had climbed with Kancha’s father on a previous attempt on Chomolangma from the Tibet side. This led to Kancha travelling back to Kathmandu with Tenzing to join the ultimately successful British expedition.

These details have often been recorded elsewhere, but one ambitious and sadly all-too-rare filmmaking decision immediately sets this documentary apart: the majority of its considerable length is filmed in the Sherpa language. The movie strategically maintains its connection to Everest history, but its true heart lies far from the slopes of the mountain. Instead, Swedish director Morten Sangpo Borik offers a meditation on the life of a footsoldier of history. In giving Kancha the time and space to speak in his own voice, the piece pulls at threads of culture, faith and family as they all flutter in the winds of massive social and economic change.

[Read: The man who made it possible for hundreds of foreigners to climb Everest is finally retiring]

The film follows Kancha and his late wife Ang Lhakpa (who radiates on screen but has sadly passed since the time of filming) as they travel from their prayer- and ritual-filled home in Namche to chaotic Kathmandu. The capital is home to the couple’s daughter and son-in-law, and their grandson who was born and raised in the city. The film depicts a deeply loving and hardworking family whose three generations are separated by distance and diverging experience, and whose vastly different day-to-day realities are held in a fraying net of cultural connection.

Kancha and Ang Lhakpa speak at length about struggling through years of grinding financial stress in an unforgiving environment. The film neither shies away from nor over-emphasises how little the 1953 expedition changed the family’s dire circumstances. In low, gravelly Sherpa, the couple detail the heartbreak of losing two of their six children and Kancha missing both funerals as he continued to travel, trade, and climb to support the family. It hammers home the rock-and-hard-place nature of the decision multiple generations of Sherpa men have now made in risking climbing: hard toil and frequent deaths on the mountains versus the incessant, body-breaking manual labour and still too frequent death in the high villages. The matter-of-fact way immense hardship and suffering is depicted may be credited to the shared Tibetan Buddhist sensibilities of the filmmaker and his subjects.

In the present day, Kancha’s grandson both mirrors and is sharply disconnected from his grandfather’s experiences. Like Kancha as a young man, his grandson too is burdened with worry about his economic prospects and family responsibility. While his grandfather talks about a hard youth spent collecting firewood, constantly hunting for serviceable footwear, and ending up in detention on an ill-fated trading trip from Calcutta to Tibet, Kathmandu throws up vastly different stressors for young Tshering Wangchu. He talks about disillusionment with job prospects in the trekking and tourism industry, the pollution and disorganisation of the city, and an urban cohort that swirls through the dark corners of substance use and life-threatening depression. Having spent his childhood in boarding schools, he is interviewed in Nepali; he cannot speak Sherpa.

The film does pull no punches in highlighting the stark loss of language, religious faith, and natural environment that accompanied the highly valued material comforts ushered in by the tourism and mountaineering era. “The culture we live in is good, but my fear is that we can’t preserve it in the future,” says Ang Lhakpa, as her grandson expresses somewhat unconvincing intentions to learn and preserve Sherpa language and music.

The film’s English subtitling does not always run true, bearing the telltale signs of second- and third-hand translations; a testament, more than anything, to the gargantuan task of filming, editing, and producing in languages not fully accessible to the crew. With a runtime of 90 minutes, the documentary would have benefitted from a tighter edit. It is lovingly and intimately shot, but extended sequences of B-roll footage—such as lingering on every ingredient being prepped for a family meal, or a series of slowly melting icicles—can wear on a viewer’s patience.

One wonders if and how precisely Kancha Sherpa will find the audience it deserves. Though associated with the seemingly insatiable market for Everest content, it does not feature the high-octane shock-and-awe cinematography, on-the-mountain disaster drama, or large casts with multiple white, English-speaking characters that generally help anchor highly successful documentaries like 1998’s Everest or 2015’s Sherpa for international audiences. Sir Edmund’s son Peter Hillary is featured giving commentary in this documentary but, while insightful, his segments often sit slightly askew to the narrative thread of the rest of the movie. Nonetheless, the film is well worth adding to the collection for mountaineering and Everest history buffs, and it will hopefully reach an audience not often considered: the Sherpa community.

At this point, being Sherpa in the modern world has become inexorably bound with the mountain. Kancha’s grandson Tshering Wangchu says he wants to someday climb Everest because his father and grandfather did it: “Not to show others I can do it, but to prove to myself that I am a Sherpa.” In one beautifully meta device, the family sits in Namche huddled around a laptop watching George Lowe’s 1953 documentary Conquest of Everest, Kancha pointing out when he comes into the frame and speaking over the narrator’s plummy British voice to give frank commentary in Sherpa on the intense fear, pain and exhaustion he experienced during the climb. In another scene, Tshering Wangchu talks about coming to understand his grandfather’s history from reading books about the 1953 summit.

With the rapid cultural, linguistic and geographic shifts in the Sherpa community the Kancha Sherpa documentary depicts, it is likely more and more of us will go digging for our history and sense of identity in the ever-growing detritus of mountaineering media. Thankfully, this film offers something more than just working and dying on the mountain as an example of what being Sherpa means. Instead, it contains an inheritance of quiet, philosophical reflections on long lives fully lived, delivered in the rumbling, murmuring cadence of spoken Sherpa and accompanied by subtitles for those of us who need them.

Jemima Sherpa is a writer based in Kathmandu.

9.51°C Kathmandu

9.51°C Kathmandu