Opinion

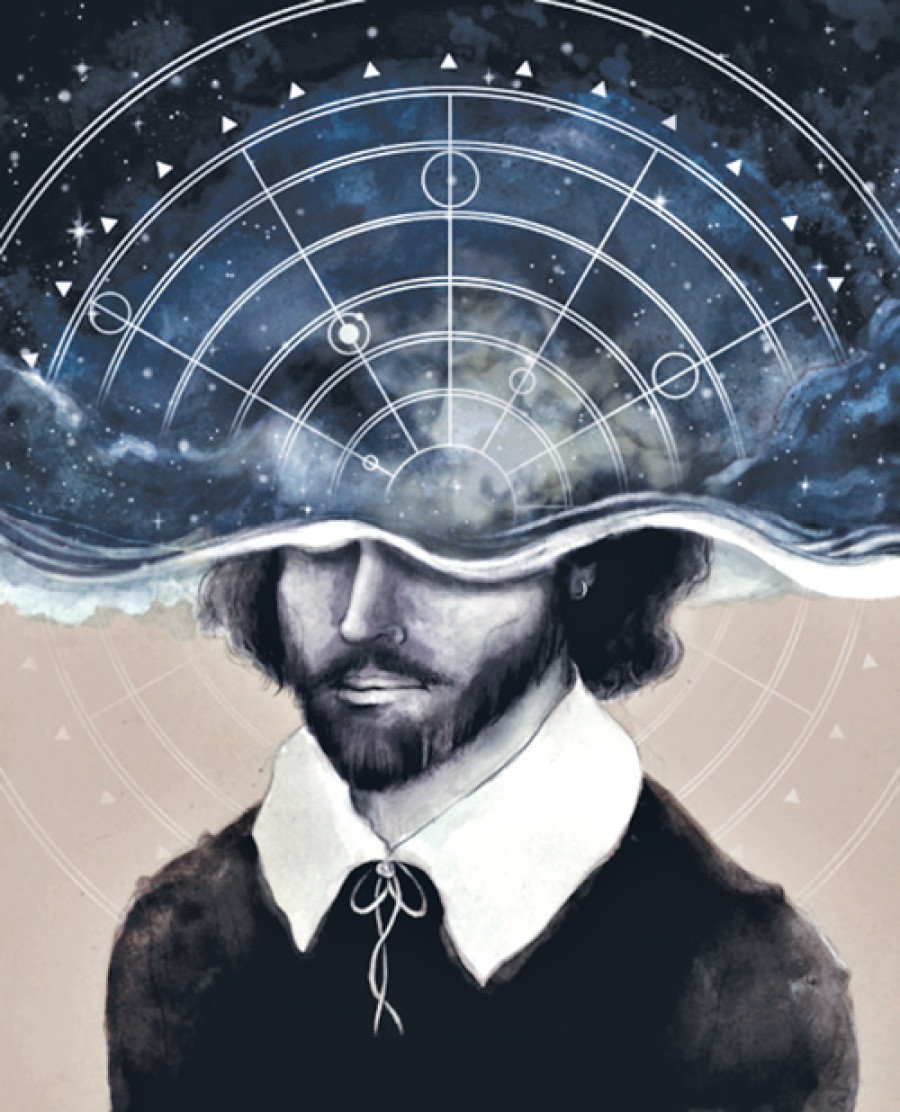

Shakespeare phenomenon

People continue to use the Bard’s works as an inexhaustible source of creative inspiration

I was invited to talk about William Shakespeare and his place in our literary education, especially in the context of the English literature studies.As this year marks the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death, the programme was especially designed to theorise a few outstanding questions of comparative literature. An important topic of discussion was the nature of the Bard’s influence, if any, on Nepali writers, especially on the writings of the Nepali theatre maestro Balakrishna Sama (1902-1981). I attempted to theorise the nature of the influence by putting English literature, literary influence and literary canons in a discursive context. But, more importantly, that colloquium triggered my own memories and perceptions about Shakespeare, which I am going to discuss in this short essay.

The world has become what it is today since the times of Shakespeare in all the spheres and pursuits of life—epistemology, aesthetics, science and politics. Shakespeare is still quoted by people in different moments of inspirations, including a monk waking up from his meditation, English teachers from Nepal and South Asia, writers and speakers worldwide with the gift of the gab who would cite either the gist or the aphorisms from Shakespeare’s plays and poetry.

Guerrillas and Sadhus

As someone who has spent over four decades of life teaching what is called “English literature”, meaning Shakespeare’s literature, it is very natural for me to remember the Bard who has become the very atmosphere of my mind. For me, to try to find something to say about Shakespeare is to speak the language of silence; to try to locate any critical information about him is to expose myself to mini-cyclones of creative criticisms; to dissociate myself from this English male white writer as a postcolonial theory savvy is to draw myself still nearer to the tempest of his poetry.

I began my English teaching career with a slim volume entitled “Stories from Shakespeare” that covered the outlines of all his tragedies, comedies and history plays. I taught that at Patan College to science and arts students. One of the students was Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’, the present Nepali prime minister. Years later, Bijaya Pandey asked me on his popular Nepal TV show, “What did you teach Prachanda?” Knowing what Pandey was aiming at, I answered, “I taught him tragedy, comedy and history; he is doing all three now.” Indeed, that was a minuscule moment of English teaching by using Shakespeare.

I believe that any political challenges, revolutions and moments of peace, crisis and periods of bigotry and hate politics, which is unfortunately beginning to appear in the Western world, can find the Bard’s plays inspiring and correct the wrong path by using his plays as eloquent poetic metaphors of life and human narratives. Plays or theatre can always give you solace, salvation and tongues to speak.

Guerrillas and Sadhus alike quote Shakespeare. An example is in order. Stanley Stewart in his posting of April 25, 2016 on the BBC under the title “The holy sadhu who loves Shakespeare” reports this moment of epiphany upon meeting the old Sadhu in India,—“He giggled into his beard. ‘Through all our lives, desire pursues us like ‘fell and cruel hounds’, he quoted.’ A quote from the Ramayana? I asked, referring to the great Hindu epic. ‘Shakespeare,’ he said. ‘Twelfth Night’.” Such examples showing the enormity of Shakespeare’s influence abound.

Among the Shakespearean critics whose works have tremendously influenced me are G Wilson Knight with his Wheel of Fire, and Eric Bentley who turned 100 a few days ago on September 14. When I met Bentley at the 50th World Congress of the International Association of Theatre Critics (IATC) in Seoul in October 2006, I had the opportunity to ask him if Shakespearean criticism was still valid. He said it is more valid than ever before because criticism is the only heuristic way to truly understand the Bard’s works.

Accepting the first Thalia prize given to him by the IATC, Bentley said that the function of theatre criticism is to save it from what he called the falsity of “devastating one-liner” that the newspapers promote by wanting their drama critics to be “taken more seriously, as if they were experts to be envied.” Except for a year or two of the Puritan England when “God trumped Shakespeare”, the Bard never ceased to shine in the non-communist and communist worlds alike. I was amazed to see the performance of Macbeth in the Chinese opera style.

The English language

Another remarkable matter is that Shakespeare links us to other countries of South Asia. We glibly use Shakespeare’s plays in English education and literature. Though using Shakespeare to teach the English language is not appropriate, it nevertheless became part of the curricula of the English language pedagogy, but, I guess, as a symbolic factor. India uses English as a second language, whereas we use it as a foreign language. That makes a world of difference. India produces writers in English, naturally. In Nepal those who write in English tend to believe they are better writers than those who write in native tongues, which is not a truism. The underlying cause of this attitude is that English has remained a foreign language for us, something that is learned and used in limited domains. The concept of writing ‘good English’ therefore dominates our psyche. If you see some foreign English tomes labelled literary collections, with the exception of some like Michael Hutt’s Himalayan Voices: An Introduction to Modern Nepali Literature (1991), a body of translated Nepali literary works, they are principally guided by sampling the “good English” rather than freely and confidently written English with near-native proficiency.

Interestingly, the Bard binds us all in this region. People do not use his plays to teach language anymore, but they use him as an inexhaustible source of creative inspiration. A certain ambivalence works here. Shakespeare is viewed as an English writer par excellence, which indeed he is. But he is also viewed as everybody’s writer without frontiers. Such ambivalence is the example of creative pragmatism, which is the soul of world literature.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)