Opinion

Times of confusion and fusion

Moderation and cultivation of multicultural, multilingual, multiethnic living is what Nepal needs at the moment

Pramod Mishra

It is easier to pay lip-service to building a multicultural, multiethnic, multilingual polity than actually realising it. Most societies contain within them multiple forms of difference at a given time, but most people instinctively feel comfortable with their own kind, and love and appreciate their own cultural artefacts and ways of living. This is human nature; this is also animal nature as a whole. Appreciating other cultures, embracing them or considering them one’s equal does not come easily. It takes much work, education, training, cultivation and consciousness-raising of a specific kind to build a bridge of understanding across the chasm of an instinctual sense of difference as threat or alienation, even though Hindu society has learnt for long to pay lip-service to basudhaiva kutumbakum (the world is one kinship network).

The unseen, unmet world may be one’s kin, but those of a different caste, linguistic group or ethnicity who live next door pose an existential threat to many, hence the need to categorise them as others. It requires sensitivity, empathy and an ability to put oneself in somebody else’s shoes to actually turn the abstract theory into practice. The first two weeks of 2017 have shown that some Nepalis need much training and cultivation to reach that goal, but others have shown hopeful signs. Overall, the situation has not yet turned

irreversible on this score.

Topi day

The year opened in Nepal with a topi day. Men and even women of mostly Khas-Arya ethnic group donned the dhaka topi and marched in the streets to show off their colourful headgear. Their colourful caps with their origins in Dhaka (Bangladesh), Turkey and other places looked really beautiful. I wish they could wear it all year round like many of their fathers and grandfathers.

But this year, I did not see a dhoti procession by the Madhesis like in other years. Every community should take pride in their cuisine, dress, rites and rituals, festivals and way of life. The Maghi festival, celebrated by the Tharu and Magar men and women in equally colourful dresses and jewellery in different places of the country including Kathmandu, was a scene worthy of more than a click.

Nepal has only recently learned to put on display such divergent cultures in public. During Panchayat, students and teachers were required to take part in the procession around town on the king’s birthday or other ‘special’ days. While the latter ceased after the advent of the multiparty system, the former remained a practice. I remember many of my democratic (faculty wing of the Nepali Congress) and progressive (faculty wing of the leftist parties) colleagues would do everything to avoid joining these national day processions around town because of their dissent against the Panchayat system (their political parties were banned). Only the co-opted ones, whose political affiliations were suspect, would don the labeda-suruwal and dhaka topi and travel to various district headquarters to give speeches, praising the king, the regime and then the country. Obviously, there were rewards and punishments associated with the practice.

But now that the Panchayat system has ended and the communists and the NC have occupied centre stage, young men and women of mostly the Khas-Arya community have begun to celebrate January 1st as topi day. Now, if only the children of ex-Panchayat loyalists celebrate the day, it would be natural to do so as a memorial. But if even the children of communists and Congress loyalists celebrate the topi day, then one has to dig deep for meaning. One remembers CPN-UML’s diktat after the second Constituent Assembly (CA) election to its newly elected and nominated members of diverse ethnicities to appear in labeda-suruwal and topi in the CA hall.

Divergent views

It appears that while the Panchayat system by its draconian one-language, one-dress policy protected and preserved their linguistic and sartorial identity, which itself has multiple layers of construction built into it, they could afford to ignore it then for reasons of political difference. With the monarchy gone, and with it dress diktat, too, on its way out, many in the Khas-Arya community feel unprotected and orphaned. That is why many desperately seek some protection—be it of the topi or even of king Prithvi Narayan Shah—so they could feel the ground beneath their feet still intact.

This year again, more than in others, an increasing number of people of the Khas-Arya community, including those from the NC and the UML, combined their anger with that of the veterans of the old regime to demand that the government celebrate king Prithvi’s birthday by making it a holiday like it was before 2006. The Cabinet discussed it until the evening before, but could not go forward, disappointing and even enraging some of the founder’s devotees.

While the ‘other’ of the Topi day are the Madhesis who do not identify with the sartorial item and consider it as an imposition on them at the expense of their own dhoti-kurta-gamcha, which many young men no longer wear, the ‘other’ of the Prithvi day are the Madhesis as well as the Janajatis who consider Prithvi a warlord who by force or trick conquered them and annexed their territories, and his descendants and lieutenants forced them and their culture to survive at the margins. That is why while many Khas-Arya folk of both the old and the new regime celebrated Prithvi’s birthday, many inhabitants of Kirtipur demonstrated (some by spitting) to commemorate their humiliation of nose-slicing over two centuries ago.

(In)tractable problem

The acts of even women wearing men’s topi to assert their sartorial nationalism, others fuming over the government not celebrating king Prithvi’s birthday and yet others spitting show a lack of moderation among many Nepalis in this transitional period. The women donning men’s cap show that they could be as aggressive nationalists as men, and equal to their men folk who had deemed them inferior. But this is an unproductive way to demonstrate equality because Nepal is in transition. Things are in a flux. Old certainties have disappeared; new guarantees are yet to appear. Women cannot be their men’s equal by wearing a topi. Real equality will come from legal, social and economic changes.

Those who never had their dress and language recognised, and their ethnic icons acknowledged and celebrated, equally fear that they will again be denied their due. By spitting, they, too, have shown extreme reaction. In this period of transition, there needs to be a balance between the mind and the heart, between thoughts and emotions. Above all, moderation and cultivation of multicultural, multilingual, multiethnic living is what Nepal needs right now. Anybody who shouts too much about their topi or dhoti (or about their anything) ought to be either laughed at or considered suspect.

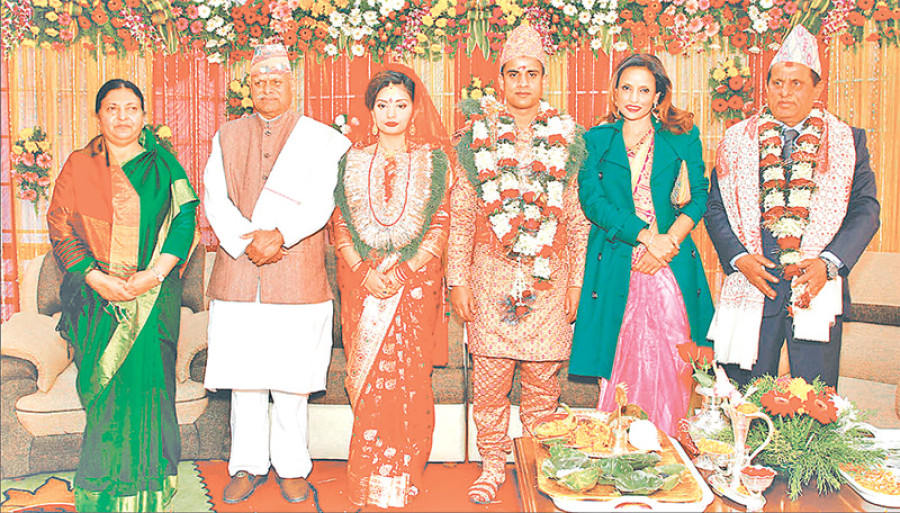

And this brings me to my last point: hope. This week also saw the multiethnic, multilingual, inter-caste wedding of President Bidya Bhandari’s daughter Nisha Kusum to Avishekh Yadav. Even now a so-called upper caste Madhesi mother and father will have a heart attack like situation if their daughter desired to marry a Yadav boy. But President Bhandari has shown that she not only broke the backwardness of Nepal’s feudal tradition symbolised in the royal palace (the cause of the royal massacre of 2001 was a family stigma related to purity) but also the orthodox traditionalism of caste Madhesis. Such an example at the highest level of Nepal’s power structure shows that Nepal’s ethnic problems are not intractable. A little bit of education, a little bit of cultivation and more meaningful reciprocal dialogue between and among divergent groups have the potential to resolve even the seemingly intractable problems. This is really a time of confusion but also of hope.

9.83°C Kathmandu

9.83°C Kathmandu