Opinion

Clear vision

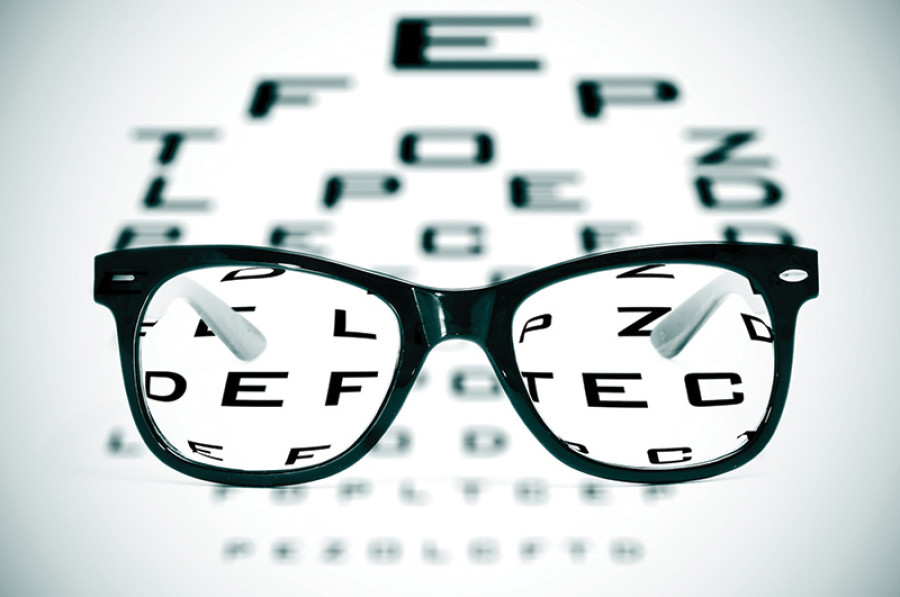

Further homework is required before launching a new optometry course in Nepal

Birendra Mahat, Dinesh Kaphle & Himal Kandel

Eye care services in Nepal were rudimentary before 1980, with three ophthalmologists and 16 hospital beds available for the whole country. After the Nepal Blindness Survey (NBS) in 1981, there has been a paradigm shift in eye care services. The eye care services are more NGO-led rather than government-led. The global initiative of “Vision 2020: The Right to Sight” launched in February 1999 by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) has provided guidelines, targets and strategies to eliminate avoidable blindness. Thus, the production and distribution of the eye care professionals has been of the utmost importance since then. This has been possible through collaborative work of teaching hospitals, eye hospitals and respective regulating bodies like councils.

The major human resources in the eye care services in Nepal include ophthalmologists, optometrists, ophthalmic assistants, optical dispensers and eye-health workers. The regulating body for optometrists is the Nepal Health Professional Council (NHPC). Till date, there is no independent council of optometrists.

About optometry

Optometrists are healthcare professionals who provide primary vision care, ranging from sight testing and correction to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of vision changes. They are licensed practitioners, who primarily perform eye exams and vision tests, prescribe and dispense corrective lenses, detect eye abnormalities, prescribe medications for certain eye diseases and refer some eye conditions if required.

The four-year degree course, in general and as per the World Council of Optometry (WCO), follows criteria similar criteria in academics and internship training. However, the USA, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, most European countries and a few Asian ones run extensive five-year Doctor of Optometry (OD) course. Both Doctor of Optometry and Bachelor of Optometry have been recognised as graduate degrees in optometry. Graduate optometrists are entitled with the prefix of doctor in Nepal and abroad. The new institutions that emerge in the future for the production of optometrists should follow the rules and regulation and education standard as recommended by Nepal Health Professional Council.

Current Scenario

In the last two decades, 86 optometrists have graduated from an optometry institute of the country—Institute of Medicine. And nearly half of them have emigrated for several reasons. There are two major reasons behind this high rate of emigration: First, high competency in the entrance examination (which now caters to 10 students a batch) and second, lack of a retention policy aimed at graduated optometrists. Each year, around 100-150 Nepalis go to neighbouring countries, largely India, to study optometry.

The current population of Nepal is about 30 million. The number of optometrists as registered in NHPC till date is about 400. Hence, with empirical data on the number of optometrists (~350) staying in the country, there is one optometrist serving about 85,000 people. The WHO recommended human resources ratio for optometrists by 2020 is 1:50,000. Thus, with this estimation, the required number is likely to be achieved in the next five years.

With this background, a big question was raised among Nepali optometrists: Is the National Academy of Medical Science (NAMS) prepared for the required infrastructure (vision science laboratories, equipment) and lecturers to teach optometry to 40 students in five eye hospitals per year in Nepal? A survey was conducted among optometrists so as to understand their views and concerns regarding the newly launched Optometry programme at NAMS.

Around 58 percent of the respondents suggested that the current optometry program should go ahead with a revised curriculum and vision science laboratories should be set up. More than half of the respondents thought that the current curriculum is inadequate—particularly in basic science, pharmacology, and other specialised optometry areas such as paediatric optometry, ophthalmic optics. More than two-thirds (67 percent) of the respondents thought that the NAMS does not have adequate infrastructure, particularly for vision science and optical laboratories and equipment to start the program. Nearly half of the respondents thought that teaching students at five different hospitals is likely to lead to inconsistent competency among graduates. About two-thirds of the participants expressed concerns about quality assurance in the new optometry programme. Nearly half of the participants were concerned regarding the human resources, particularly lecturers available for running the optometry programme. To maintain the quality and consistency in teaching, many suggested centralised teaching, rather than teaching in individual hospitals, prior to sending the students for clinical placements.

Short-sighted

The programme lacks proper ground work and intense collaboration, which may result in a disastrous situation for optometric field in Nepal. This poor planning starts right from the intake criteria wherein there is unequal and biased opportunity in the entrance examination for 10+2 (science) students and ophthalmic assistants. It seems NAMS has a myopic understanding of optometry, its scope and nature of practice. With no full-fledged futuristic modality in academic and clinical practicum in terms of human resources and lab equipment, the future optometrists may be less competitive—thereby not meeting the basic standards required in optometry practise. This ad hoc approach of limited stakeholders seems to help out the hospitals and also seems to provide temporary benefits by utilising human resources at a low cost. But, we need to think beyond 2020 and the longer-term effects of adding programmes that lack the necessary resources and preparation. The newly launched programme, Bachelor in Optometry and Vision Sciences, is most likely to suffer. This verifies the lack of concern on the part of the concerned authorities to understand the basic national and international norms that regulate the optometry profession.

The optometry programme, if run with the motive of improving and upgrading optometry to match the needs of the nation, would definitely hit a milestone in eye-care delivery. Such an academic institution must have a robust faculty and state-of-art labs to teach optometry. But the plan NAMS has proposed to teach students at different hospital settings leads towards variation in the teaching-learning modality and leads to a disparity in the standard of the graduates. These issues produce incompetent optometrists, rather than skilled and independent practitioners. Moreover, this new optometry programme is based on an outdated mode of learning, inculcating more or less same curriculum of IOM, which was developed 20 years ago. Therefore, the programme needs urgent revision and consultation with the corresponding authorities at the earliest, lest it create problems in eye-care services.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu