Opinion

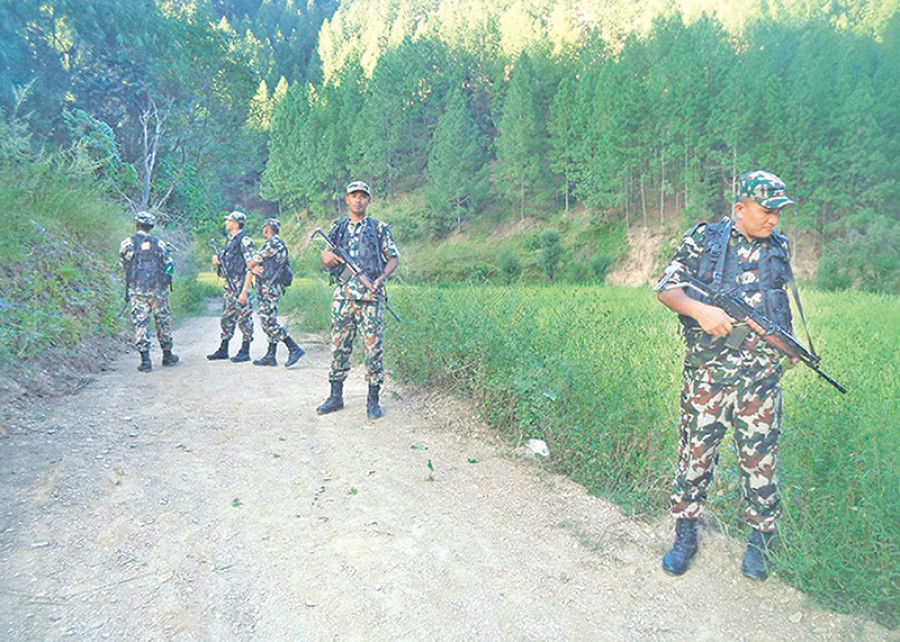

Men in green

Conservation actors have overlooked the army’s excesses in protected areas

Shradha Ghale

Protected areas in Nepal are militarised zones where governance largely means law enforcement. At present a total of 7,627 army personnel are deployed in 138 outposts in 10 national parks, 3 conservation areas and 6 protected forests. The army receives a large chunk of the national park budget. There are 33 guard posts in Bardiya alone, and 21 in Banke. Game scouts and/or army personnel regularly patrol national parks and punish people for the slightest infringement of rules.

Green violence

Article 24 (2) of the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act gives “the authorized officer” the right to open fire at anyone suspected of committing a wildlife offence, “and if the offender or the accomplice dies as a result of such firing, it shall not be deemed an offence.” Such a provision violates the right to life guaranteed by the Constitution.

For instance, in a well-known incident of March 2010, three Dalit women including a minor were shot dead by army personnel in Bardiya National Park. Investigation by human rights organisations revealed that the victims were local women who had entered the park to collect the bark of kaulo trees. Some reports claimed they had been raped before being murdered. Despite demands for justice from various quarters, the Nepal Army’s court of inquiry dubbed the victims “poachers” and let the perpetrators go scot-free.

A recent study in Chitwan National Park revealed that even after Nepal became a federal democratic republic, the locals have faced various forms of violence committed by the army—beating, arbitrary arrests, torture and sexual assault. Most victims belong to poor and marginalised groups. A Chitwan-based NGO named Prabhat Kiran Sewa Samaj has documented 116 cases in which army personnel have raped or “married” local women and then disappeared at the end of their two-year posting, leaving the women to face social stigma and raise children born out of wedlock. Most of these women are Janajatis and Dalits. None of the army personnel have been convicted.

In Banke and Bardiya, locals in the buffer zone said armed guards often resort to beating, verbal abuse, confiscation of hasiya and fishing equipment, arbitrary arrests and fines. Locals found to be collecting thatch or fishing without permits are sometimes forced to do chores for the army—cutting grass at the army post, cleaning up, painting the walls at the barracks, etc. A number of people said they were punished for having eaten the meat of a dead animal found in the forest. Catching fish for an evening meal or collecting dead wood from the forest amounts to a crime.

Allies of conservation actors

Despite well-documented cases of human rights abuses by the army and the high cost of militarisation, conservation organisations in Nepal have long advocated for the militarisation of national parks. Those who lead the conservation sector consider the Nepal Army an important ally in their agenda of wildlife protection. In the words of a senior official at WWF, “National parks in the Tarai still exist because the army has guarded them. People consumed by everyday worries are not capable of creating or sustaining such a grand, long-term vision [of national parks]. It is naïve to question the presence of the army.”

The army is regularly felicitated for its role in curbing wildlife crime. It was one of the key institutions recognised for making 2015 “a zero poaching year”. In 2014, two battalions and one company of the Nepal Army were honoured with the “WWF Leaders for a Living Planet” award. While celebrating the army’s contribution, conservation actors tend to overlook the excesses committed by army personnel.

An incident that took place near Chitwan National Park on 12 May 2012 is a case in point. On that day Mati Mahato (name changed), a landless woman and a mother of two, was cutting grass in the Beslar buffer zone community forest when a Nepal Army soldier patrolling the park tried to rape her, and when she resisted, violently beat her. Mahato, the sole breadwinner of her family, suffered serious injury and psychological trauma. The soldier, Chitra Bahadur Pradhan, belonged to Nandabaks Battalion. A few months later, in September 2012, Nandabaks Battalion received a conservation award from WWF for its role in curbing rhino poaching. No mention was made of Mati Mahato’s case even though the incident had been widely covered by the media, including by large mainstream outlets such as Kantipur daily.

Continued militarisation

A few years ago the government decided to deploy the army in Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, which falls in the ancestral territory of the Magar, and in Makalu Barun National Park, which lies in a region primarily inhabited by Janajati communities such as the Rai, Sherpa and Shingsawa. The locals of these areas, many of whom knew about the army’s excesses in other national parks, fiercely protested against the government’s decision. The community leaders tried to invoke international instruments such as International Labour Organisation (ILO) 169 to protect their rights, but to no avail. In 2015 the government mobilised the army in both these protected areas.

Despite the problems resulting from militarisation and heavy-handed regulations, conservation organisations lay overriding emphasis on surveillance and law enforcement in national parks. A 2016 project agreement signed between the National Trust for Nature Conservation and the Zoological Society of London-Nepal is a typical example. The focus of the three-year transboundary tiger project is to make the security network more effective, set up new security posts and support security forces and community youth in patrolling the protected areas.

Conservation organisations have formed “community-based anti-poaching units” to protect animals such as tigers and rhinos. But critics say such efforts are aimed not at democratising park governance but at mobilising local actors to implement the coercive conservation measures of the state.

A metaphor for the state

As the instances above show (and there are plenty more), army personnel deployed in protected areas have not limited themselves to guarding forests and wildlife. While military outposts and surveillance technology have been expanded to an increasing number of forests, there have been hardly any efforts to ensure that the armed guards are sensitive towards the local population or held accountable for excesses. Not a single member of the army responsible for crimes against local women and men in national parks has been brought to justice.

In a recent piece, journalist Subina Shrestha wrote that for people who live around Rara National Park, the park is a “cruel metaphor for the state.” This is true for the majority of national parks and reserves in Nepal. The ruling elite continue to mobilise armed men to evict, subdue and punish historically marginalised populations in these resource-rich lands.

Ghale, a former op-ed editor at the Kathmandu Post, is a freelance writer

13.03°C Kathmandu

13.03°C Kathmandu