Opinion

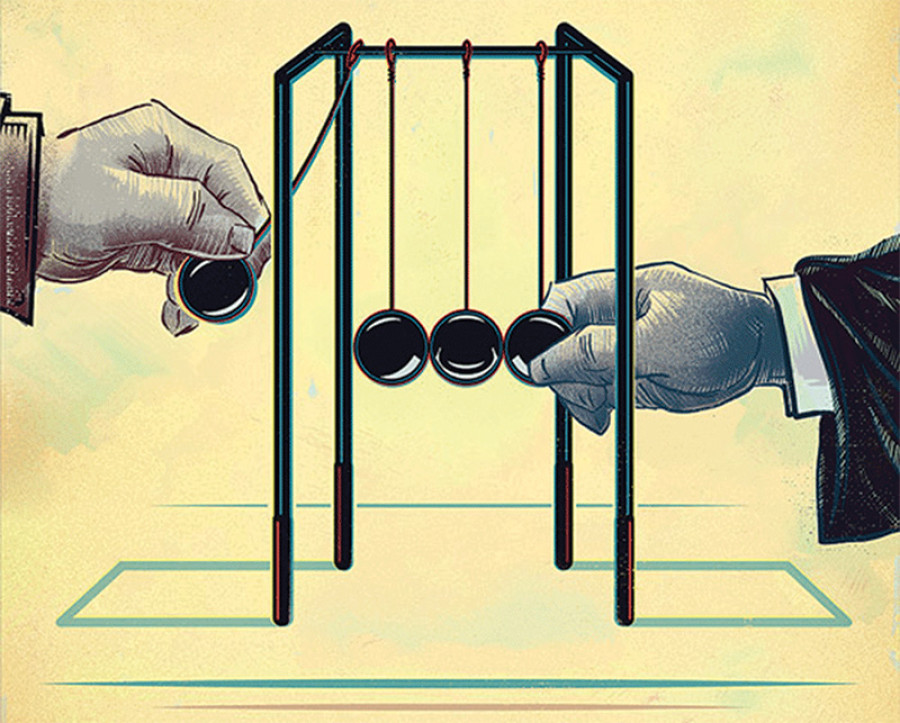

Press reset

PM Oli’s Delhi visit marks the beginning of a new phase of Nepal-India ties in the shadow of China

Amish Raj Mulmi

The bluster has gone from both sides, and there is a new softened approach on the two neighbours’ part. For the first time in many years, the narrative around a Nepali prime minister’s visit to India is shaped around the Indian response, rather than what the Nepali prime minister is expected to bring to the table. Much of it is because of the decisive electoral mandate KP Oli won, and the more measured approach New Delhi has taken towards Kathmandu since his electoral victory.

The Nepal-India relationship is at a critical juncture. The Indian position in Nepal has been weakened post the 2015 blockade, and Delhi has few allies it can trust in Kathmandu today. Oli’s electoral victory showed India’s word can be ‘defied’ and be ‘politically attractive’ at the same time: ‘Delhi tried to block his electoral alliance with the Maoists; it tried to block their election victory; and it tried to stop the announcement of the merger of the two communist parties. It failed on all ends.’

Since then, Delhi has backed down. The Indian establishment has maintained it respects Oli’s electoral mandate, and the visit by Indian External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj signalled it would work closely with his government. There is a conscious pullback of Indian micro-management in Nepali politics, and sources suggest Oli has also assured India he will not work against their interests. Statements to the press in Nepal leading up to the visit point towards Oli’s focus on the economic agenda than the political.

In many ways, this visit marks a ‘reset’ of the Indian view on Nepal. There is the matter of the Nepal-India treaty, which the Eminent Persons’ Group (EPG) is currently preparing a final report for, and those aware of developments say the EPG will recommend a new treaty. Sources say India has consciously decided to stay away from the internal political management and government building exercises while focusing on infrastructure and development projects in Nepal. Delhi will work closely with the regime in power, and the Indian view will be confined to a set of its security interests in Nepal, as an analyst said. Any move against Oli at this time will also be viewed in Nepal as undermining the democratic verdict and hence antithetical to Indian interests.

The counter-view among the security agencies in the Indian establishment is that appeasing Oli may backfire as he grows closer to China. Proponents of this view believe in engaging with Oli, but argue against giving him preferential treatment or bending over backwards to accommodate him.

In both these instances, however, there is the looming presence of China.

Commonalities and convergence

In recent months, there has been a strategic recalibration of Indian foreign policy vis-à-vis China. The new foreign secretary visited Beijing earlier this year, while a cabinet advisory asked ministers to stay away from Tibet-related events to accommodate Chinese concerns. India is said to have told China it would not intervene in the Maldives, and a government official was quoted as saying, ‘The days when India believed that South Asia was its primary sphere of influence and that it could prevent other powers, such as China, from expanding its own clout are long gone...We can’t stop what the Chinese are doing, whether in the Maldives or in Nepal, but we can tell them about our sensitivities, our lines of legitimacy. If they cross it, the violation of this strategic trust will be upon Beijing’. This admission aligns with the new viewpoint that India will engage with China on ‘commonalities’ rather than focus on the differences. “We will deepen the areas of convergence (with China). But we will continue to hold on to our core interests and positions,” an unnamed government official told Hindustan Times.

The shift in the Indian position vis-à-vis Nepal is not unique to the latter, an analyst argues, and India’s willingness to work with Oli comes from both Nepal-specific concerns as well as these larger geopolitical realignments in recent years. The reset has begun, says Professor SD Muni, former Indian special envoy and ambassador, and both sides have softened their stance.

The larger question, he argues, is whether the change in stance is ‘cosmetic, or strategic’. If Oli reverts to his ultra-nationalism and denounces India, or if India’s

arrogance and intrusiveness in Nepali politics continues, not much will improve, he says.

Similarly, a lot will depend on what India can offer Oli during this visit, says Sanjay Kapoor, editor of Hard News magazine. ‘The greater burden is on the government of India to ensure relations are normalised,’ he says. Indian infrastructure projects in Nepal have long been delayed, and as Chinese investment increases in the country, there is a growing realisation that India cannot compete ‘dollar-to-dollar’ in terms of investments with China. ‘We have to acknowledge that at this point, the capacity of the Chinese to build those projects is far greater than our capacity, both financially and technically,’ Indian Foreign Secretary Gokhale told the Parliamentary Standing Committee on External Affairs last month.

New order

There is also a case to be made for how Indian foreign policy has evolved in recent years. Gone is the earlier stance of having a ‘grand strategy’ encompassing its foreign policy. Instead, Gokhale told the Committee, ‘My own sense is that we are still at the beginning of what is going to be the shape of things to come…having a grand strategy when the world is in such flux, might land the Ministry of External Affairs with the pitfalls that the Standing Committee might then question us as to why we thought something was going to happen and did not.’ Gokhale pointed out that the world was moving back into an age where two powers—US and China—have ‘put forward ideological positions about what [their] Foreign Policy consists of’, and that India ‘should and do have our own worldview’.

One point analysts agree upon is that India-Nepal ties in the coming days will depend on how Nepal engages with China. The geography cannot change, as Kapoor argues, and the socio-cultural linkages between India and Nepal remain. Yet, one cannot ‘unhinge investment from politics’. Chinese investments in Nepal remain a concern for Delhi, but not overtly so, especially in light of the foreign secretary’s comments that Indian investments in the neighbourhood are ‘demand-driven’, where India ‘wait[s] for the governments of our neighbours to tell us what projects are required’.

Building trust

What India is concerned about is whether Nepal keeps its security interests in mind. ‘Any project that hurts India’s strategic sensitivity’ will be a red line for New Delhi, says Muni. Oli is said to have assured Delhi that he will have a consideration for Indian interests, and sources suggest multiple conversations have occurred between him and Delhi post the elections. Delhi seems to have taken a wait-and-see approach that is based on seeing how the relationship plays out, rather than being unnecessarily paranoid about the Oli government and its intentions.

Then there’s the fact that China has cashed in on India’s alienation of its neighbours, something that is apparent in Delhi circles. Much print space has already been dedicated towards castigating Indian foreign policy in recent years. The Modi government is also in no mood for any major foreign policy hiccups in the run-up to next year’s elections, the analyst said, and will try to stay away from any flare-ups until 2019.

Oli also visits Delhi with a political mandate unlike that of any Nepali PM before. While previous prime ministers felt beholden to Delhi in some way or the other, the Oli of 2018 has no such compulsions. There’s also the matter of the revision of the 1950 Treaty. The consensus among Nepali political parties seems to be that it is now obsolete. Sources say a new treaty between the two countries will be signed during Oli’s prime-ministership, if not during this visit.

This visit will need to be seen against these multiple backdrops. The insinuation that a section of the Indian establishment is considering an anti-Oli narrative or a return of monarchy is ‘plain noise’, said the analyst, and is to be discarded. Of course, if India reverts to its micro-management in Kathmandu, Oli will use it to his advantage, but for now, Delhi is willing to engage with him on equal terms. The Oli visit, therefore, is correctly a ‘reset’ in Nepal-India relationships.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu