Opinion

Conditioned happiness

Nepal is influenced to a great extent by festivals, and the economy is particularly dependent on the advent of these occasions.

Achyut Wagle

Nepal is influenced to a great extent by festivals, and the economy is particularly dependent on the advent of these occasions.

Although there is no systematic research, according to a rough estimate based on the import figures, about 65 percent of the annual sales of household durables, 40 percent of the sales of property, vehicles and precious metals, and almost 50 percent of the sales of consumables take place during the Dashain-Tihar-Chhat season.

Airlines and bus companies eagerly wait to exploit the festival-generated movement of Nepali travellers.

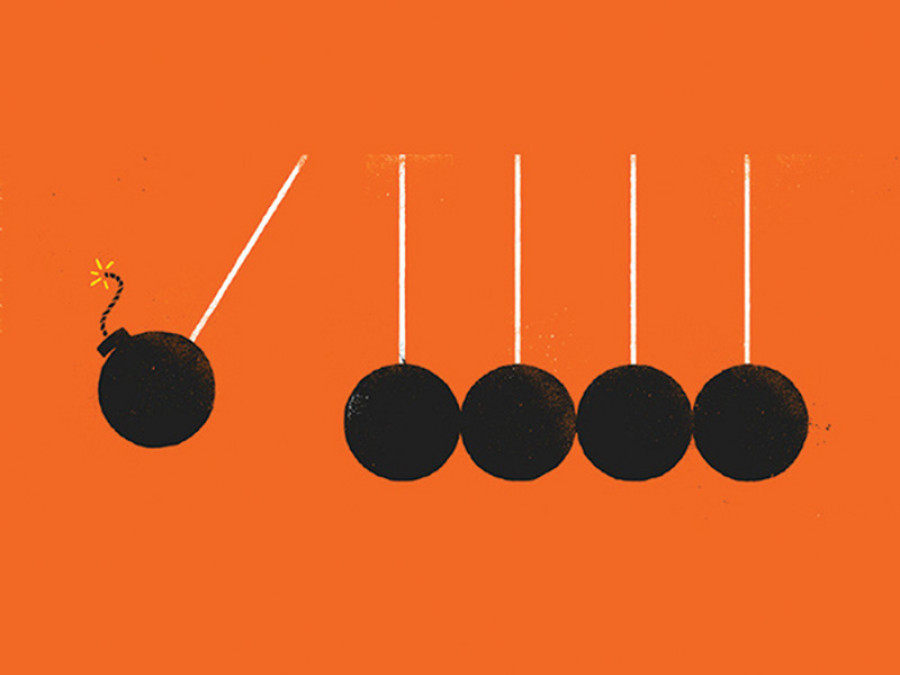

The single thing that has ruined the entire festive mood and subsequent economic activities is the utter deficit of physical infrastructure.

For all practical purposes, festivities are conditional on things like whether the Mugling-Narayanghat stretch of the road is functional, and whether bus or air tickets are easily available.

The price fairness is another major concern, particularly for international travellers. For example, airfare for flights between the Kathmandu-Delhi sector increase up to six times during this season every year.

The business community has its own sad story to tell. Due to limited or inefficient movement of surface cargo vehicles, goods barely reach the market to cater to pre-festive demands.

Demurrages and unpredictable delays that add substantial costs make products uncompetitive. Many businessmen, therefore, place limited orders or don’t risk even that. It is also peculiar that almost 80 percent of this festival economy is Kathmandu-centric and more than 95 percent of the goods are imported.

Except for a little market share of meat and agro products, all supplies ranging from vermilion powder to vehicles depend on imports from India, and to some extent China.

The mismatch

This demand and supply mismatch of the festival-centric Nepali economy provides a credible cue to peep into its actual problems and prospects.

The proverbial chicken-and-egg story could always be repeated when pondering whether the infrastructure preceded the economic growth, or vice-versa.

But in Nepal’s case, our growth prospects in terms of economic, social and human development have been historically constrained by the lack of basic, adequate infrastructures—energy and physical connectivity in particular.

In the energy sector, we are perhaps over-glorifying some of the bureaucrats and ministers for reducing power outage hours, which in fact is a mere stopgap arrangement, relying on import of about 400MW of power, yet again, from India.

However, developments in this sector are rather hopeful. But the state of physical infrastructure and connectivity is still pathetic, to say the least.

Nepal’s all-weather road density of 0.9km per thousand population is

among the lowest in the world.

The functionality of the road is another frustrating phenomena, thanks to decades of underinvestment in transport and connectivity.

Nepal’s only international airport has become unmanageably congested. One hour waits for aircrafts, both to take off and land, is now the new-norm in the airport schedule due to heavy air traffic.

No doubt, private investment in Nepal’s aviation service has been impressive, but the country’s infrastructure deficit is poised to pull their profit bar down through no fault of their own.

Future concerns

The worst, perhaps, is not the bottleneck that we are facing today, but the utter lack of hope in a scenario for the future.

We have no credible plans to develop any form of mass public transport infrastructure. The proposed 78km Kathmandu-Tarai fast-track road is a stark example of our inefficiency in public sector development.

By any economic standards, be they in terms of investment, management or development, the construction of a 78km long road should be a trivial matter for a national economy.

But for the last eight years, the fast-track project has become the victim of what can be called the politicisation of development.

Similar are the plights of the Nijgadh, Pokhara and Bhairahawa airport projects. Even assuming that these projects are completed, say, in the coming seven to 10 years, the connectivity crisis in the interim is sure to take a huge toll on the economy and public life.

The political indifference is evident in the hardships that people are repeatedly exposed to.

Even less costly measures like adding a short domestic runway in Kathmandu airport or exploring the option of water transportation, for example, in the Narayani river between Mugling and Narayanghat, would have greatly ameliorated these difficulties. But no one seems to care.

The festival season’s shopping and travel ticket booking exposed that, in addition to the physical infrastructure, Nepal’s digital infrastructure is equally weak and unusable.

The use of physical cash for the purchase of merchandise and long queues of people at the ticket counters for long-distance buses belied the government data that claims 48.4 percent Nepalis now have access to the internet.

It shows that the gap between digital literacy and the ability to use it productively is still very high.

Our failure to use information technology to facilitate the payment system, among other equally important aspects of e-governance, is already a serious cause for Nepal’s development concerns.

Handicaps relived

For long Nepal lamented the lack of investible funds for infrastructure development.

But what is evident now is that it is not the funds that are impeding our development process now, it is the management shortfall.

Nepal now stands in a position to finance a reasonable number of medium-sized capital-intensive projects.

Their successful implementation would have helped to attract private and foreign investments. But, we have failed miserably to demonstrate our project management abilities.

The fast-track, the Kathmandu ring-road and the Mungling-Narayanghat road expansion projects all expose these vulnerabilities.

No doubt, Nepal needs foreign direct investment (FDI) in large infrastructure projects. But, Nepal’s investment concepts hinge between a so called nationalism-driven passion and the harsh reality of our trust deficit in attracting FDI.

Hastily concluded deals like the Upper Karnali Hydropower Project with the GMR group of India and Budhigandaki Hydroelectric Project with the Gezhouba Group of China are not only proving costly for the country but are also sending wrong signals to potential investors as well.

It was apparently clear three years ago that GMR was unable to generate required finances in the present equity structure of the company.

But it continued to get the timeline extended for financial closure. The track record of Gezhouba shows that it simply has the intention of occupying the project rather than actually developing it.

We have so far failed to attract substantial foreign investments for large infrastructure projects other than hydropower development.

The next Dashain can be happier only with improved infrastructure, connectivity and mobility. Anyway, Happy Dashain!

- Wagle, a founding editor of the economic daily Arthik Abhiyan, is an eco-political analyst

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu