Opinion

Not working

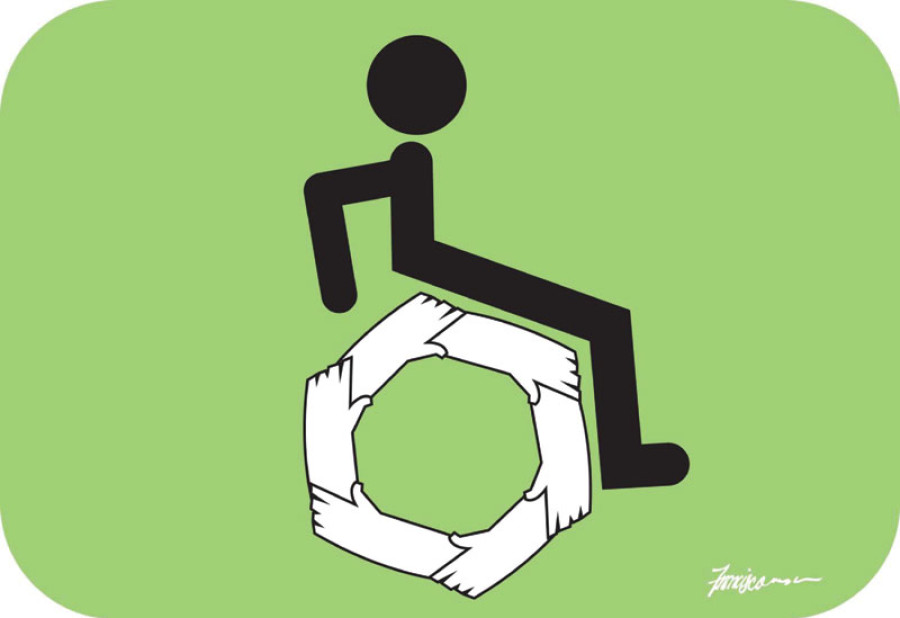

Many financial cooperatives in Nepal are not open for business for vulnerable and disadvantaged youths

Simone Galimberti

In recent months, quite a few bills related to the economy have been passed by Parliament, showing a renascent interest of the government in harnessing the business potential of the country. Last among them, the Industrial Enterprise Act has been welcomed by both the Federation of Nepali Chambers of Commerce and Industry and the Confederation of Nepali Industries, the two major associations of entrepreneurs and business leaders. The government has also recently tabled the Cooperative Bill that is aimed at better regulating a sector that had gone astray since long with many cases of mismanagement and misappropriation of resources.

In spite of everything, we should not forget the roots of the cooperative movement. Robert Owen and William Kin, the latter the founding editor of the magazine The Co-operator whose first edition was published in the UK in 1828, felt the need to create financial institutions run by the members and able to fill the gaps faced by workers in the midst of the industrial revolution. Therefore, cooperatives by default should be economic entities strongly led by a social mission, something not too different, at least in substance, from the more recent phenomena of social entrepreneurship and social business. Yet, most of the co-operatives in Nepal are unfortunately not open for business for vulnerable and disadvantaged youths.

Left behind

The business leaders of the country should be able to seize the momentum offered by the new legislative framework and truly leverage it not only for their own good but also for expanding the limited and often exclusionary economic opportunities for the people. Business leaders should do much more to make their companies more open and inclusive.

It might be not a coincidence that I never heard of or met any business leaders representing vulnerable groups like the Dalits or persons living with disabilities, showing that a vast gap still prevails in terms of access to economic opportunities.

On October 12, the International Labour Office (ILO) Global Business and Disability Network will host its global summit in Geneva where many multinationals will sign the Business Charter on Disability that offers a framework for inclusive business practices, specifically targeting persons with disabilities.

Here we are talking about big multinationals that have the resources, means and skills to reasonably accommodate the needs of persons with disabilities. But interestingly, closer to home, Bangladesh is moving ahead on its quest to make its industries more inclusive and accessible. Last February, the ILO and the Bangladesh Employers’ Federation convened a workshop to locally replicate a network promoting inclusive practices.

Moreover, the Ministry of Education in Bangladesh, as part of the Bangladesh Disability Welfare Act (2011) and the National Skills Development Policy (2011), enforced a 5 percent quota for persons living with disabilities to access technical and vocational institutions throughout the country. Nepal should also make efforts to promote policies or practices that can gradually make the national economy more open for vulnerable groups.

Way forward

At the moment, many industries in Nepal are being led by persons who have studied overseas and know firsthand about the inclusive practices in countries like Australia and the US. While we should all push for a new disability Act, the younger generations who are taking over many of the business houses in the country and who are continuously exposed to the global world and international best practices, should do some introspection and think if they can also play a role in creating a more inclusive economy where everybody, regardless of their vulnerabilities, can have a shot.

After all, organisations like Rotary, Lions and Round Table, whose members are mostly in key positions within the private sector, could play an important role in starting a national conversation and doing away with some outdated mindsets according to which a person with disability is not suitable to work.

They should not do this as a part of their charity or corporate social responsibility but rather because excluding big portions of the population from the national economy will, in the long run, affect them adversely.

Interestingly, the country saw an upsurge in the number of cottage, small and medium enterprises in the recent decade. There are even special funds to incentivise more women to become entrepreneurs. Unfortunately, there has not been a national campaign to promote such actions, and often the resources available are either unspent or misused. How many youths from disadvantaged or vulnerable groups have tried to access the Youth and Small Entrepreneur Self Employment Fund? My guess is that too few, if any, benefited from it.

The country will be more economically vibrant and inclusive only if we work at multiple levels, for example, with more provisions and policies enacted by the state, by starting new internship and traineeship opportunities offered by the major business houses and by expanding the entrepreneurship space for those youths unfairly excluded till now. Small but incremental steps at the beginning can be scaled up to make Nepal’s economy more vibrant.

Galimberti is the Co-Founder of ENGAGE and Editor of Sharing4Good

14.24°C Kathmandu

14.24°C Kathmandu