Opinion

From safe motherhood to safe womanhood

I met Dilmaya in 1973 in her village in Gulmi. With a twinkle in her eye, her first words to me were “Pant lauda laj hunna?” In the many intimate chitchats that followed,

Poonam Thapa

I met Dilmaya in 1973 in her village in Gulmi. With a twinkle in her eye, her first words to me were “Pant lauda laj hunna?” In the many intimate chitchats that followed, our laughter was our bond. Dilmaya, married at 13, was 22 years old with three daughters and heavily pregnant. On the last night of my stay, I woke to the terrible sound of women wailing. Dilmaya, “bichari, kasti abhagi” had just died at the hands of a sudeni but the baby girl, “paraya dhan” survived!

I had not known death before, and I cried as if a sister had died, not knowing that my own sister would commit suicide in 1987, as an escape from a highly abusive marriage and the cruelty of Nepali society that often diminishes women’s self-worth. It would be another five years before I understood the term Battered Wife’s Syndrome, which helped me make sense of a sibling’s untimely death.

It is said that on a clear day you can see forever. These two days are my clear days, and one of the biggest influences on my life and profession.

The virtuous cycle

The latter part of the 20th century was a time of great international momentum for women’s health, equality and equity. The 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women has now been ratified by 187 countries, including Nepal. Further ground-breaking international initiatives found resonance in our country’s policy changes and began to address the nexus of rights, women, gender and sexuality in development.

Nepal launched its own National Safe Motherhood Programme (NSMP) in 1996, which has been vital in improving the health status of pregnant women and post-partum mothers. Under the aegis of the landmark Millennium Development Goals, successive social and health sector strategies have provided focus on poverty alleviation, effective governance and revitalisation of systems. The World Social Forum in 2001 gave long overdue recognition to the critical role of national and local non-governmental organisations in development.

This is what I call the Virtuous Cycle of Development: reinforcing changes at the individual, household and community level with international and national policy, and implementation.

Jana Andolan I and II brought about more gender-friendly constitutional and legislative frameworks in Nepal, greater equality and most notably crucial legal protections against gender-based violence. Gender and women’s issues have received increased attention in government, policies, development programmes and budgets.

As a born optimist and a sceptic by experience, I wanted to know what all this means to the lives of Nepali women. The Progress of the Women in Nepal Report, 1995-2015 focuses on three aspects: Violence against women and human rights; resources and capabilities; and voice, agency and leadership. It records some progress towards gender equality and women’s empowerment.

The good news first: Nepal showed great improvement in the Gender Inequality Index (GII), ranking 108th out of 180 countries in 2014, faring better than India, Pakistan and Bangladesh for the first time. Nepal’ GII—a ratio reflecting the disparity in achievement between women and men in reproductive health, empowerment and labour—decreased from 0.658 to 0.479 between 2005 and 2013. This is a result of improved indicators such as Maternal Mortality Ratio of 190 (660 in 1995), the highest percentage of seats held by women in Parliament in the region (29.5 percent), nearly 18 percent of women with a higher secondary degree, and 80 percent of women in the labour force, the last indicator again the highest in the region.

Now the bad news: instead of continuing to drop, as in countries like Sri Lanka and the Maldives, Nepal’s GII rose to 0.489 in 2014 and is expected to worsen in 2017. In 2015, MMR for Nepal was recalculated upward to 258. What is going on?

The missing link

Ask any of the bright technocrats in Kathmandu, and their biggest bogeyman is the bureaucracy of an impractical centralised system, and if I may add, at the hands of resistant men who still make up a large part of the formal workforce. Gender equity remains a distant dream.

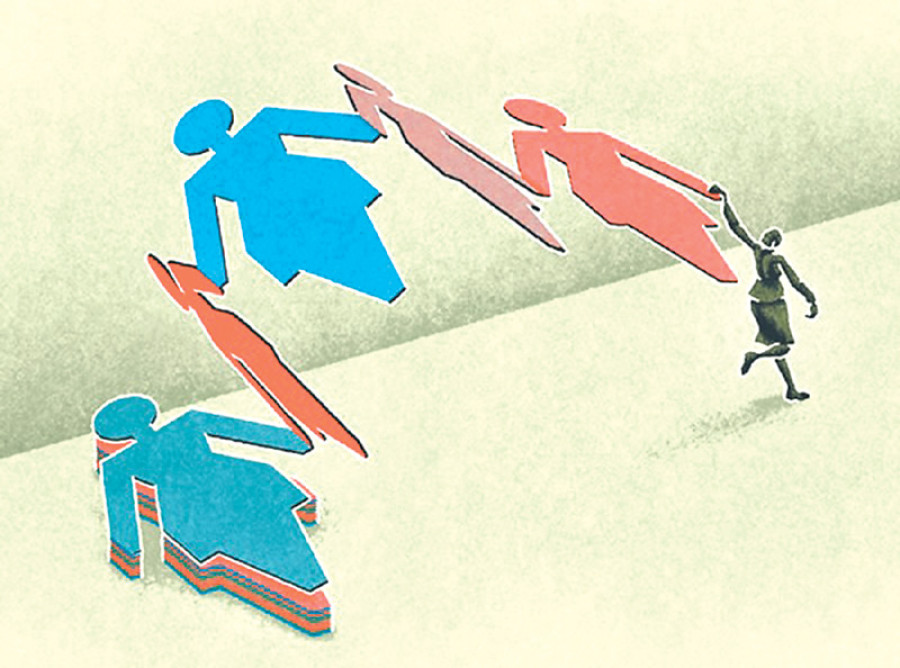

At the 20th anniversary of Safe Motherhood Initiative in 2007, Dr Mahmoud Fatallah, after working for nearly half a century in maternal health and as the founder of the Safe Motherhood Initiative, was asked what he thought was the one prescription a woman needed most to improve her overall health, welfare and well-being. His one-word response: “Power”. He explained that the lack of power from the time a baby girl grows into a woman is very often the biggest risk to her health, which no technology or formal education would overcome in the short-term. Investment in health has increased, but its impact during a woman’s reproductive years (15-49) has been limited as her physical and mental health problems have developed well before these years or continue in later years. The buzz in the room was palpable, for with a masterstroke, the doctor had put the Safe Motherhood Initiative and its programmes squarely within the remit of a life-cycle approach to Safe Womanhood for the former to be successful.

A life cycle approach

The legal, social and cultural slippage we are still seeing in Nepal, despite progress, will always be a risk if women’s health is seen purely through the lens of their reproductive potential. As laudable as the MDGs were, they also relegated women to “mommy-hood”.

Dilmaya sacrificed her life to the will of her mother-in-law and my sister, to the beatings of a husband. For a woman’s life was valuable only if she gave birth to a son. Nepali women even today are not suffering because of motherhood, but because they are born girls who become women.

Nepal has the second highest son preference index in the world, a vicious situation maintained by old discriminatory legal provisions that still remain. In a 2012 study, 90 percent of Nepali men agreed with statements like “A man with only daughters is unfortunate” and “Not having a son reflects bad karma and a lack of moral virtue.” In 2015, related views of superior masculinity were often noted as root causes of abuse and violence against women.

There is a lot of evidence of health risks to girls and women which do not fit the standard definition of violence, but nevertheless have profound effects on their psyche, safety and security. The pace of affirmative action at the national level accelerated under the guidance of the Interim Constitution, and generated many developments including the 16-day campaign and ad hoc programmes about women’s empowerment and action research on masculinity, which I applaud, for every bit counts.

However, as the Sustainable Development Goals take hold, there is an urgent need for a comprehensive and consistent inter-ministerial National Safe Womanhood Initiative—an inclusive Nepali partnership between the government and NGOs that is fully devolved to the federal provinces for optimal implementation. Utilising the current health infrastructure of NSMP and that of education, women and local development, the new Initiative would simultaneously target higher-level health risks to women’s well-being, namely remaining discriminatory laws and high son preference. These two are the root causes of the lower-level health risks, which I consider patriarchy’s toll on Nepali women. They are, to name a few, sex selective abortion, untouchability related to menstruation and childbirth, early marriage, teenage pregnancy, sexual slurs, safety and security of widows, mental health and suicide, accusation of witchcraft, unregulated surrogacy, aged un-protection, and gender and sexual violence in the family and in public space. Zero tolerance and total elimination must be the call of the day. Men, break your deafening silence. Imagine what would Nepal be like if Nepali women are recognised as complete human beings and as equal citizens, and not just as mothers. We deserve it.

Thapa is an international consultant who works on health, gender and community systems strengthening

21.12°C Kathmandu

21.12°C Kathmandu