Opinion

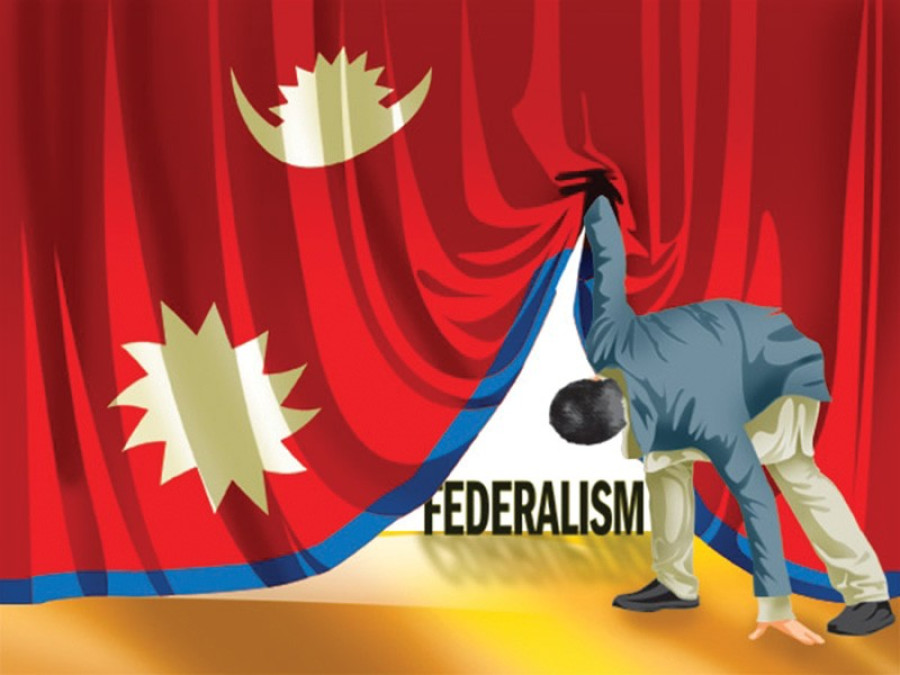

The reluctant federalist

Excessive centralisation of power has become a fait accompli of the present federal Nepal

Krishna Hachhethu

There has always been discontent over the division of federal Nepal’s seven provinces. Following the formation of provincial governments after the 2017 elections, relations between the Centre and Province has gained new prominence in contemporary debates. Ministers, state ministers, secretaries, and the vice-chairman of National Planning Commission, all would be meeting for the first time on 9 December 2018, the date scheduled for the meeting of the Inter-Provincial Council (IPC).

Old habits die hard

The IPC—consisting of the highest level representatives of the federal government (Prime Minister, Home Minister and Finance Minister) and Chief Ministers of provincial governments—is envisaged as a dispute settlement mechanism. There is a wide range of contentious issues that are budgeted for discussion, including establishing institutions like the National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission, which has the responsibility to frame policy and modality of fiscal federalism; laws to regulate centre-province relations in spirit of cooperation, coordination and co-existence; and jurisdiction of provincial government on provincial administration, police and others.

At the outset, despite federal laws preceding provincial laws to form a symmetric structure of federal Nepal, the provincial governments—particularly the Province-2 government, formed by a coalition of two Madhesh-based parties—has preempted through passing the bills related to provincial police and recruitment of provincial personnel on a contract basis.

Though Prachanda, Co-chair of the ruling party, warned that the move could be counterproductive, the provincial initiatives could be justified on two accounts. One is marked by the insensitivity of and undue delay from the central authority to address this problem. The other is that the provisions of provincial police and Provincial Public Service Commissions are among the few of altogether 21 items listed as provincial jurisdiction that don’t overlap with authority of the federal government and concurrent lists.

The Centre has retaliated with the intention to impose central hegemony over the provincial administration. For instance, a draft bill, prepared by the Ministry of Federal Affairs and the General Administration, has outlined a provision that requires the Centre to recruit top officials (chief secretary and secretaries) of provincial ministries. Such a system is practiced in Pakistan, a country infamous for being ‘authoritarian’ and or ‘illiberally federal’. Furthermore, an executive order issued by the Central government limits the power of provincial police down from the sub-inspector level. Besides, the Central District Offices (CDO) are placed as agencies to carry out orders issued by the Home Ministry of the federal government.

It is yet to be seen how the very first meeting of the IPC contributes to settle the problems mentioned above and other issues related to Centre-Province relations in federal Nepal. Generally, ‘coming together’ federal countries (e.g. the United States of America) have a tendency to shift power gradually from state to Centre. In contrast, ‘holding together’ federal countries (e.g. India) have increasingly evolved towards decentralised federalism. Generally, a unitary state transfers to holding together federalism as a response to either of two cases: One, to resist real or potential threats of disintegration from territorially concentrated minority ethnic groups and two, to broaden the scope of inclusive democracy. Nepal does not fit in any one of the above categories. The federal structure of Nepal is designed not in line with holding together federalism since it has nothing to do with managing the ethnic diversity of the country. The case of Madhes could be an exception to some extent.

The factors

The federal Nepal comprising seven provinces largely falls into the category of territorial federalism that could be decentralised (like Germany and Australia) as well as centralised (for instance Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates). But as of now, it is safe to say that the federal system is not working for us as expected.

A number of factors are impeding the process of shaping the present state of Nepal as de jure federal and de facto unitary. One, ideologically speaking, persons in the driver seat are reluctant federalists. PM Oli has claimed on the record that Nepal’s transformation into a federal country was not an outcome of his choice but rather, a product of circumstances.

The Nepali Congress (NC) leaders—and its large numbers of ranks and files—buy this thought. The NC—a party in opposition not only in the Centre but also in all seven provinces—has chosen to remain mum on Centre-Province tensions as if the issue does not deserve to gain the attention of the opposition party. Only the members of the provincial legislature and executive, who are essentially the new stakeholders of the seven-province federal Nepal—are begging for authority to equip themselves to carry out their minimum functions.

Second, constitutionally, it is framed through centralised federalism that there are hardly few out of 21 items listed in provincial power that don’t overlap with the list of central jurisdiction and joint authority. Nepali federal design is proudly portrayed as cooperative federalism. Its literate meaning, both in Nepali (sahayogi) and English, sounds sweet. But in federal terminology, it conveys a different meaning: a process ensured by provision of joint authority on which the Centre enjoys overriding power over provinces.

Third, the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) is in power not only at the national level but also in six-out of seven provinces and majority of local governments. Nepal, as it stands, fits to the past story of India and the present case of Ethiopia (its radical ethnic federalism is overshadowed by de facto one party system) due to prevalence of a one party dominated regime.

Furthermore, the present ruling party of Nepal, CPN is a hierarchical, highly centralised, and personality-based party. It claims to follow the principle of democratic centralism—a system that espouses on power concentration. Given that, federalism—as a system built on division, distribution, sharing and proliferation of power becomes the anti-thesis of democratic centralism Things may be slightly different had the NC been a ruling party in any one of seven provinces and or even if a member of dissident faction of the NCPheld top position at the provincial government. But this is merely wishful thinking. Those in helm of power at provincial level are overridden by their position in hierarchy of their respective party organisation. From appointing Chief Ministers to taking important policy decisions—most actions are taken by involving only a coterie of people often ignoring wider deliberation. Regrettably, contrary to popular belief, excessive centralisation of power has become a fait accompli of the present federal Nepal.

Hachhethu is a professor of Political Science and the author of Party Building in Nepal.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu