Politics

Court nod to Oli’s appointments leaves executive unchecked

Endorsement of the disputed appointments made without hearings has weakened constitutional checks, experts say.

Binod Ghimire

The constitutional bench of the Supreme Court, which had divided opinions on the legality of appointments to constitutional commissions, remained similarly split on then KP Sharma Oli government’s decision to revise the Constitutional Council Act through an ordinance.

After sitting on 15 writ petitions for almost five years, the top court on Wednesday upheld the decision of the Oli-led Constitutional Council to recommend chiefs and members of 11 constitutional commissions, as well as then President Bidya Devi Bhandari’s decision to appoint them without parliamentary hearings.

With then Speaker Agni Prasad Sapkota and leader of the main opposition Sher Bahadur Deuba refusing to show up in the council’s meeting, the Oli administration made a controversial amendment to the Constitutional Council (functions, duties, and procedures) Act, allowing three of the six-member council to nominate candidates for appointment to constitutional commissions.

The council, on December 15, 2020, recommended 38 candidates for various commissions. Of them, 32 were appointed on February 3 of the following year. Likewise, 20 others recommended on May 4, 2o21, were appointed on June 24 that year.

The May 4 recommendations came just before then Prime Minister Oli dissolved the House of Representatives.

The appointments were made citing a provision in the parliamentary regulations which says appointments would not be obstructed if a parliamentary hearing cannot be held within 45 days of the recommendation.

Fifteen different petitions were filed challenging the ordinance, recommendations, and the appointments.

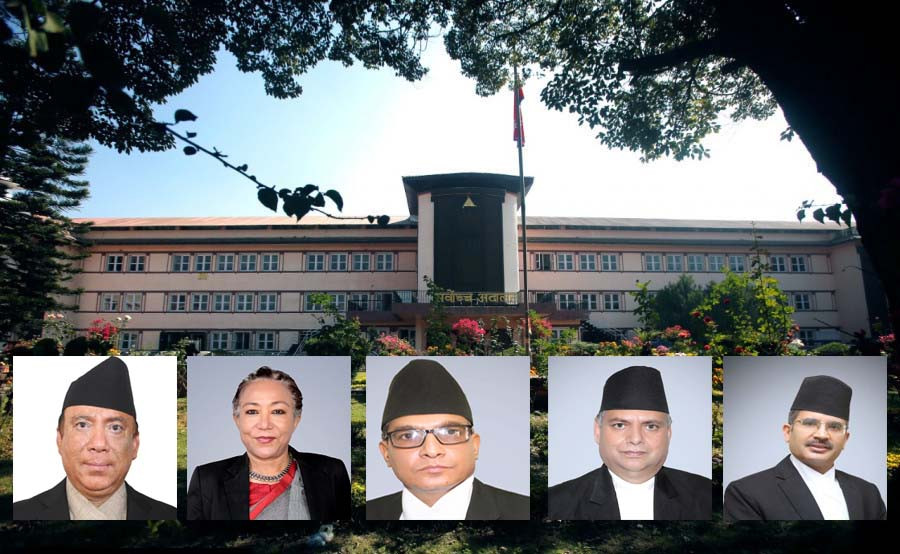

Passing the verdict on Wednesday mid-night, three—Sapana Pradhan Malla, Manoj Kumar Sharma and Kumar Chudal—of the five-member bench upheld the appointments scrapping the writ petitions against the revision in the Act, recommendations of the office bearers and their subsequent appointments.

Chief Justice Prakash Man Singh Raut and justice Nahakul Subedi, however, found that the recommendations and the appointments from December 2020 and February 2021, respectively, were unlawful, and called for their scrapping.

Raut and Subedi said the recommendations of 38 were made without following a mandatory provision in the Act which says all the council’s members need to be informed about the meeting 48 hours in advance. Then Speaker Sapkota had challenged the recommendations of 38 saying it was done without informing him about the meeting.

Raut and Subedi, however, agreed with the other three justices in upholding the appointments of 20 others, noting that, unlike in the case of the 38, Sapkota had not claimed he was deprived of timely information about the meeting.

Justices Sharma and Chudal have explicitly said the executive holds the authority to issue ordinances at its discretion. Others were silent on the Oli government’s move to issue the ordinance. However, by upholding the appointments made based on the ordinance, they effectively aligned with Sharma and Chudal, according to constitutional experts.

“The whole bench has upheld the ordinance,” said senior advocate Dinesh Tripathi, one of the petitioners. “The Constitution’s Article 114 (related to ordinance) is for exceptional situations. There was no emergency for the Oli government to issue the ordinance. By upholding the decision to issue the ordinance, the court has left the executive unbridled. It has defeated the entire purpose of constitution and constitutionalism.”

He said the bench has essentially established that parliamentary hearing is not mandatory. Upholding the appointments made on the basis of parliamentary regulations and totally ignoring the constitutional provision of parliamentary hearing means regulation can supersede the constitutional provision, according to Tripathi. Except for Malla, who has issued an order for holding parliamentary hearings of the appointees, others have not deemed it necessary.

Experts say it is hard to believe that the constitutional bench did not test the constitutionality of the ordinance, which they believe contradicts the spirit of the constitution. “The bench has failed to carry out its responsibility,” said Bipin Adhikari, professor at Kathmandu University School of Law.

According to Article 137, the role of the bench is invoked when a case requires serious constitutional interpretation. However, the Raut-led bench delivered the verdict as if it were an administrative court, without addressing the core constitutional issues, according to experts.

“The key question the court was supposed to address was whether issuing an ordinance falls within the limited authority of the executive, but it completely failed to do so,” said senior advocate Raju Prasad Chapagain.

The petitioners had demanded answers as to what is the prerequisite for issuing an ordinance? Can an ordinance amend or replace an existing Act (law) by fully reversing its spirit? Whether ordinances can be issued repeatedly on the same subject was another question the court was supposed to answer but hasn’t.

Of the 52 appointees, whose jobs have been secured by the top court’s decision, three have already retired after attaining 65 years of age. The remaining 49 can complete a full six-year tenure given that they don’t attain the retirement age (except in case of the National Human Rights Commission) before completing their full term.

17.78°C Kathmandu

17.78°C Kathmandu